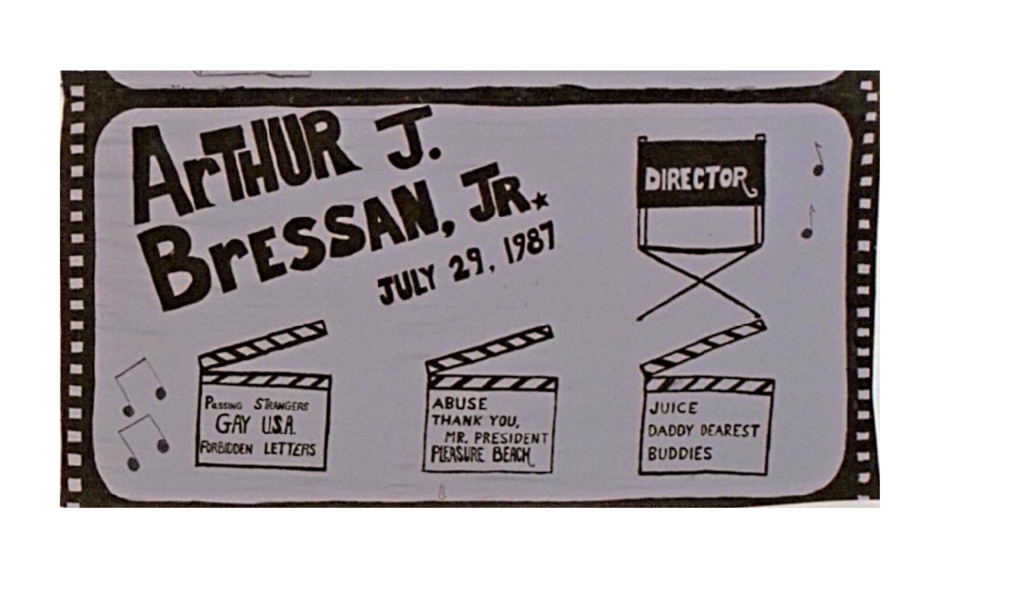

He died at Garden Sullivan Hospital in San Francisco.

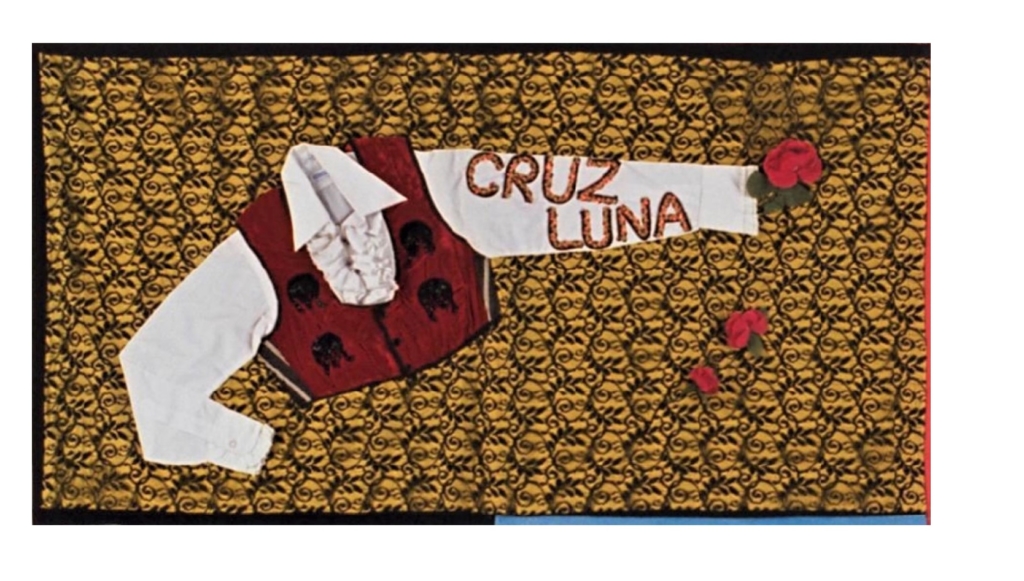

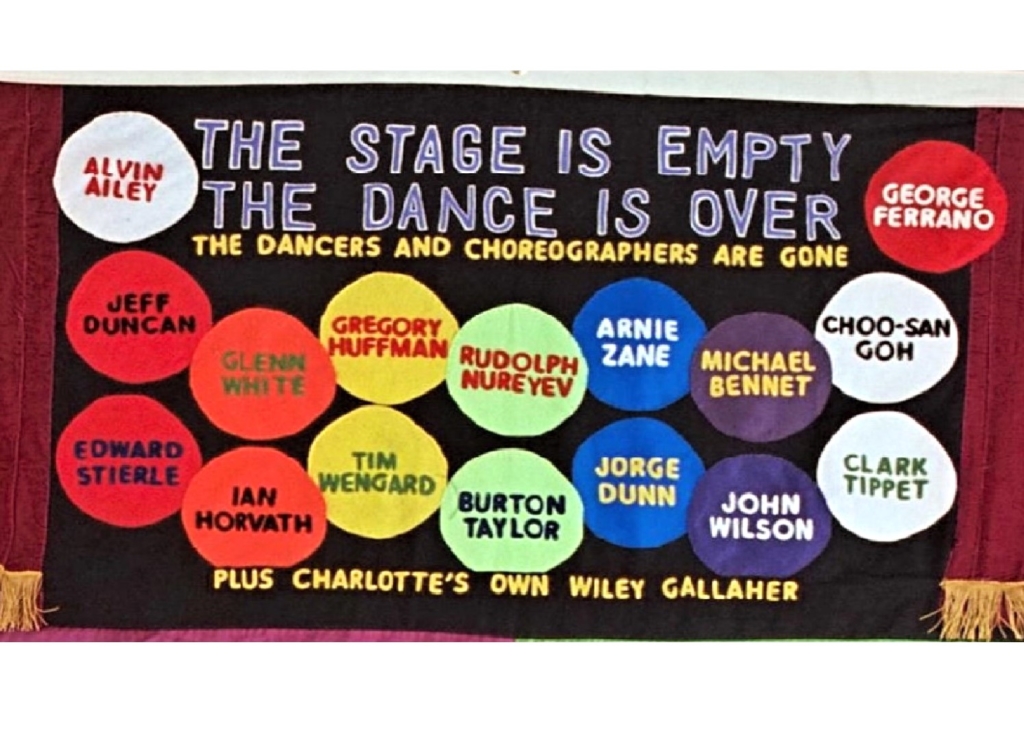

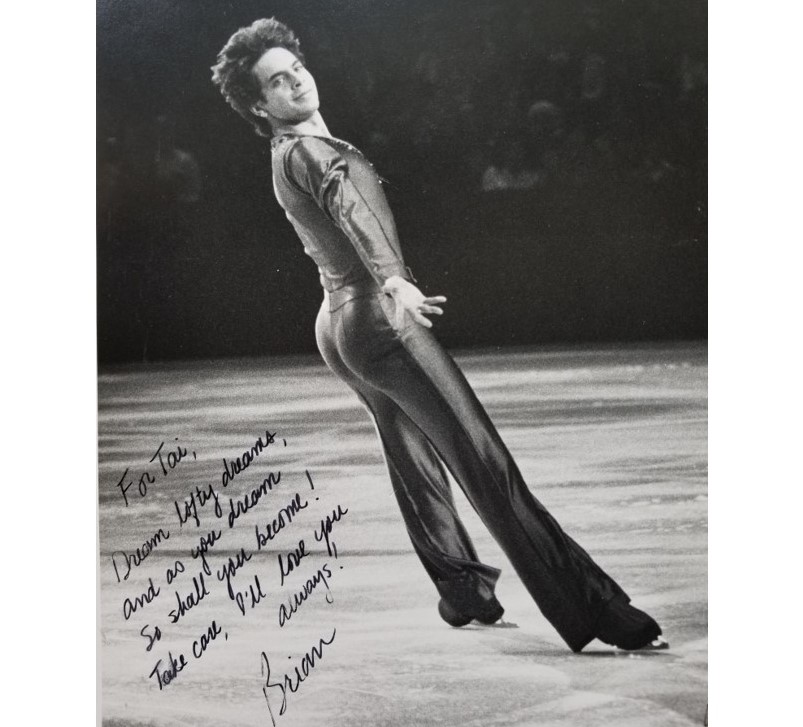

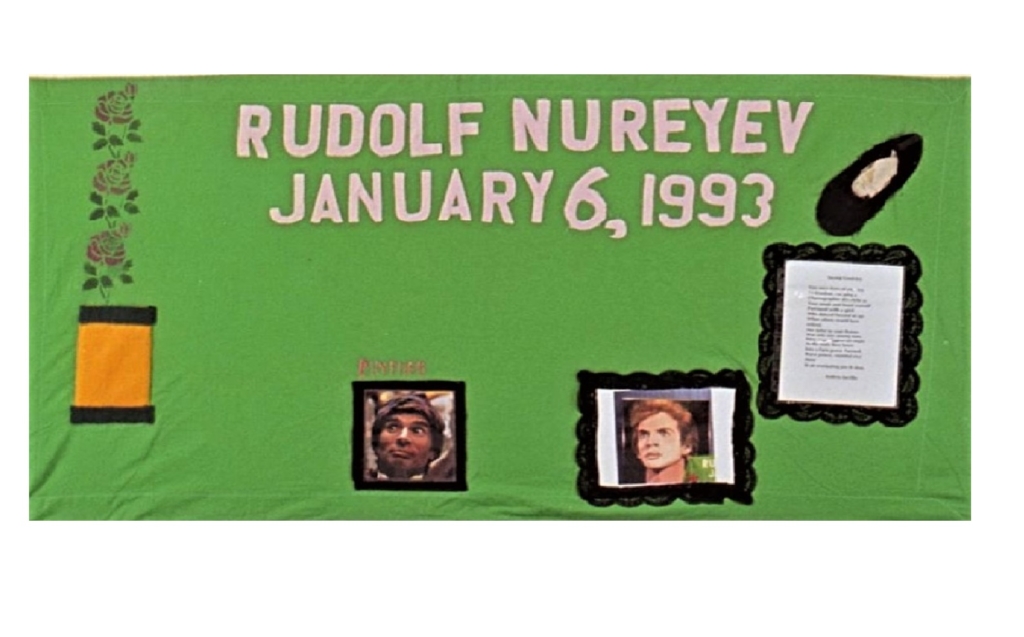

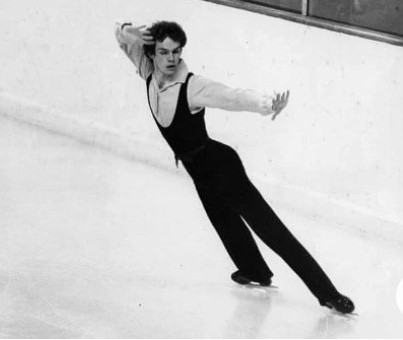

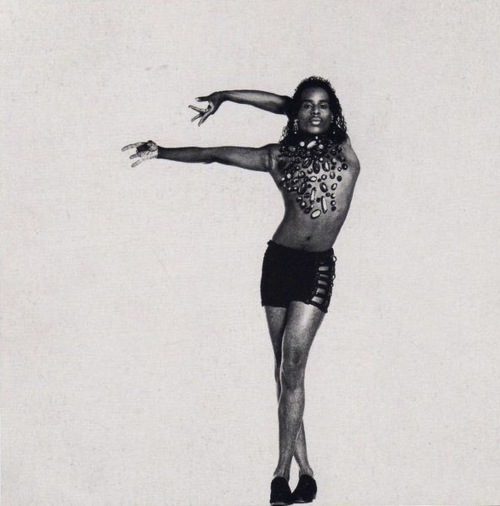

Luna is memorialized in the project Dancers We Lost: Honoring Performers Lost to HIV/AIDS.

* * * * * * * *

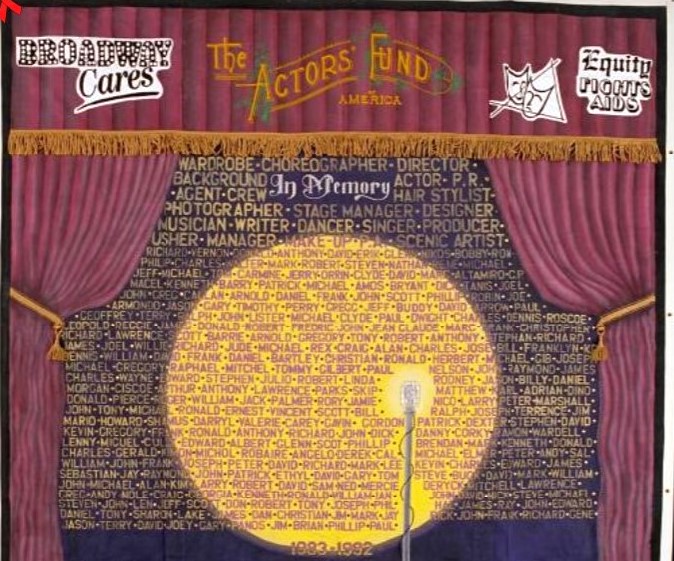

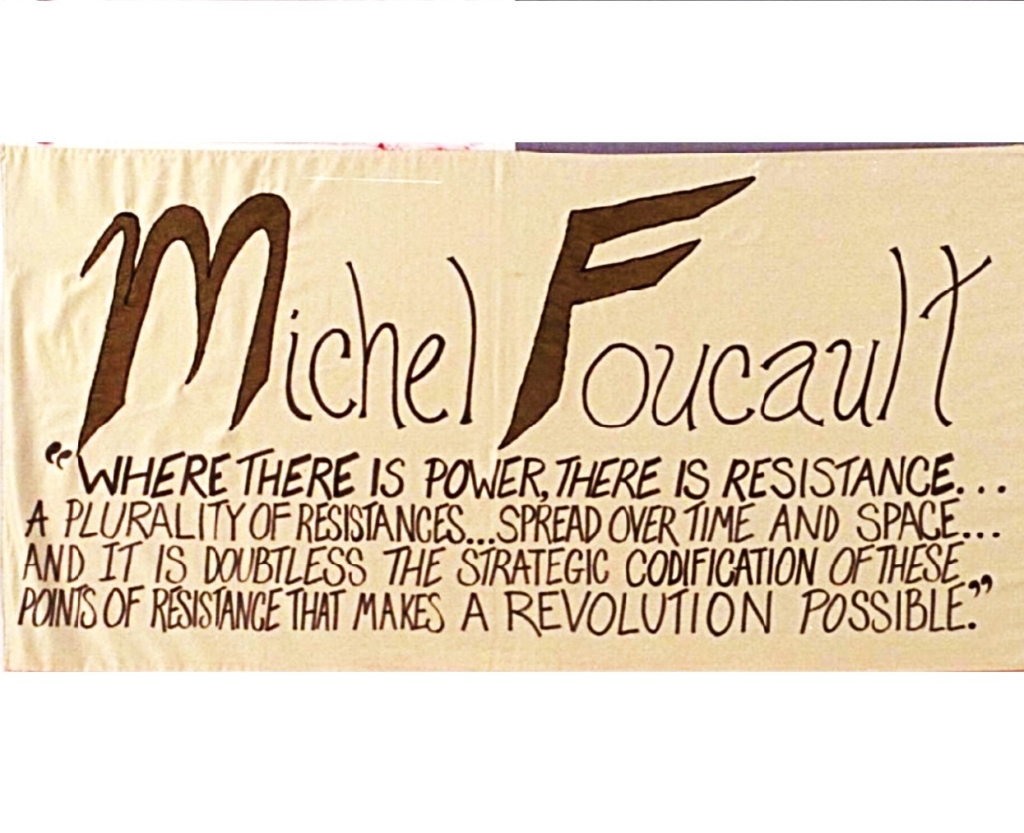

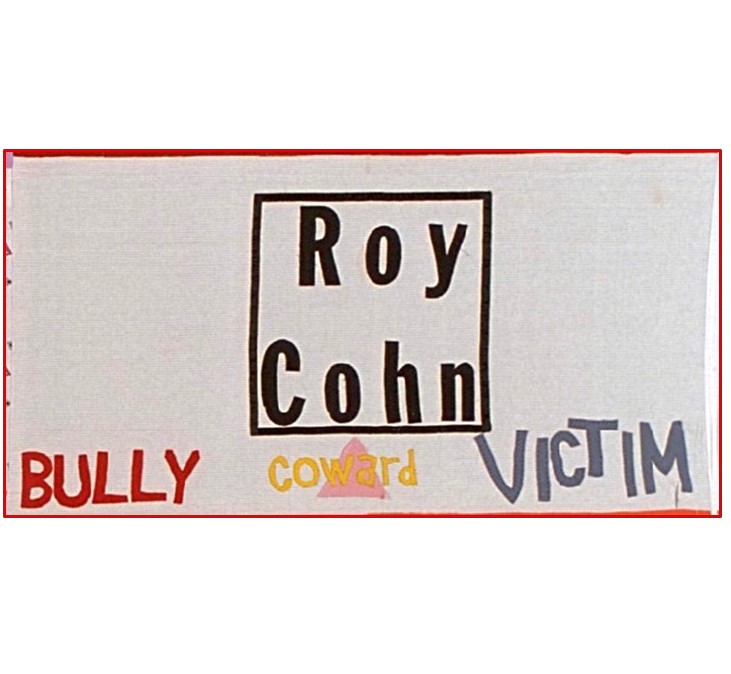

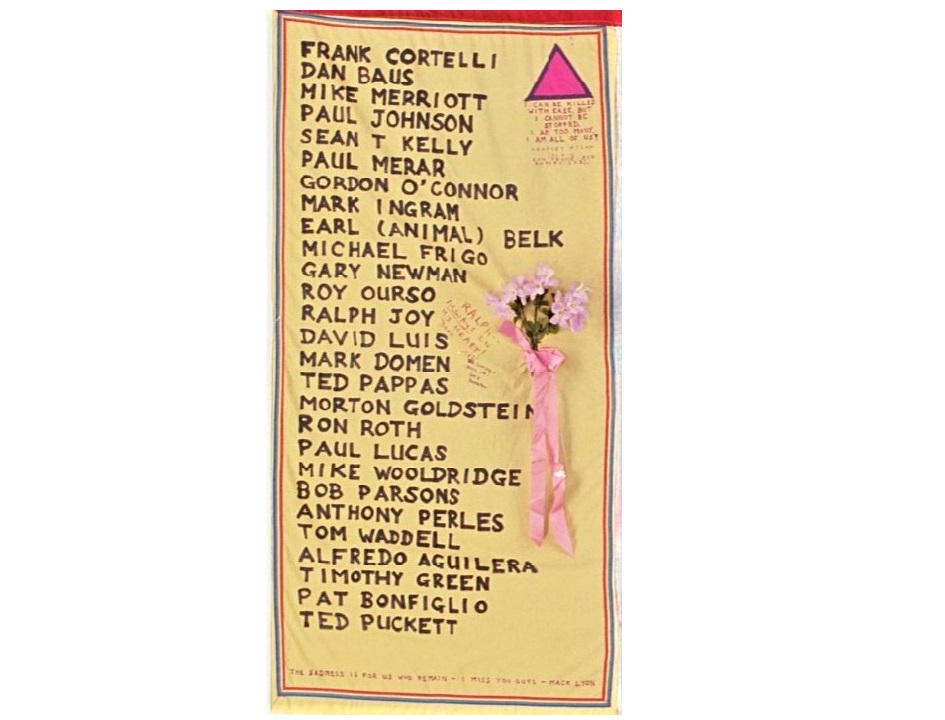

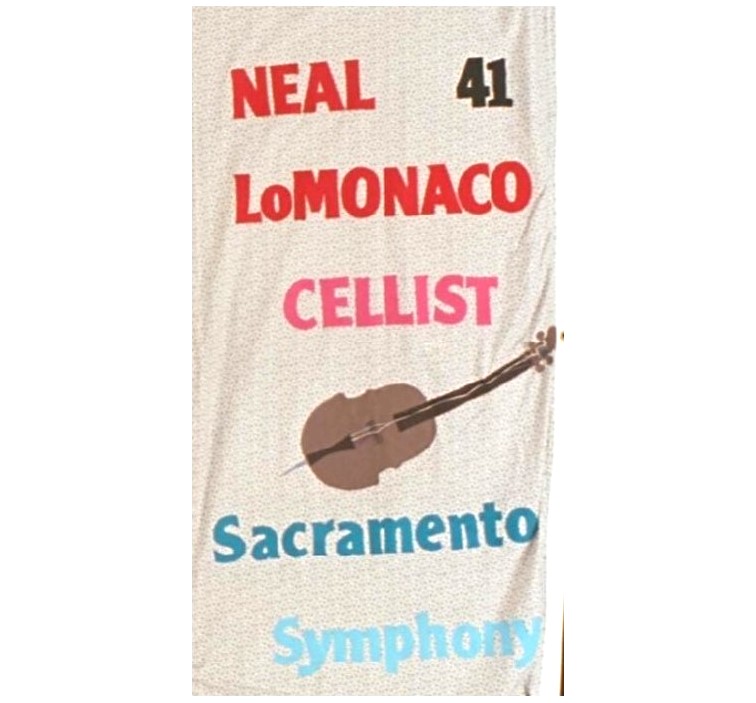

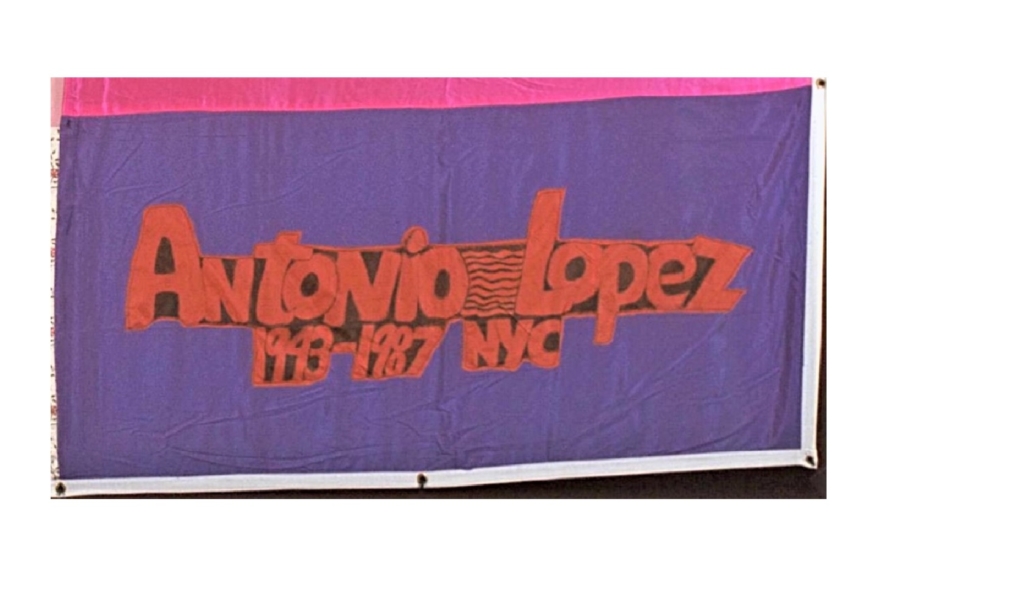

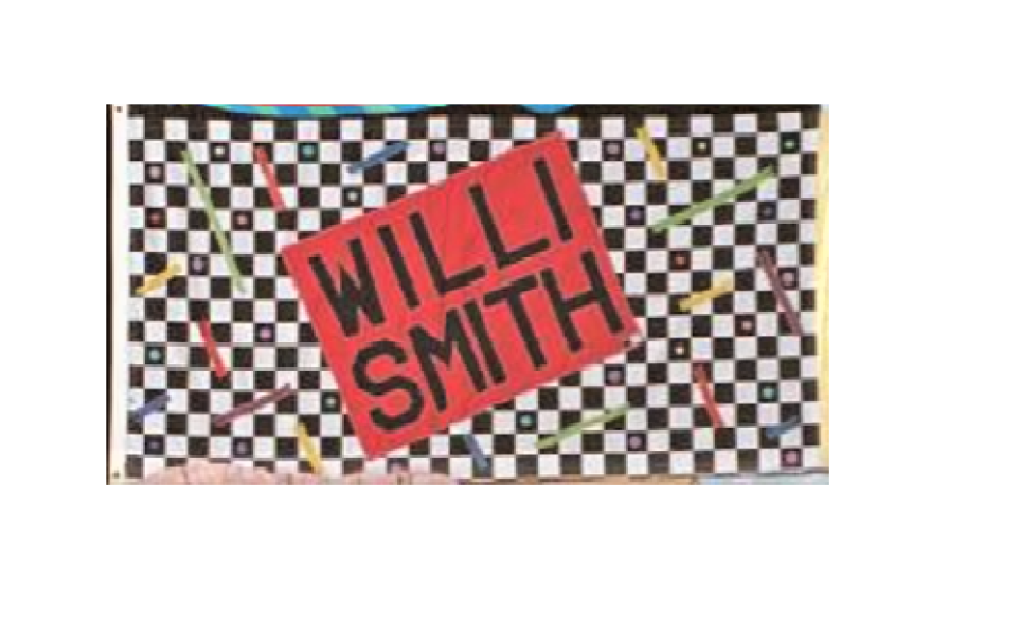

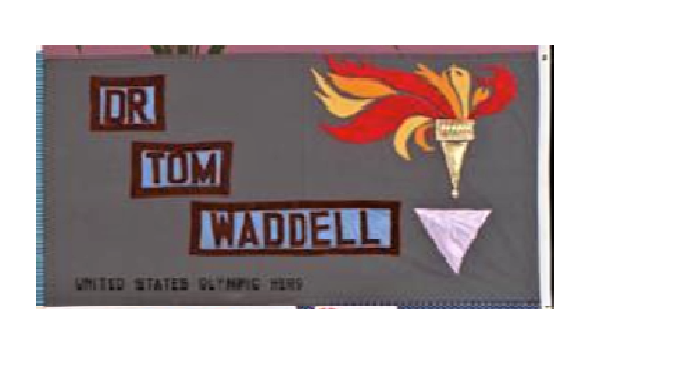

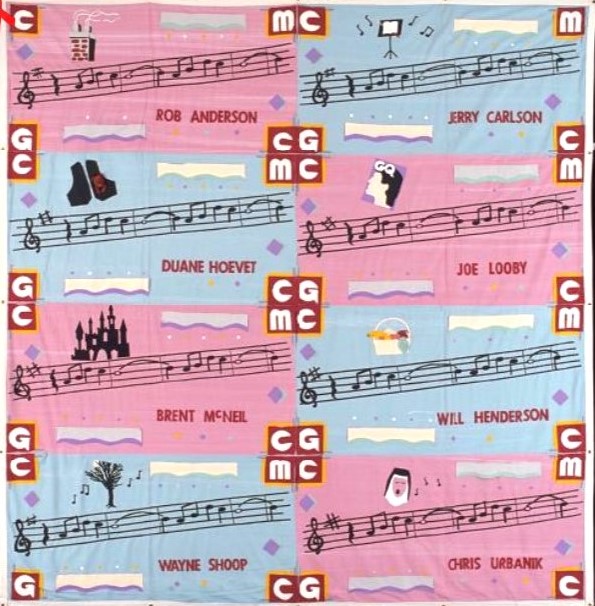

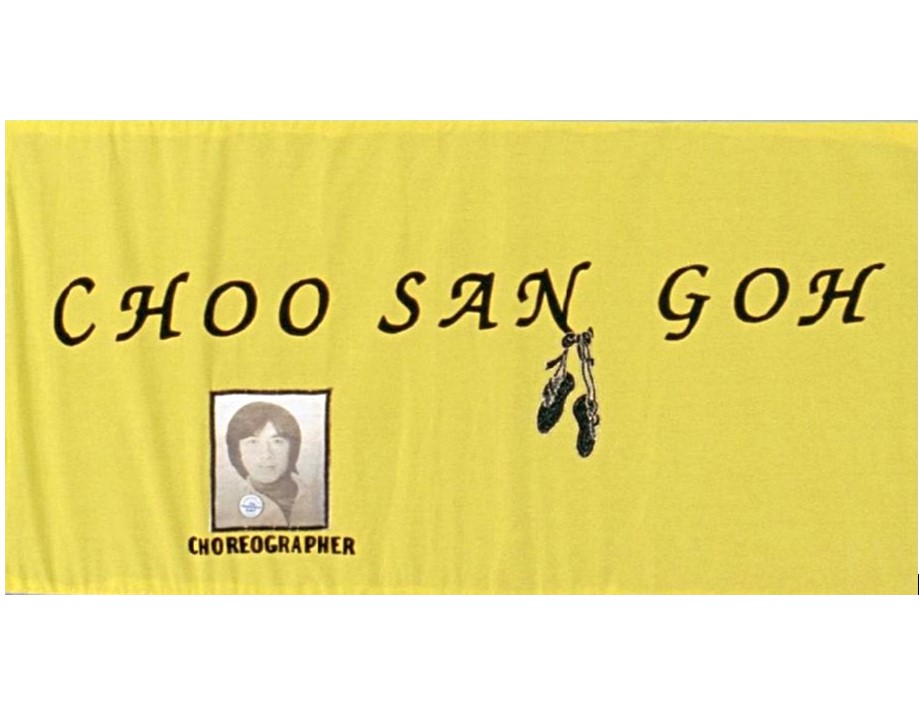

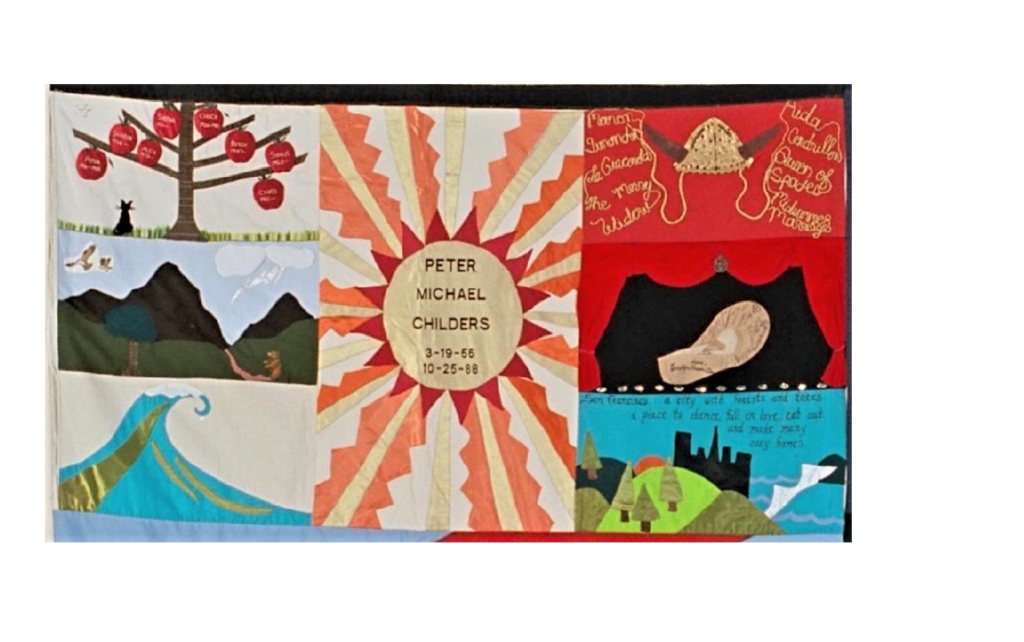

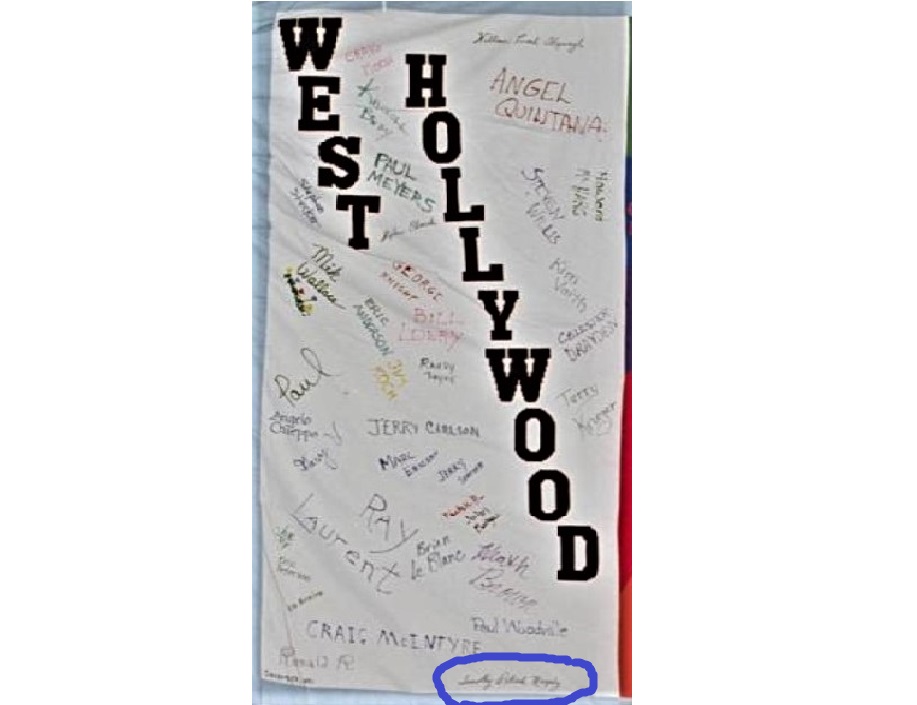

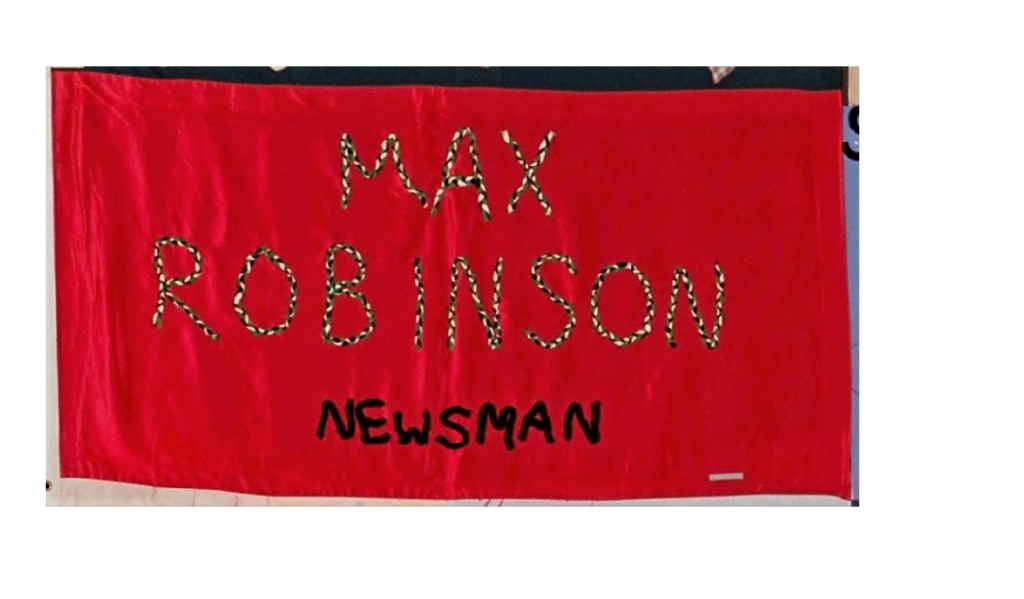

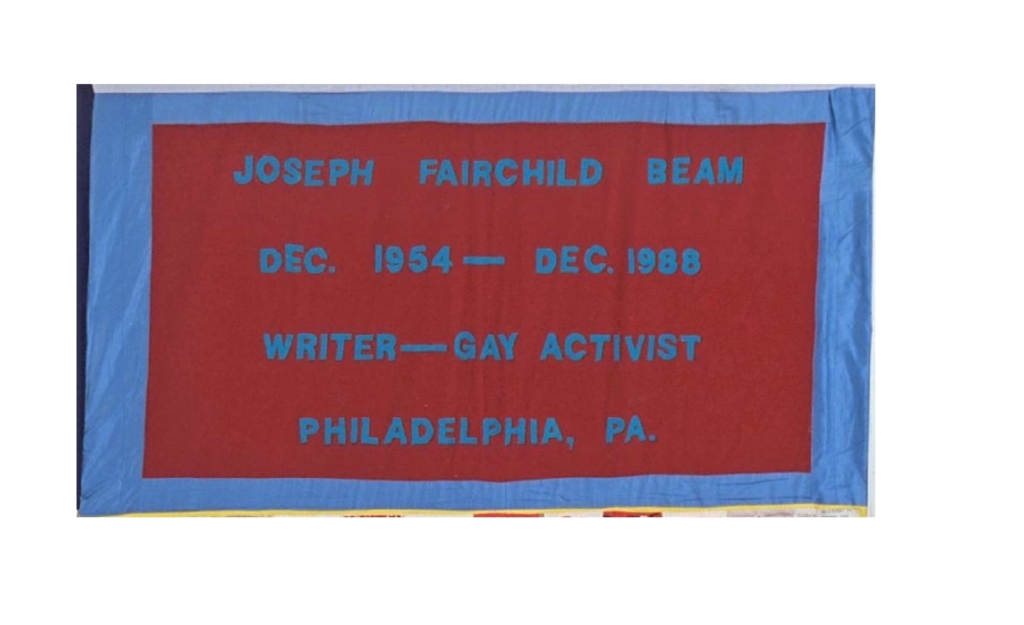

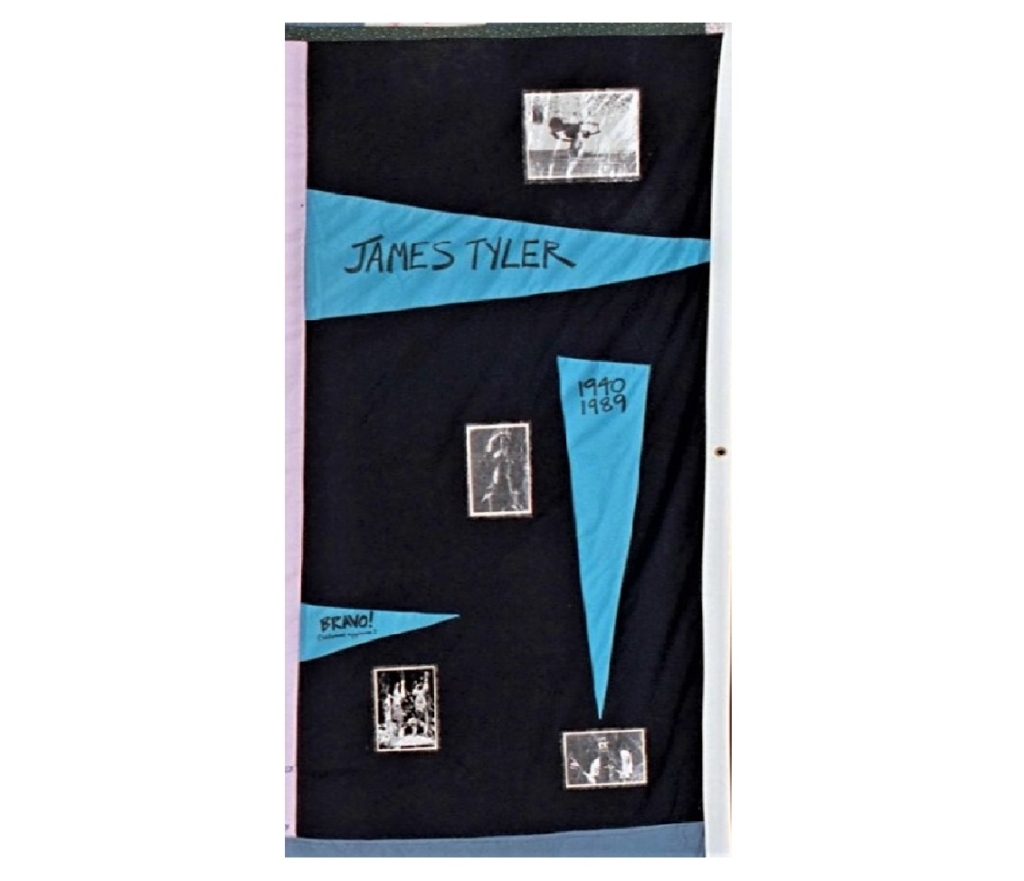

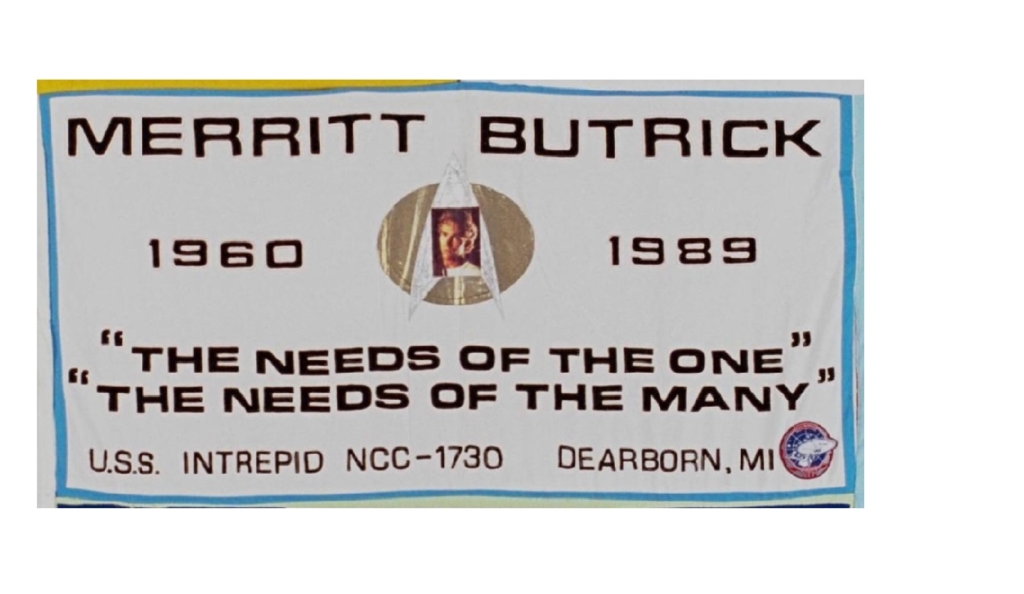

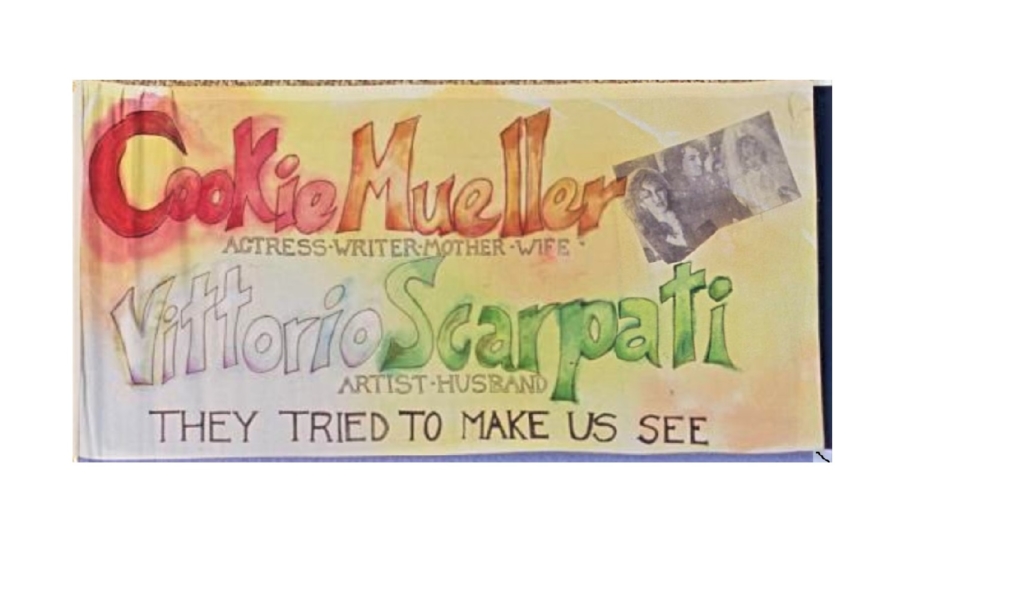

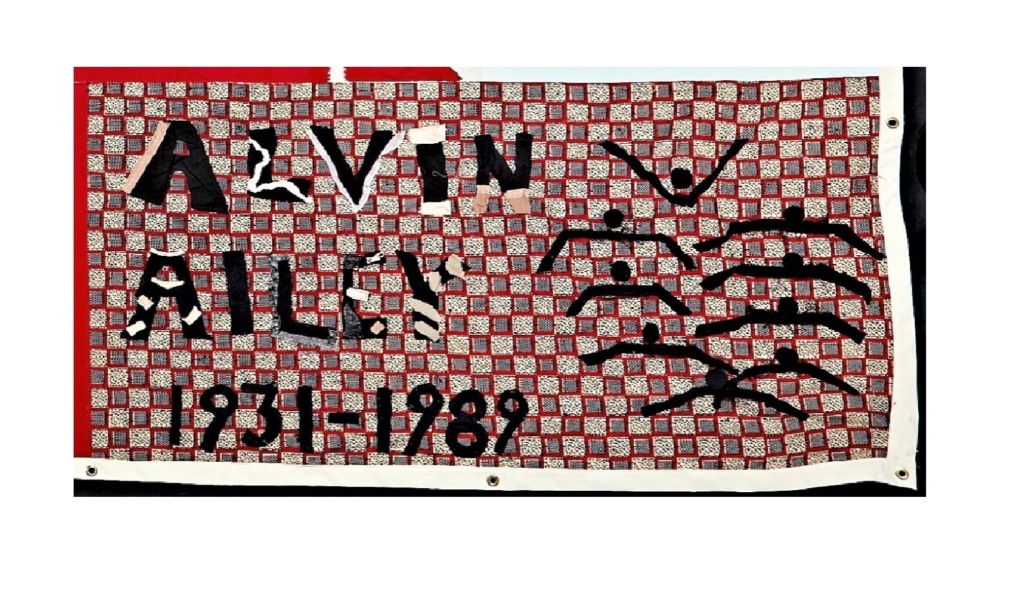

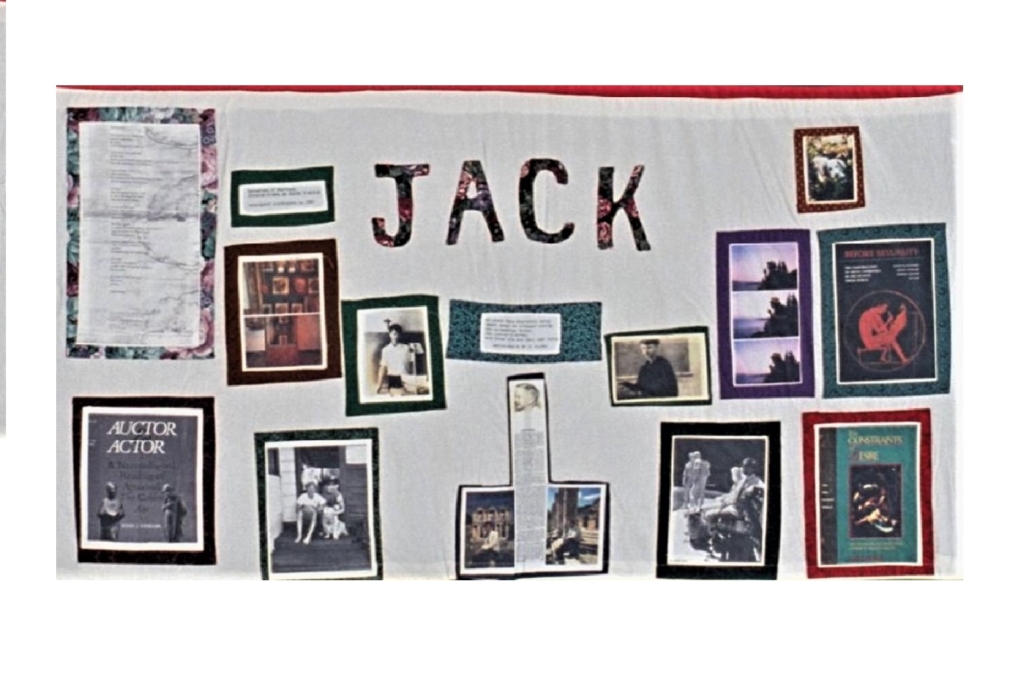

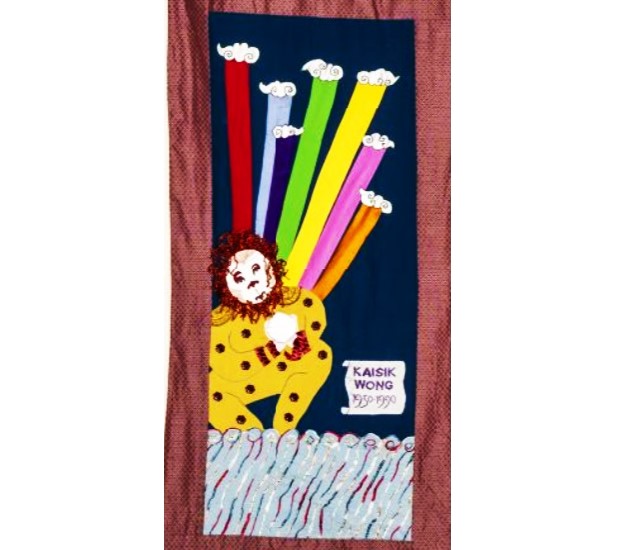

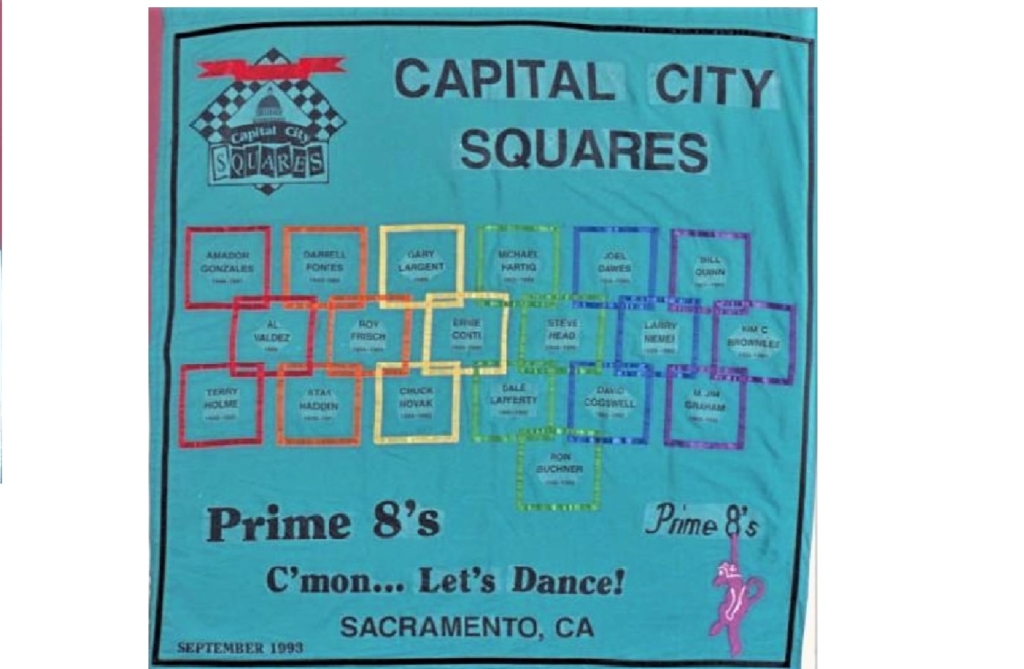

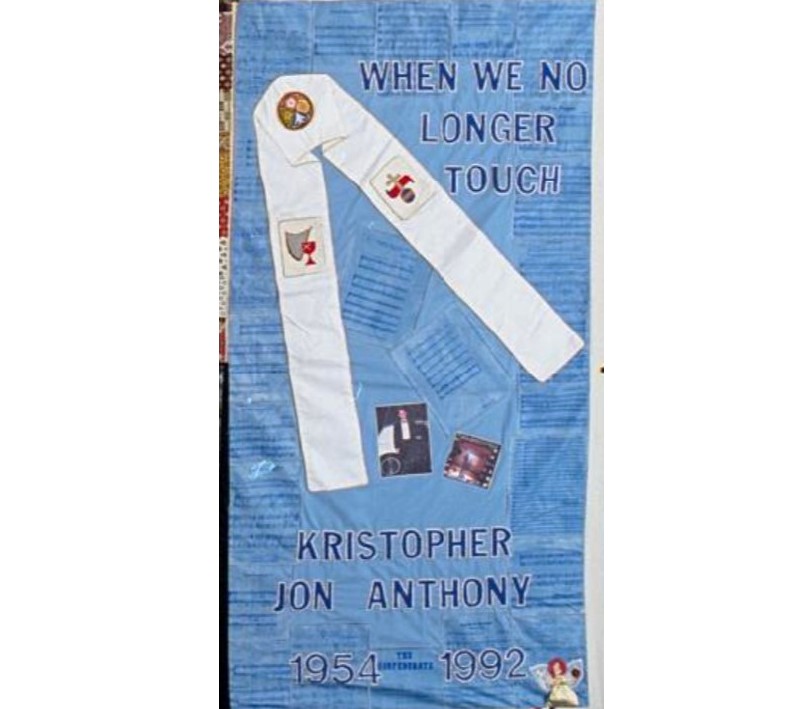

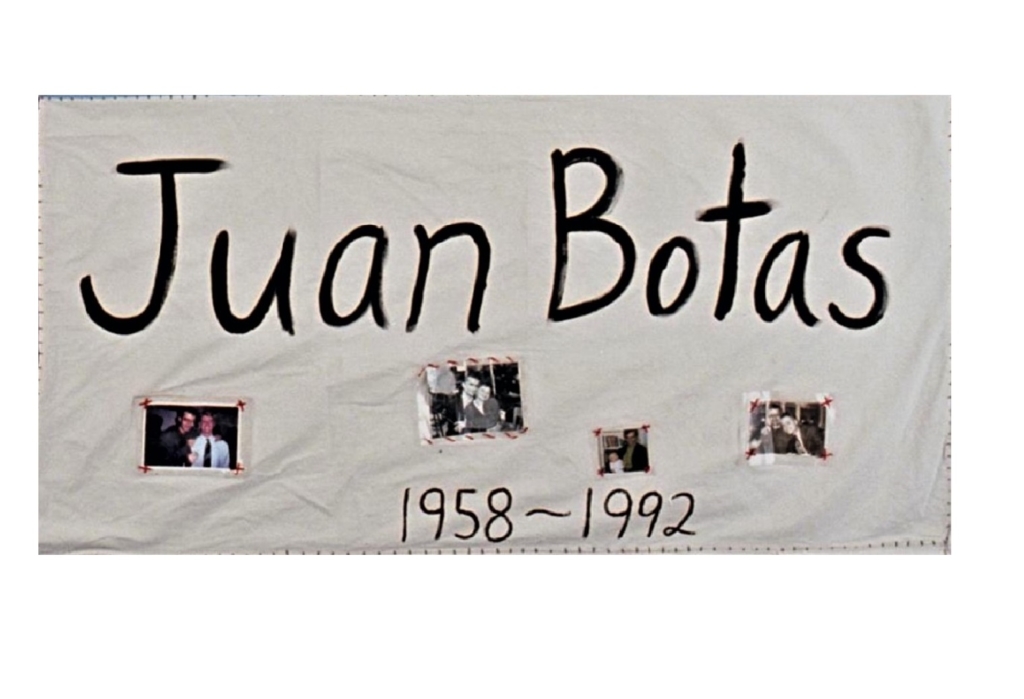

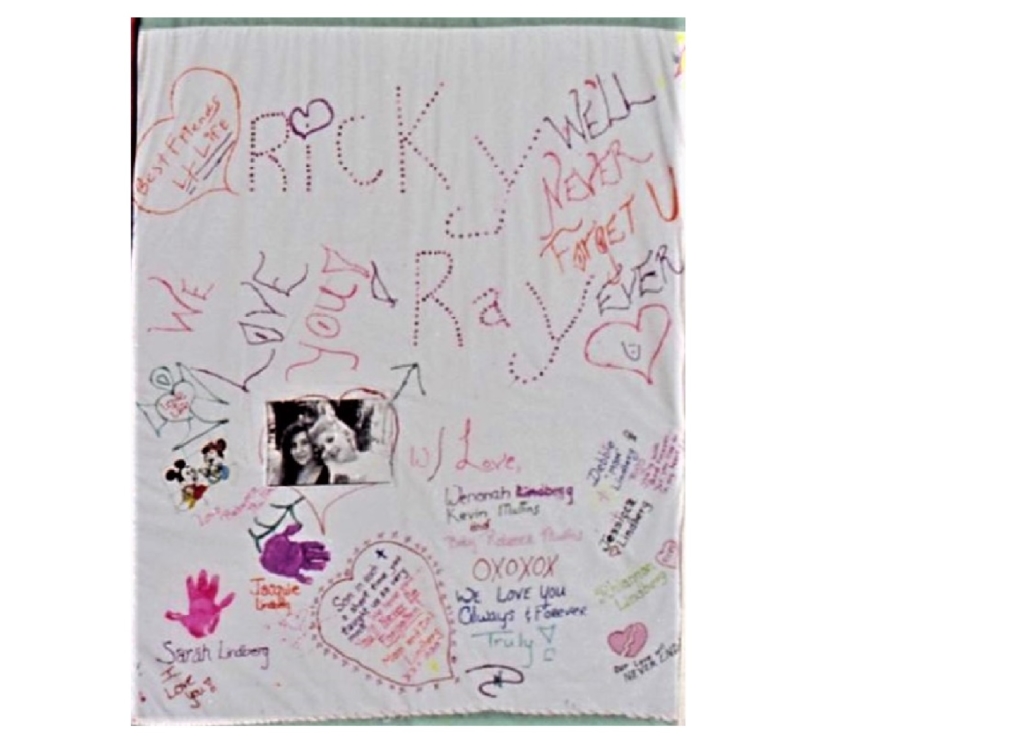

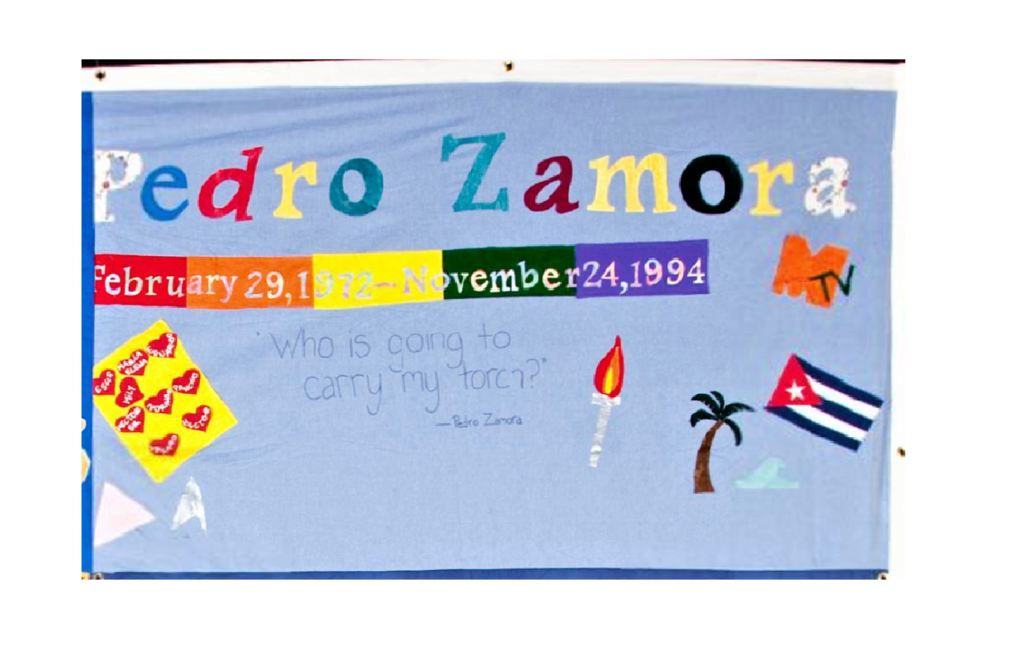

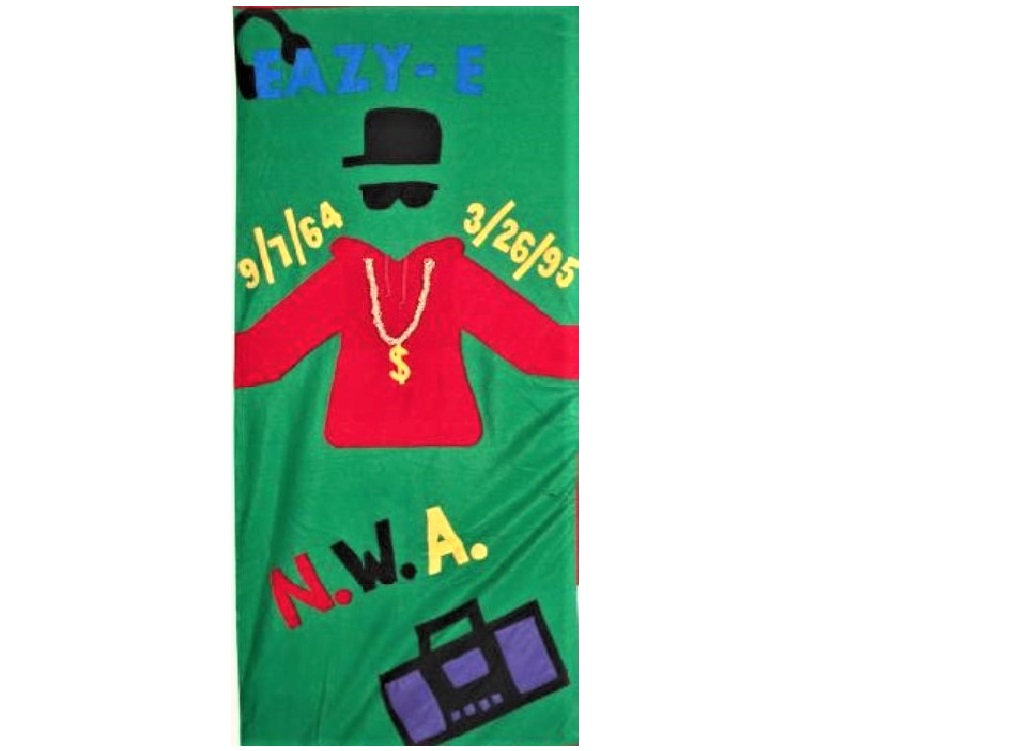

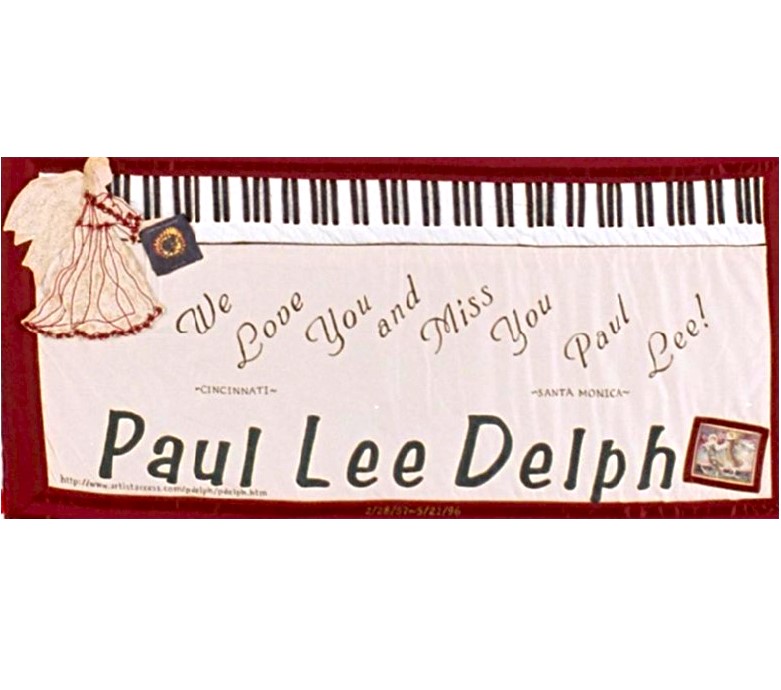

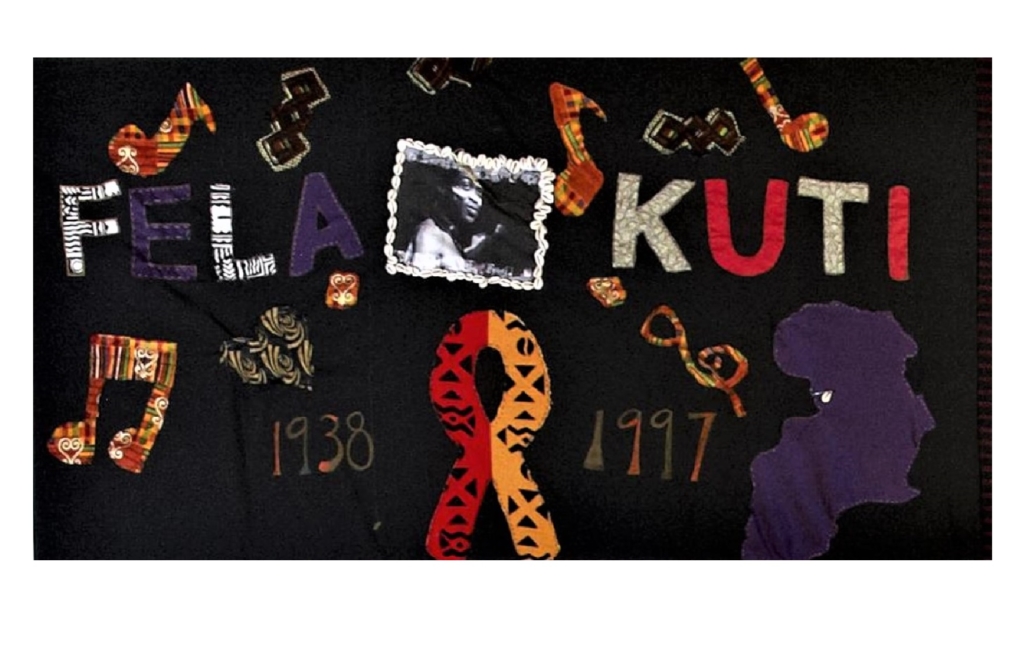

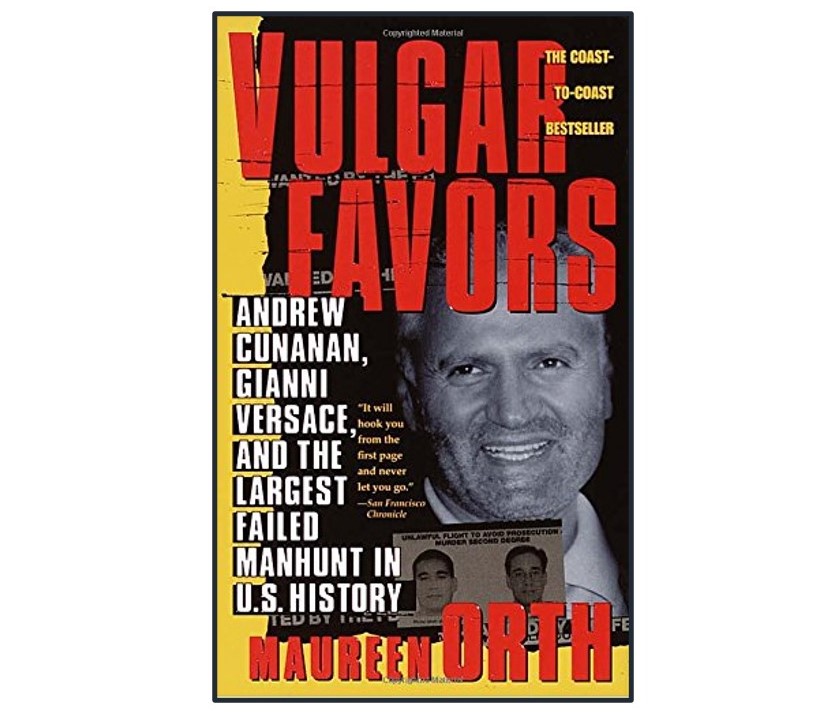

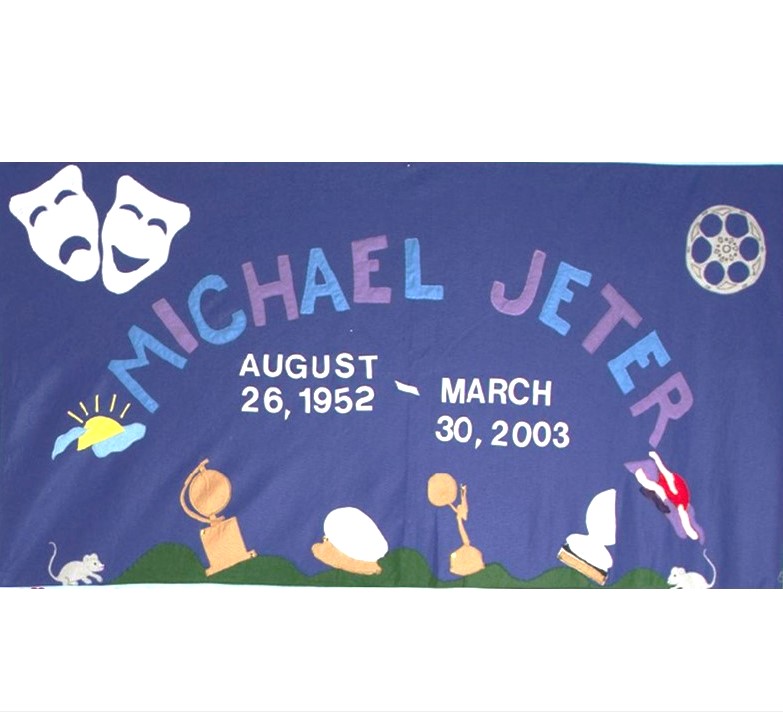

Photo of quilt panel from the AIDS Memorial Quilt

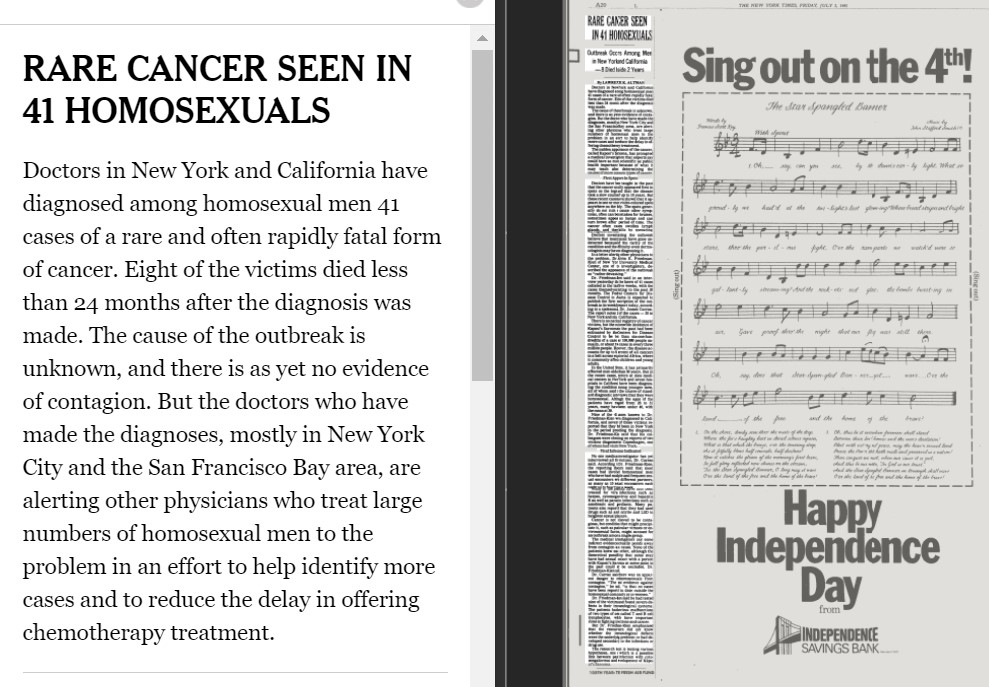

Coinciding with the CDC’s release of another MMWR detailing opportunistic infections among gay men, The New York Times publishes the article “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals.” At this point, the term “gay cancer ” enters the public lexicon.

Learn More.The CDC report, titled “Kaposi’s Sarcoma and Pneumocystis Pneumonia Among Homosexual Men — New York City and California,” described cases of KS and PCP among 26 gay men (25 white and one black, and ranging in age from 26 to 51).

In an 18-paragraph story on Page 20 of The New York Times, reporter Lawrence K. Altman cited 41 reported cases of “a rare and often rapidly fatal form of cancer.” Altman reported that eight of the 41 men diagnosed with the condition were already dead, and that the time between diagnosis and death from the disease was less than 24 months.

In the last paragraphs of the article, Altman wrote:

“The reporting doctors said that most cases had involved homosexual men who have had multiple and frequent sexual encounters with different partners, as many as 10 sexual encounters each night up to four times a week.

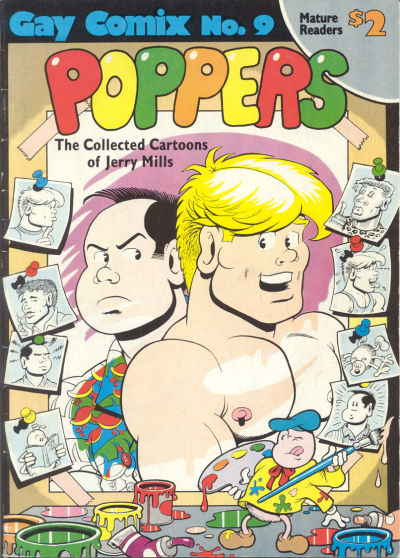

“Many of the patients have also been treated for viral infections such as herpes, cytomegalovirus and hepatitis B as well as parasitic infections such as amebiasis and giardiasis. Many patients also reported that they had used drugs such as amyl nitrite and LSD to heighten sexual pleasure.

“Cancer is not believed to be contagious, but conditions that might precipitate it, such as particular viruses or environmental factors, might account for an outbreak among a single group.”

According to Dr. Joseph Sonnabend, a New York City clinician who was among the first in the U.S. to recognize the emerging AIDS epidemic, this article was significant because of the Times‘ large, international readership. But doctors treating New Yorkers from the gay community had been noticing strange symptoms and unusual illnesses in their patients for at least two years.

“I had been observing some clinical and laboratory abnormalities among my patients as early as 1979. These included enlarged lymph glands, an enlarged spleen, low blood platelets and a low white blood cell count,” Dr. Sonnabend told POZ magazine in 2020.

“Then, in April or May of 1981, I was stunned to learn that Kaposi’s sarcoma was being diagnosed in young gay men in New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco. Joyce Wallace, a physician whose office was close to mine on West 12th Street in New York passed this information on to me,” he recalled.

When Dr. Sonnabend heard about the KS cases in young men, he reached out to a colleague, Dr. Alvin Friedman-Kien, a dermatologist at NYU medical center. Dr. Friedman-Kien was caring for several gay men with Kaposi’s sarcoma, and soon Dr. Sonnabend joined him at NYU’s virology lab.

Through their research, the doctors found high levels of interferon in their patients. Early research and discoveries like this formed the foundation of HIV/AIDS research for many years to come.

* * * * *

Sources:

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), “Kaposi’s Sarcoma and Pneumocystis Pneumonia Among Homosexual Men — New York City and California,” July 3, 1981

The New York Times, “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals” by Lawrence K. Altman, July 3, 1981

POZ magazine, “A Look Back at the Year a Rare Cancer Was First Seen in Gay Men” by Joseph Sonnabend, M.D., July 13, 2020

POZ magazine, “Interferon and AIDS: Too Much of a Good Thing” by Joseph Sonnabend, M.D., May 7, 2011

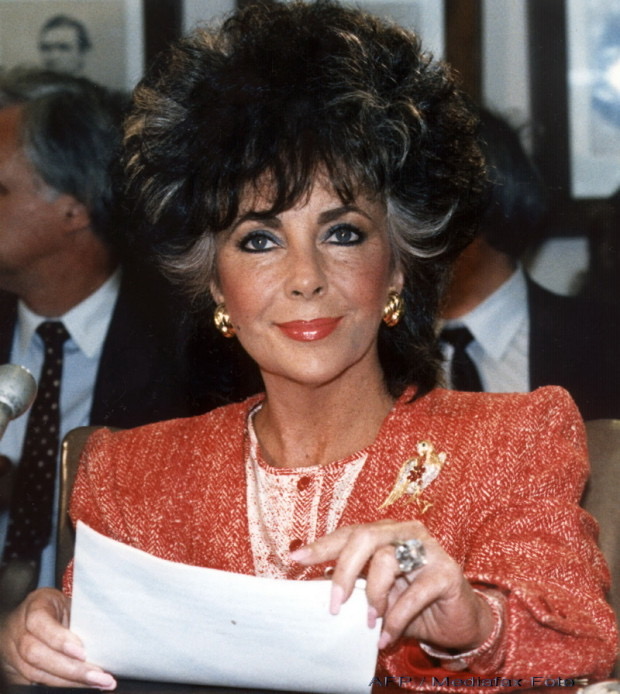

A pregnant Elizabeth Glaser, wife of television star Paul Michael Glaser, is rushed to Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles to give birth to her first child. She hemorrhages heavily during labor and requires a transfusion of seven pints of blood.

Learn More.A former teacher who worked as exhibit director of the LA Children’s Museum, Glaser asked her doctor about the mysterious disease reported recently in the press, and her doctor dismissed her concerns, assuring her, “Your nightmare is over.”

In 1985, daughter Ariel experienced persistent stomach pains and doctors were unable to determine the source. The four-year-old was tested for HIV “as just a precaution,” and the results came back positive for the virus.

Each member of the Glaser family was then tested, and would result in the additional HIV diagnosis of mother Elizabeth and 18-month-old son Jake.

Doctors determined that Elizabeth contracted HIV during her 1981 blood transfusion, and Elizabeth had unknowingly passed the virus on to Ariel through breastfeeding. Jake, who was born in October 1984, had contracted the virus in utero.

When Elizabeth sought counseling for Ariel, she discovered that no child psychiatrist would take the case. Aware of the stigma of AIDS, the Glasers pulled Ariel out of nursery school and erected a wall of secrecy to protect their children.

In August 1989 (one year after Ariel died of AIDS-related illness), the National Enquirer and other tabloids threatened the Glaser family with exposure.

Elizabeth Glaser would side-step the media ambush by sharing her harrowing story in her 1991 autobiography, In the Absence of Angels. She and two frinds then started the Pediatric AIDS Foundation, and she became one of the most aggressive and effective pediatric AIDS activists in the country.

* * * * *

Sources:

Washington Post, “AIDS: The Glaser Family’s Battle” by Janet Huck, August 28, 1989

Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation, “Elizabeth’s Story”

The New York Times, “The Youngest Victims of AIDS” by Bettyann Kevles, March 3, 1991

Forbes, “Before Charlie Sheen, They Went Public With HIV” by Barron Lerner, November 17, 2015

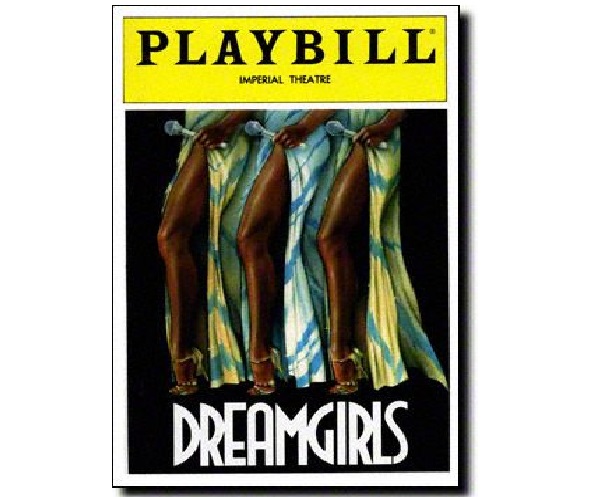

Dreamgirls makes a splashy debut on Broadway with stars Jennifer Holliday and Sheryl Lee Ralph, who both begin raising money for AIDS research and other programs after experiencing the loss of some of their cast mates to the disease.

Learn More.The successful debut of Dreamgirls marked career breakthroughs for Holliday and Ralph, but it also marked the start of a time of great loss.

In addition to cast members, Dreamgirls Director Michael Bennett would die of AIDS-related illness on July 2, 1987 at the age of 44. He would be diagnosed with AIDS in 1986 and choose to keep his illness a secret from all but a few close friends.

“Friends and cast members just got sick and died,” Ralph would later write in the Huffington Post. “They were sick today and dead tomorrow…. Then the deadly silence would set in because nobody wanted to talk about it, much less do anything about that disease, that shhhhh, gay disease. The silence was deafening.”

Ralph would go on to found the DIVA Foundation, which raises awareness about HIV/AIDS. DIVA stands for Divinely Inspired Victoriously Aware.

“It got to the point I couldn’t cross one more name out of my phone book, back when folks had such a thing called a phone book, when you would actually write a name in a book. That many people [died],” Ralph said in a 2008 Star Tribune interview.

Also, Holliday would dedicate much of her life to HIV/AIDS advocacy and activism. In 2017, Holliday would release a song to benefit Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS.

“I’ve been an advocate for AIDS assistance, because it took the lives of male chorus members and the creative team of Dreamgirls,” Holliday told the Broadway Blog.

“The gay community has really been a vital part of my whole existence. It’s been a vital program under the AIDS Healthcare Foundation and the Black Leadership AIDS Crisis Coalition. They let people know that housing is available and want to serve people who need a place to stay.”

* * * * *

Sources:

The New York Times, “Stage: ‘Dreamgirls,’ Michael Bennett’s New Musical, Opens” by Frank Rich, December 21, 1981

www.RonFassler.org, “The Death and Life of Michael Bennett” by Ron Fassler, July 2, 2018

HuffPost, “Thirty Years of ‘Dreamgirls’ and AIDS in America” by Sheryl Lee Ralph, June 14, 2011

CBS News Richmond, “Sheryl Lee Ralph Raises AIDS Awareness with DIVAs,” December 4, 2019

StarTribune, “Original ‘Dreamgirl’ Sings a Song of AIDS Awareness” by C.J., February 6, 2008

Playbill, “Jennifer Holliday Releases Single to Benefit Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS” by Andrew Gans, January 26, 2017

The Broadway Blog, “Jennifer Holliday on ‘Dreamgirls,’ Being an LGBTQ Icon, and Turning 60” by Ryan Leeds

Lenny Baker, who won the 1977 Tony Award for Best Actor in a featured role (musical), dies of AIDS-related illness in a hospital in Hallandale Beach, Florida at the age of 37.

Learn More.Born Leonard Joel Baker in 1945 in Boston, he began his acting career in regional theater and spent several summers at the O’Neill Center’s National Playwrights Conference in Waterford, Connecticut. He told an interviewer in 1977 that the center was instrumental in his career, partly because he saw performances of the National Theater for the Deaf there.

”It’s perhaps because of watching them work,” Baker said, ”that I can be so brazen with comic uses of my body.”

After moving to New York City in 1969, Baker acted in Off-Broadway stage productions until making his Broadway stage debut in 1974 in The Freedom of the City. Baker won a Tony award and the Drama Desk Award as Outstanding Actor in 1977 for his performance in the musical I Love My Wife.

Baker also acted in films and television shows, including Paul Mazursky’s Next Stop, Greenwich Village (1976), for which he was nominated for a Golden Globe award. His other film credits included The Hospital (1971) and The Paper Chase (1973).

Following Baker’s death, a memorial service was held at The Public Theater, located at 425 Lafayette Street in New York City.

* * * * * *

Sources:

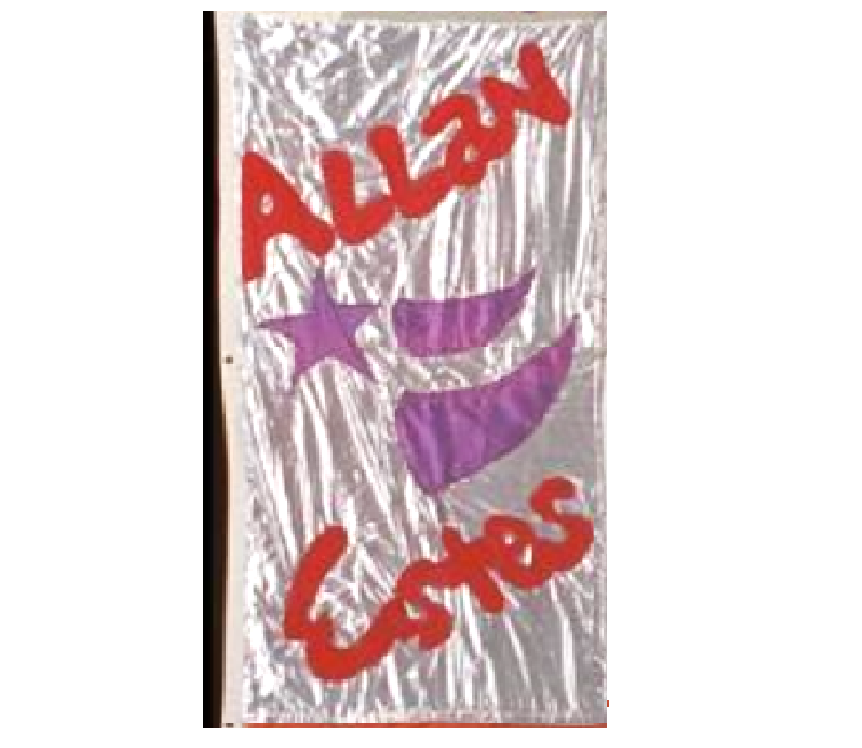

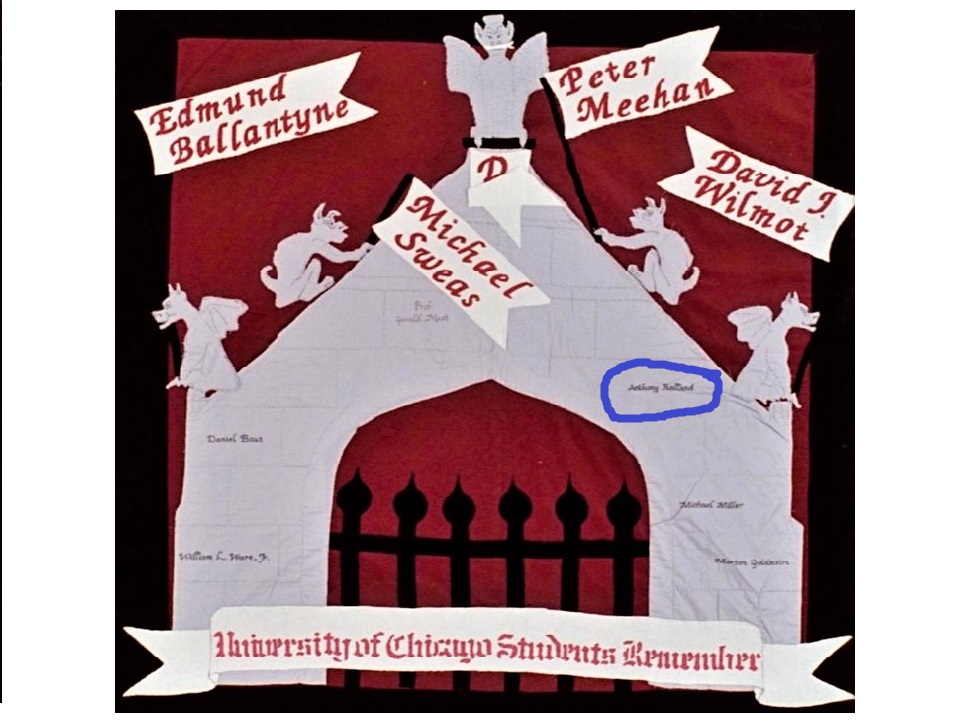

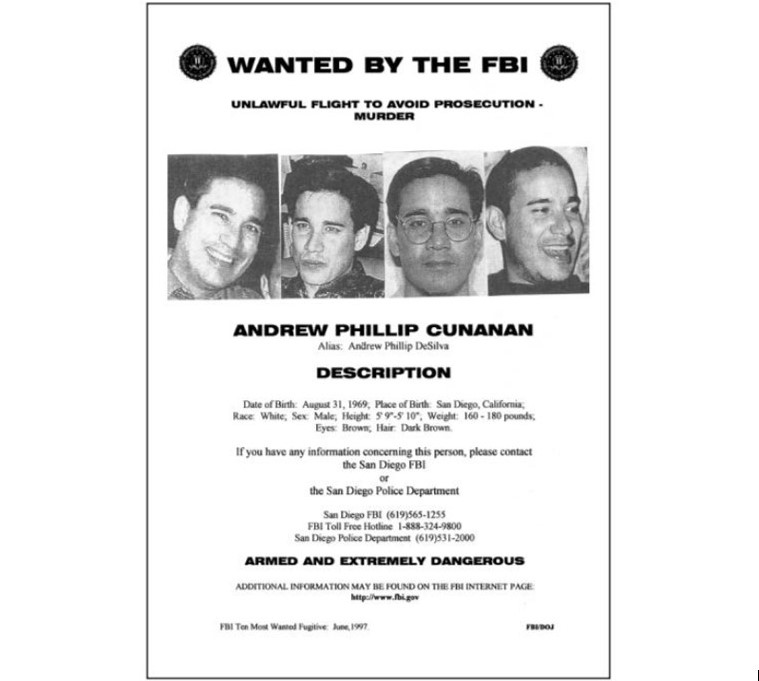

Photo of quilt panel from the AIDS Memorial Quilt

The New York Times, “Lenny Baker, 37, Stage Actor” by Eleanor Blau, April 13, 1982

IMDb, “Lenny Baker biography”

To the shock and dismay of many fans in San Francisco and New York City, The Advocate announces: “Founder of Cockettes, Hibiscus, Dead of GRID.”

Learn More.Hibiscus was famous on both coasts for founding and performing with the flamboyant theatrical groups The Cockettes and Angels of Light. He died of AIDS-related illness (then called “Gay-Related Immune Deficiency”) at St. Vincent’s Hospital in New York at the age of 32, becoming one of the earliest casualties of the epidemic.

Born George Edgerly Harris III in Bronxville, N.Y., he was the child of theater performers who relocated the family to a home on El Dorado Avenue in Clearwater Beach, Fla. Before long, George Jr. had founded his first theatrical group, the El Dorado Players, which performed in the family’s garage.

“He was fascinating even as a small child,” his mother Ann Harris told The New York Times Magazine in 2003. “All the other kids followed him and acted out his fantasies. He did Camelot one time and had the kids on bicycles with the handlebars as the horses’ heads. Another time he directed Cleopatra, and used the garden hose as the serpent and our cats as Cleopatra’s gifts to Caesar. He was very much the little producer.”

When his family returned to New York in 1964, George Jr. reprised the El Dorado Players, augmenting the troupe with children he met in Greenwich Village. He took acting and singing classes at Quintano’s School for Young Professionals, and soon he was cast as an extra in a milk commercial, a deaf-mute in a television series and an antiwar protester in an Off Broadway play called Peace Creeps, co-starring Al Pacino and James Earl Jones.

The latter role would be strangely prescient. On October 21, 1967, an 18-year-old George Jr. would be photographed placing a flower in a gun barrel pointed at him while taking part in an anti-war demonstration at the Pentagon. The photo, widely circulated in the media, became iconic of the anti-war movement and generational divide in the country.

Washington, D.C. was just a stop-over, through, of a trip he was taking to San Francisco with friend Irving Rosenthal, the author of the homoerotic novel Sheeper and the onetime lover of William Burroughs. Inspired by an image in a Cocteau novel, he changed his name to Hibiscus, and started wearing the glittery makeup, diaphanous robes and floral headpieces that would become his signature.

He joined Rosenthal’s commune, KaliFlower, which was dedicated to distributing free food and creating free art and theater. This was the fertile environment in which Hibiscus founded The Cockettes.

Hibiscus and other KaliFlower members first performed at the 1970 New Year’s Eve Show at the Palace Theater, an old Chinese movie house in North Beach. They called themselves The Cockettes, a bawdy allusion to the Rockettes, and danced a cancan to the Rolling Stones’ song Honky Tonk Women.

Under the leadership of Hibiscus, the group’s act quickly evolved into bigger, wilder, and more lavish productions, and The Cockettes’ shows fast became not-to-be-missed events. New shows were created every few weeks, with Paste on Paste, Gone with the Showboat to Oklahoma, and Tropical Heatwave/Hot Voodoo being some of the early productions.

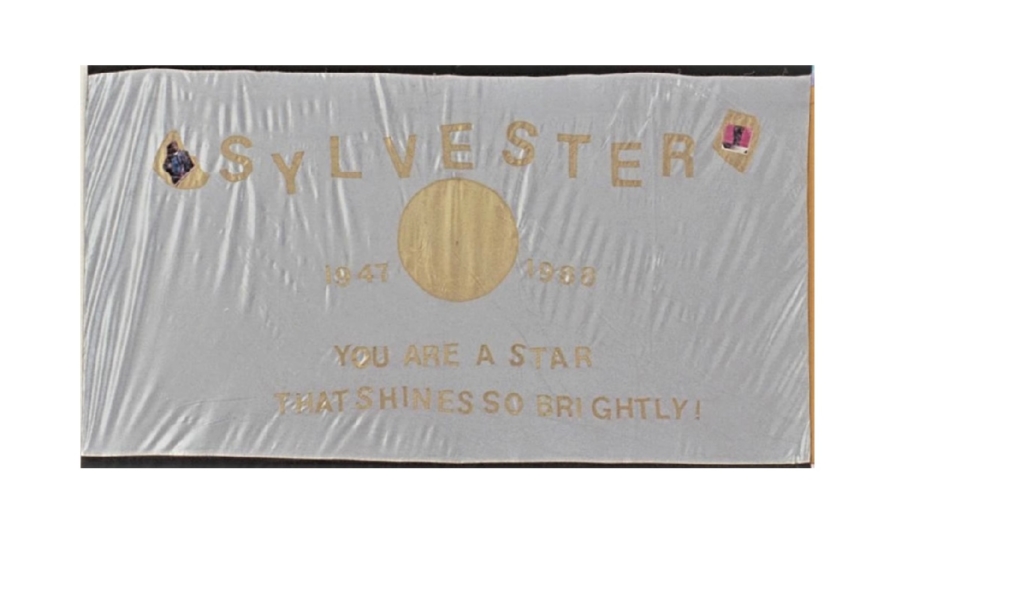

Pearls Over Shanghai became the Cockettes first show featuring an original script, music and lyrics, and was an instant hit with fans. Some members of the Cockettes, like Sylvester and Devine, began to garner their own fan followings. During this time, Hibiscus found he could express his sexual identity with fearless abandon.

”He came out of the closet wearing the entire closet,” says Nicky Nichols, a fellow Cockette.

When some members of The Cockettes began insisting that they begin charging for their shows, Hibiscus refused and found himself expelled from the group he founded. Unperturbed, Hibiscus formed a new theatrical group called the Angels of Light Free Theater. Their shows included Flamingo Stampede and The Moroccan Operette, which Hibiscus described as being ”like Kabuki in Balinese drag.”

Among the people he convinced to perform with the Angels of Light was poet Allen Ginsberg, who appeared in drag for the first time. Hibiscus found another collaborator in his new boyfriend, Jack Coe, also known as Angel Jack, who eventually moved to New York with Hibiscus in 1972, around the same time that the Cockettes disbanded.

Upon his return to NYC, he recruitd his mother and three sisters (Jayne Anne, Eloise and Mary Lou) into an east coast version of the Angels of Light.

“I wrote almost all the music for the Angels of Light,” said his mother, Ann. “George would say, ‘Oh, I need a sheik scene, with a sheik in it,’ and then I would come up with a song.”

The group performed at the Theatre for the New City, where John Lennon was known to jump on the stage and sprinkle glitter on Hibiscus.

In the early 1980s, he and his sisters and brother formed the glitter rock group “Hibiscus and the Screaming Violets,” supported by musicians Ray Ploutz on bass, Bill Davis on guitar and Michael Pedulla on drums. But he had to stop performing in 1981 due to his escalating illness.

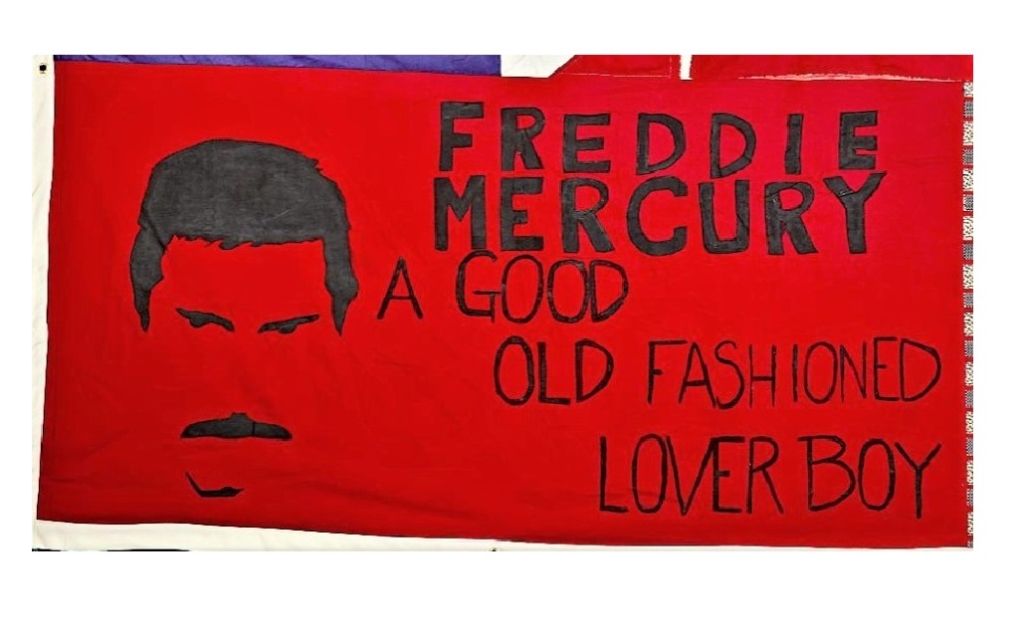

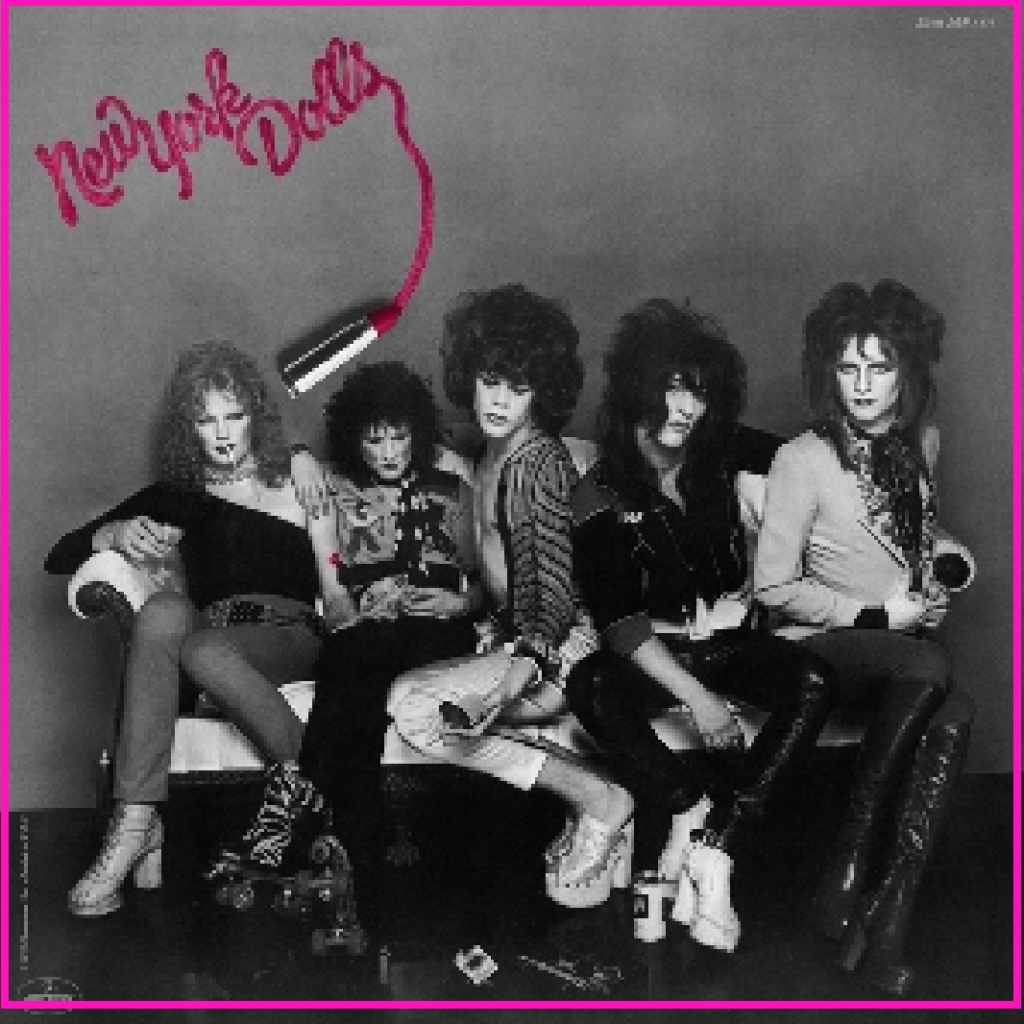

It’s testament to the power of his personality and creativity that the spirit of Hibiscus dominates the 2002 Cockettes documentary, even though the film’s focus is on the group. Decked out in gender-bending drag and tons of glitter, the flamboyant ensembles of both The Cockettes and Angels of Light are considered to be the inspiration for later theater productions like The Rocky Horror Picture Show and acts like The New York Dolls.

* * * * * *

Sources:

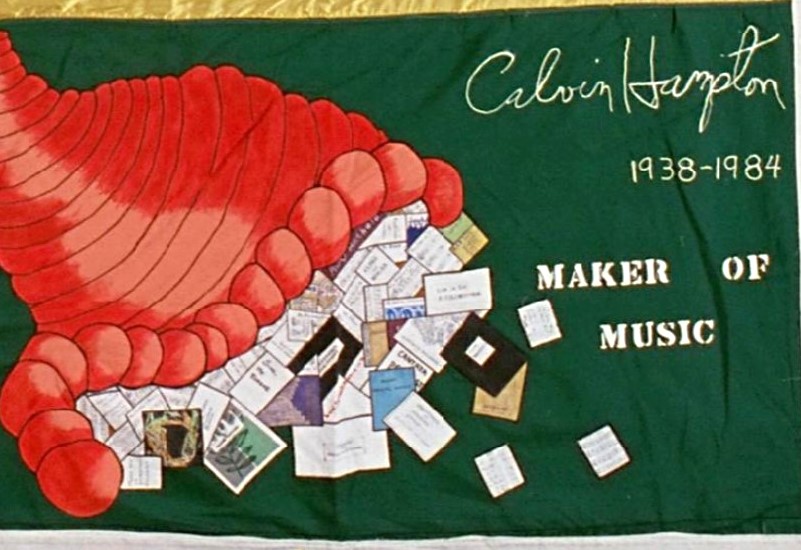

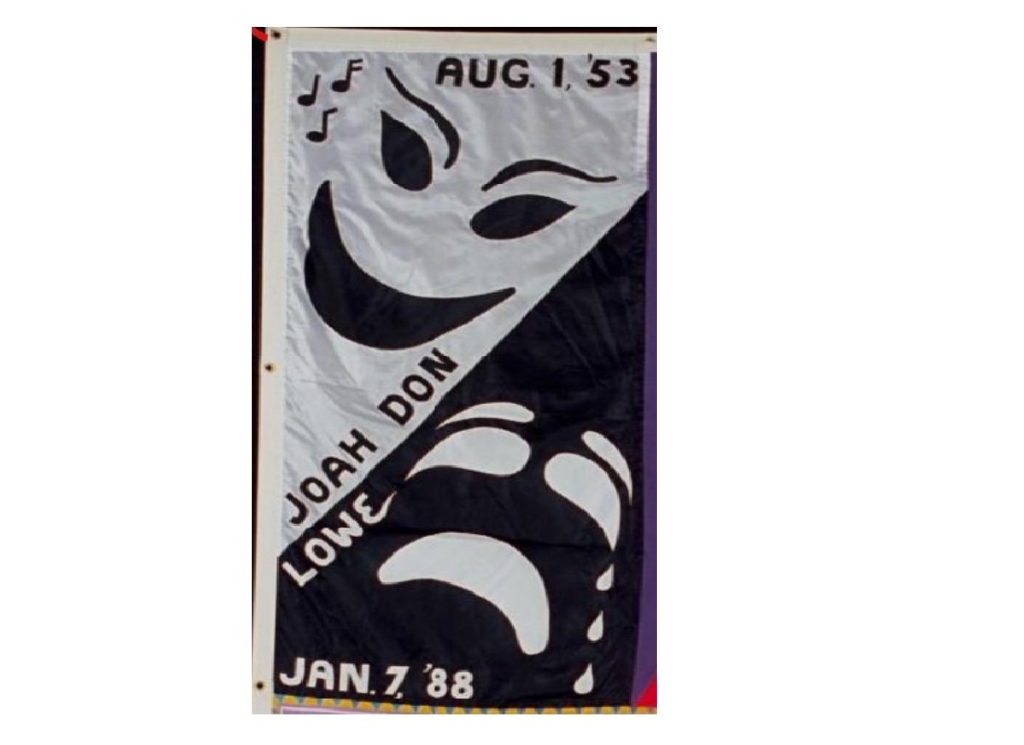

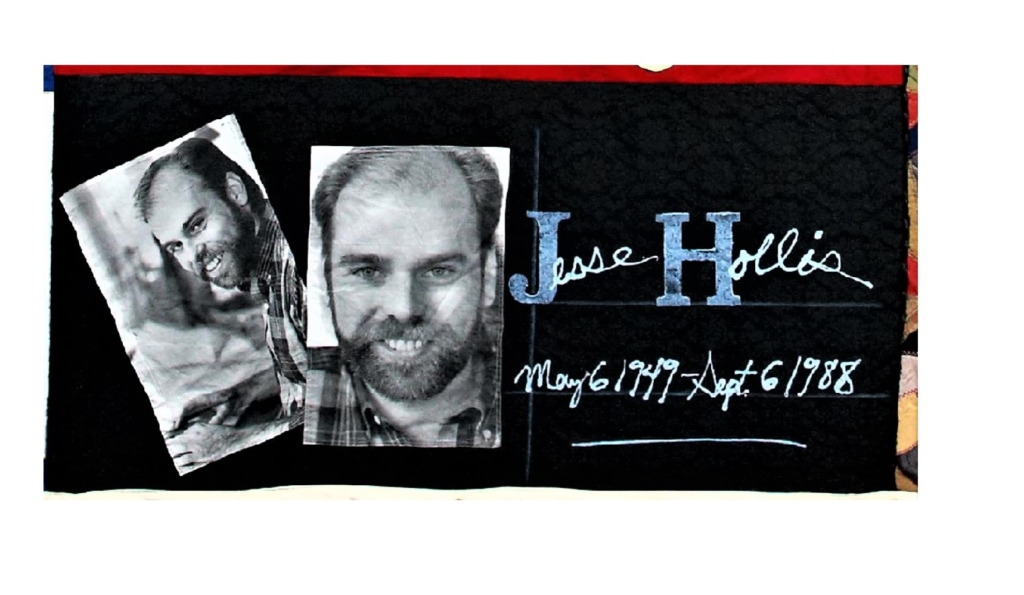

Photo of quilt panel from the AIDS Memorial Quilt

The New York Times Magazine, “Karma Chameleon” by Horacio Silva, August 17, 2003

The Washington Post, “Flowers, Guns and an Iconic Shapshot” by David Montgomery, March 18, 2007

The Cockettes, A Film by David Weissman and Bill Weber, 2002 (trailer)

Hibiscus and the Angels of Light, video (YouTube)

The New York Times publishes the first media mention of the term “GRID” (Gay-Related Immune Deficiency), deepening public perceptions that HIV/AIDS is solely related to homosexuality.

Learn More.Under the headline “New Homosexual Disorder Worries Health Officials,” the Times introduced its readers to “a serious disorder of the immune system” that had proved fatal in 136 people to date.

“It was colloquially referred to as GRID – ‘Gay Related Immune Deficiency’ or ‘Gay Related Immune Disease,’ as if there was something intrinsic about being gay that made people susceptible to it,” wrote Carla Tsampiras in The Conversation.

While the Times article identified 13 cases of the disease in heterosexual women, it went on to state, “Most cases have occurred among homosexual men, in particular those who have had numerous sexual partners, often anonymous partners whose identity remains unknown.”

Even once the disease was renamed HIV/AIDS, the stigmatization continued. Early research elicited categories of people, referred to as “high-risk groups,” who were apparently at increased risk of having AIDS. They were informally known as “the Four-H Club” — homosexuals, Haitians, hemophiliacs and heroin users. Later, “hookers” were added to the list.

“As a result, AIDS avatars — such as The Homosexual, The Prostitute, and The Drug Abuser — were created, drawing on long histories of social and medical prejudice and othering of certain groups of people,” said Carla Tsampiras, Senior Lecturer in Medical Humanities at the University of Cape Town. “The avatars drew on existing stereotypes and reinforced them, reflecting existing prejudices or social attitudes relating to sexuality, sexual orientation, race, class and gender.”

* * * * * *

Sources:

The New York Times, “New Homosexual Disorder Worries Health Officials” by Lawrence K. Altman, May 11, 1982

The Conversation, “AIDS: What Drove Three Decades of Acronyms and Avatars?” by Carla Tsampiras, June 4, 2015

The Los Angeles Times publishes the story “Mysterious Fever Now an Epidemic” on its front page, marking the first time the disease receives top coverage in the mainstream media.

Learn More.* * * * * *

Source:

Los Angeles Times, “Anti-Gay Bias? : Coverage of AIDS Story: A Slow Start” by David Shaw, December 20, 1987

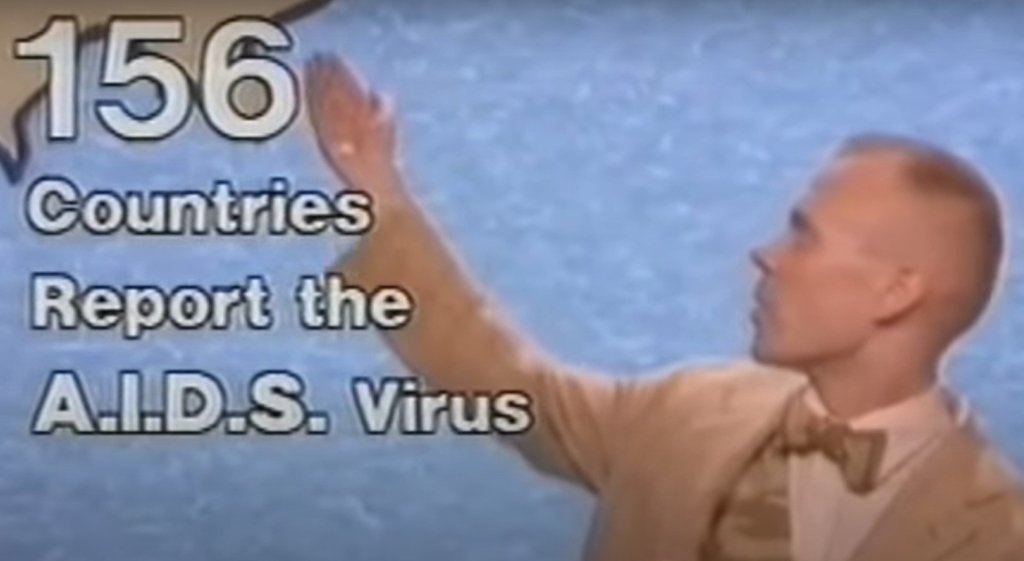

In one of the earliest broadcast news stories about AIDS, reporter Barry Peterson interviews gay men diagnosed with Kaposi’s Sarcoma.

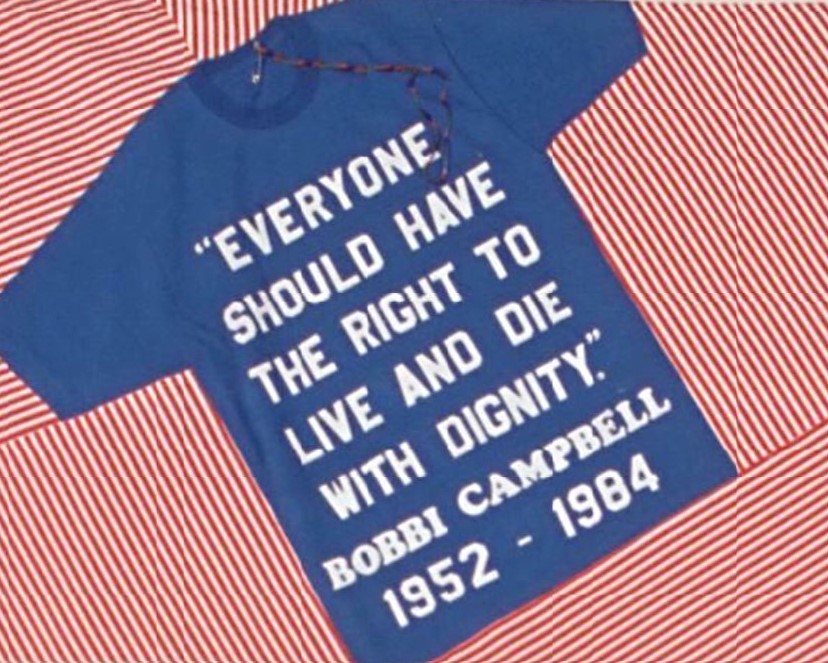

Learn More.The news segment opens with AIDS activist Bobbi Campbell talking about his shock at the age of 29, when he was told he had a deadly form of cancer. Then, the segment shows Campbell being examined by his doctor, Marcus Conant, M.D.

Next, New York-based AIDS activist Larry Kramer talks about how the disease is killing more people than toxic shock syndrome and Legionnaire’s disease — two bacterial infections receiving a lot of media attention at the time. When the reporter asks Campbell why no one is addressing the AIDS epidemic, Kramer replies, “Well, I think it’s because it’s a gay cancer.”

James Curran, M.D., speaks on behalf of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, telling CBS News that now is the time to conduct AIDS research to determine how the disease was being transmitted. The reporter notes that “there is almost no money being spent so far” for AIDS research.

The reporter closes the segment with this statement: “For Bobbi Campbell, it is a race against time. How long before he and others who have this disease finally have answers, finally have the hope of a cure?”

Campbell would die of AIDS-related illness on August 15, 1984, about 26 months after the report aired on CBS News.

It would be almost 12 years later (1996) before highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) would become widely available to people living with HIV/AIDS, finally offering the hope of survival. Deaths from AIDS-related illness fell almost immediately in the industrialized world, and the way we think about HIV and AIDS changed forever.

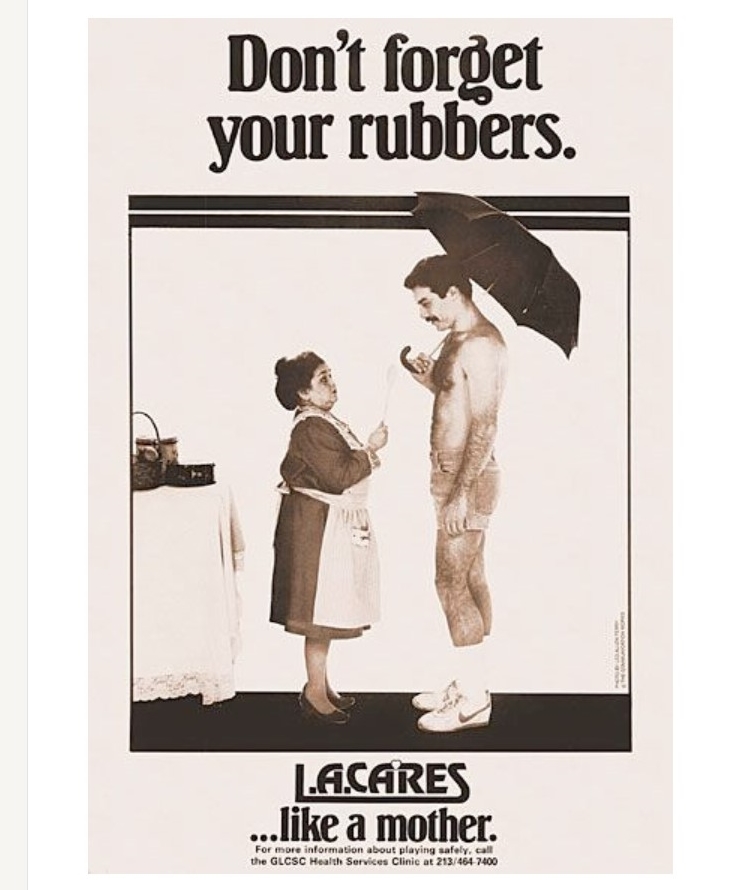

The Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence creates Play Fair! — the first “safer sex” pamphlet to address the growing AIDS epidemic.

Learn More.The Sisters distributed 16,000 copies of Play Fair! during the San Francisco Gay & Lesbian parade in June 1982.

Written by Sister Florence Nightmare and Sister Roz Erection, who outside the Order were known as registered nurses Bobbi Campbell and Baruch Golden, Play Fair! was among the first guides promoting safe sex and raising awareness around sexually transmitted diseases.

The Sisters originated in 1979 with three gay men who wanted to combine radical politics, street theater, and high camp, according to Will Kohler. Having obtained nuns’ habits from a community theater production of The Sound of Music, these men (a.k.a., Sister Vicious Power Hungry Bitch, Sister Missionary Position, and Sister Roz Erection ) turned heads as they strolled Castro Street on Easter Sunday.

By 1982, the Sisterhood had many members and promoted a lively campaign around sex-positivity through a combination of fundraising, community outreach and events. With growing anxiety and concern around the spread of Kaposi’s sarcoma and other immune disorders among gay men, it was inevitable that the Sisters would incorporate AIDS awareness into its mission.

For over 40 years, the order of queer and trans nuns has been spreading its ministry across San Francisco, the U.S., and the world. Each professed nun takes a religious name (usually irreverent and hilarious). For example, cities, events and venues have been ministered to by Sisters Psychedelia, Hellen Wheels, Innocenta, Rhoda Kill, Lotti Da, and Hysterectoria.

Although originally founded as an “Order of Gay Male Nuns,” the group now includes gay, lesbian, bisexual, heterosexual, and transgendered men and women. Many of their rituals are influenced by Eastern religious practices and beliefs, as well as by Roman Catholicism. Their doctrine stresses universal joy and the expiation of guilt.

Members of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence who have died are referred by the Sisters as “Nuns of the Above.”

* * * * * *

Sources:

The Sisters Of Perpetual Indulgence, “Sistory”

The Abbey of St Joan, “Play Fair”

Back2Stonewall, “Gay History – April 15, 1979: San Francisco’s Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence Founded,” April 16, 2022

The Culture Trip, “Meet the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, San Francisco’s Order of Queer Nuns” by Deanna Morgado, July 3, 2019

GLBTQ Archive, “Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence” by Robert Kellerman, 2002

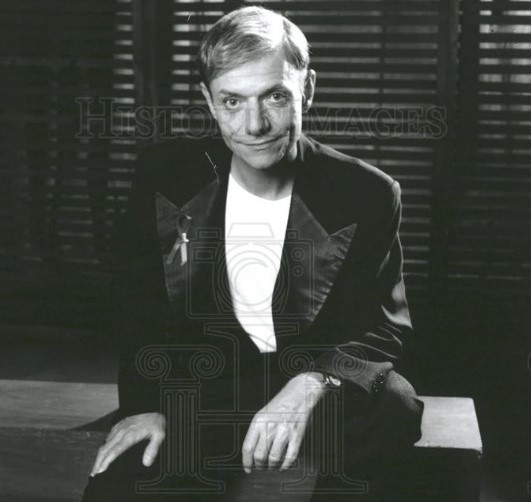

Louis “Lou” Maletta launches the Gay Cable Network on Manhattan cable channel 35, starting with the program Men in Films and then expanding its programming to include news about the AIDS crisis.

Learn More.The Gay Cable Network broke new ground by providing television programming from a gay perspective, and often featured news about AIDS that was broadcast nowhere else in the country. While the network existed on Manhattan cable in New York City, Maletta also made his programs available to other cities like San Francisco, Cincinnati and Atlanta, which broadcast his taped programs.

Maletta’s first program, Men & Film, featured strategically edited gay pornographic material that “just barely passed even early cable access censorship standards,” according to Back2Stonewall, Maletta would announce at the start of each show that his goal with the program was to “put the male body back on the map.”

Within months, Maletta expanded his programming to include news, sports and entertainment, and the network became a forum for a range of issues facing the gay community.

In a 2009 interview with Gay City News, Maletta said he realized he needed to provide gay-centric programming about the AIDS crisis after he witnessed a 30-year-old friend become “someone who looked 90 six months after being diagnosed.”

Maletta arranged for officials from New York City’s health department and Gay Men’s Health Crisis to provide updates on HIV/AIDS healthcare and research developments.

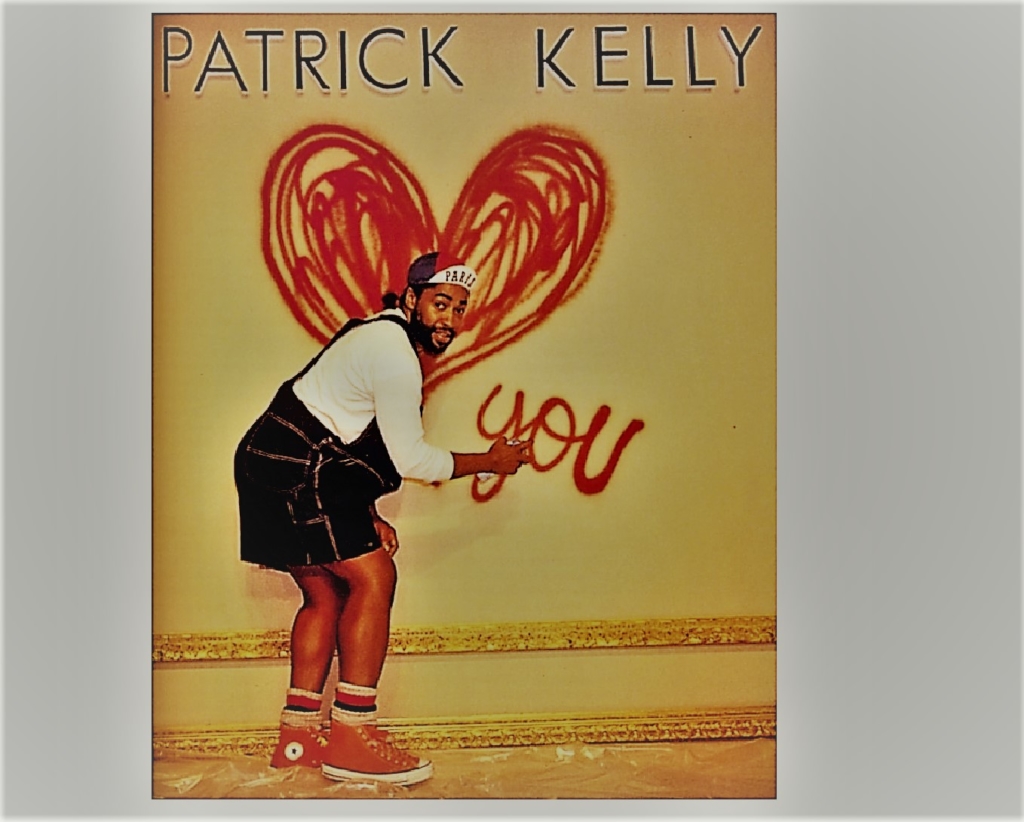

Maletta’s Gay Week in Review was sponsored by the Human Rights Campaign, and Naming Names was produced weekly by the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation, according to Gay City News. Maletta himself covered arts and entertainment in a show called Be My Guest, which featured celebrities including Harvey Fierstein, Derek Jarman, Vito Russo, Patrick Stewart, Tony Kushner, Quentin Crisp, and Divine.

The network’s news program, Pride and Progress, eventually became Gay USA, a show co-hosted by Ann Northrop and Andy Humm that outlived the network and today is distributed nationally by Free Speech TV.

Gay USA covered the Democratic and Republican national conventions from 1984 to 2000 with reporters interviewing political leaders from Dick Cheney and George W. Bush to Jesse Jackson and Ann Richards. The news program also covered AIDS demonstrations outside the conventions, as well as numerous rallies in Washington and New York City.

“It was critical to the LGBT rights movement,” Kenneth Sherrill, a political science professor at Hunter College, told The New York Times. “Mainstream television wasn’t rushing to cover the movement, and public access cable provided entrée for social and political groups that were traditionally excluded. Lou Maletta’s programming allowed voices of the gay community to speak for themselves.”

Maletta videotaped his programs at first out of his apartment on West 15th Street, which he shared with Luke Valenti, his domestic partner of 37 years, according to Gay City News. Later, Maletta operated out of Manhattan buildings that doubled as sex clubs late at night.

“There was nothing quite like bringing a candidate for public office in for an interview with an erotic mural looking down at them from off-stage and lubricant residue still on the chairs,” Humm of Gay USA wrote. “But no one walked out and many sought the chance to be on the shows, including Ed Koch and David Dinkins when they ran against each other for mayor in 1989.”

In 2001, Maletta would shut down the network. He died in upstate New York about 10 years later of liver cancer at the age 74.

“He had a tremendous vision and unlike most people, he acted on it and made it happen. Because he was such a rebel and way before his time, he didn’t reap the benefits, which could make him cranky and difficult. But he is a really important figure in our community,” said Northrup of Gay USA.

“Lou had this grand vision of a 24-hour gay cable network,” Humm of Gay USA told The New York Times. “That didn’t happen for him.”

Still, Maletta’s legacy continues with the endurance of Gay USA and the introduction in 2005 of Logo, a gay-oriented 24-hour cable channel, wrote NYT reporter Dennis Hevesi.

In 2009, the entire archives of the Gay Cable Network were acquired by New York University’s Fales Library for restoration, and preservation.

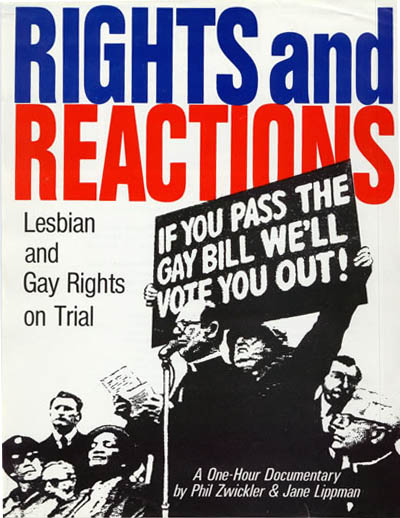

“It’s more than 6,000 hours of film about civil rights and human rights,” said Allen Zwickler, who brokered the deal with NYU. Zwickler’s brother Phil was a documentarian and GCN correspondent before he died of AIDS-related illness in 1991 at the age of 36. “It is so incredible that it had to be preserved.”

Larry Hinneman, a dancer with the Margaret Jenkins Dance Company in San Francisco, dies of AIDS-related illness.

Learn More.The exact date of Hinneman’s death is not known, nor is his age at the time of his death.

* * * * * *

Source:

San Francisco Chronicle, “AIDS at 25” by Steven Winn, June 8, 2006

In their New York Native article “We Know Who We Are,” Michael Callen and Richard Berkowitz suggests “excessive promiscuity” as a risk factor for contracting AIDS.

Learn More.Callen and Berkowitz, who wrote the article with the assistance of Callen’s partner Richard Dworkin, were New Yorkers living with AIDS.

After seeing the disease quickly progress and kill people they knew, they wanted to do something that could save lives. In their article, they warned readers against “the cumulative effects of re-exposure to CMV [cytomegalovirus] and other infections.”

“Deep down, we know who we are and why we are sick,” they wrote for the November 8, 1982 edition of the gay weekly.

The reason why men were sick, they theorized, was because they lived a life of “excessive promiscuity on the urban gay circuit of bathhouses, backrooms, balconies, sex clubs, meat racks and tearooms.”

Callen and Berkowitz argued that AIDS was caused by a combination of factors associated with a “promiscuous lifestyle” – drug use, multiple sexual partners and repeated exposure to other sexually-transmissible infections.

After publication, the article drew a torrent of angry criticism from readers of the Native, as well as from gay periodicals across North America, including the Toronto newspaper Body Politic, which accused Callen and Berkowitz of creating unnecessary panic in the community and working against the tide of gay liberation.

“It was widely criticized – not least because it had no scientific basis, and also because it assumed that all gay men with AIDS had lived so-called ‘promiscuous’ lifestyles,” said Colin Clews, author of Gay in the ’80s.

Even so, the article served as a clarion call for many and offered a considerable amount of information that could be useful to its readers:

The article also included these remarkably prescient suggestions:

Still, the criticism from the community stung. In the months that followed, Callen turned his attention to his personal life, tending to his own health and that of friends. But Berkowitz was not deterred; he began a new project which would eventually become the 46-page groundbreaking pamphlet How to Have Sex in an Epidemic.

Callen would eventually work with Berkowitz on the new project, and they would both take what they learned from the reponse to their Native article to develop an entirely new approach to fostering AIDS awareness. Published in the summer of 1983, How to Have Sex in an Epidemic would be embraced by the community and eventually have a widespread impact on the sexual practices of gay men.

* * * * *

Sources:

Richard Berkowitz Files, “We Know Who We Are: Two Gay Men Declare War on Promiscuity” by Michael Callen and Richard Berkowitz with Richard Dworkin

Gay in the ’80s by Colin Clews (self-published)

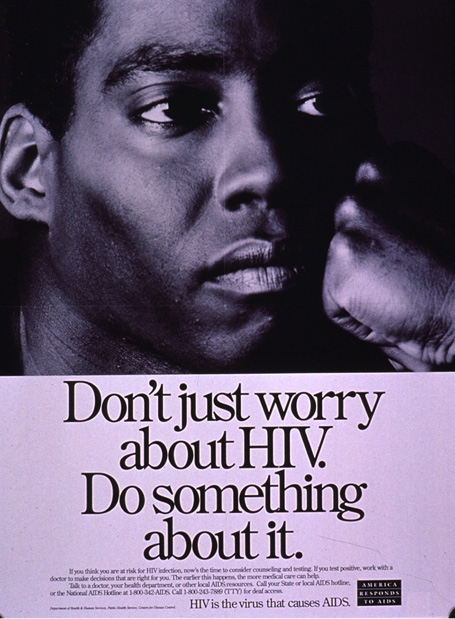

The U.S. Health & Human Services Department launched the National AIDS Hotline (NAH). and by the end of the first month, it’s receiving 8,000-10,000 calls a day.

Learn More.Operated by the U.S. Public Health Service, the AIDS Hotline responds to public inquiries about the disease, and by July 28, the hotline has to be expanded from three phonelines to eight to accommodate the high volume of calls.

In 1985, HHS transferred the hotline to the Center for Disease Control and eventually services were expanded in October 1987 to become the National AIDS Clearinghouse, with electronic linkage to computerized referral databases.

Spanish-languages services on the hotline were not included until August 1988. A month later, the hotline adopted TTY services for the hearing-impaired.

By February 1991, the total of calls to the hotline in eight years of service was 5 million.

* * * * * *

Source:

National AIDS Hotline: HIV and AIDS Information Service through a Toll-Free Telephone System by Robert R. Waller and Lynn W. Lisella (CDC’s HIV Public Information and Education Programs, November-December 1991)

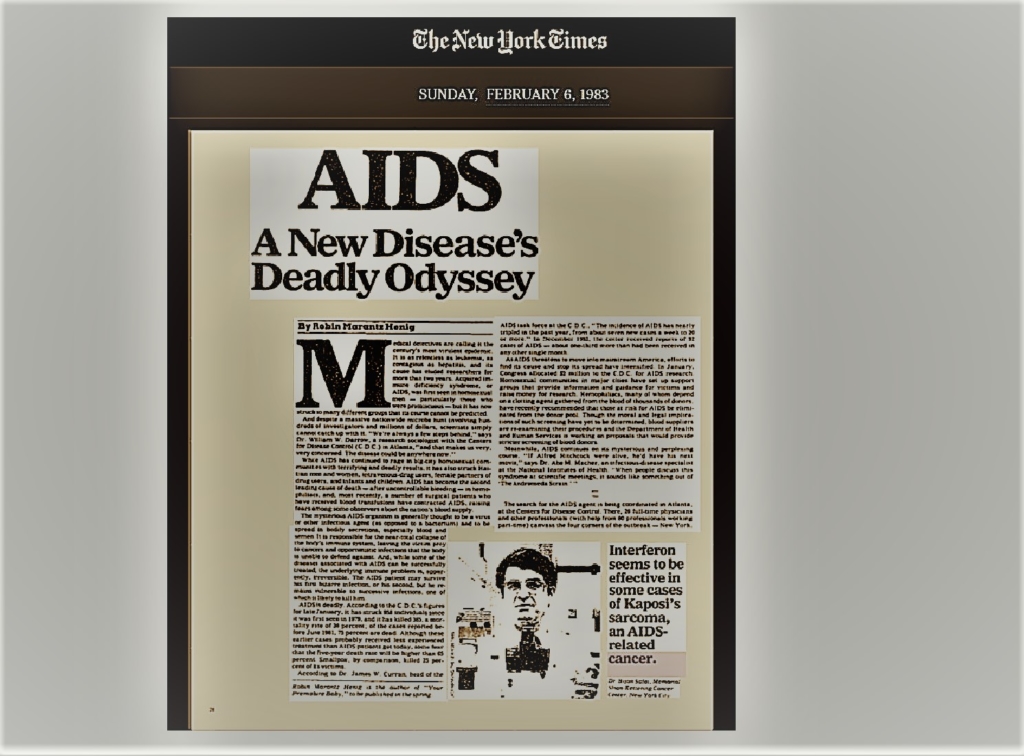

The New York Times Magazine releases “AIDS: A New Disease’s Deadly Odyssey,” the first indepth article on AIDS in the mainstream press.

Learn More.The article describes how the virus — “the century’s most virulent epidemic” — is spreading in “big-city homosexual communities” and has become the second-leading cause of death in hemophiliacs.

Dr. James W. Curran, head of the AIDS task force at the Centers for Disease Control, told the NYT Magazine reporter that AIDS was moving into mainstream America, and scientists still have not identified the disease’s cause or a way to stop its spread.

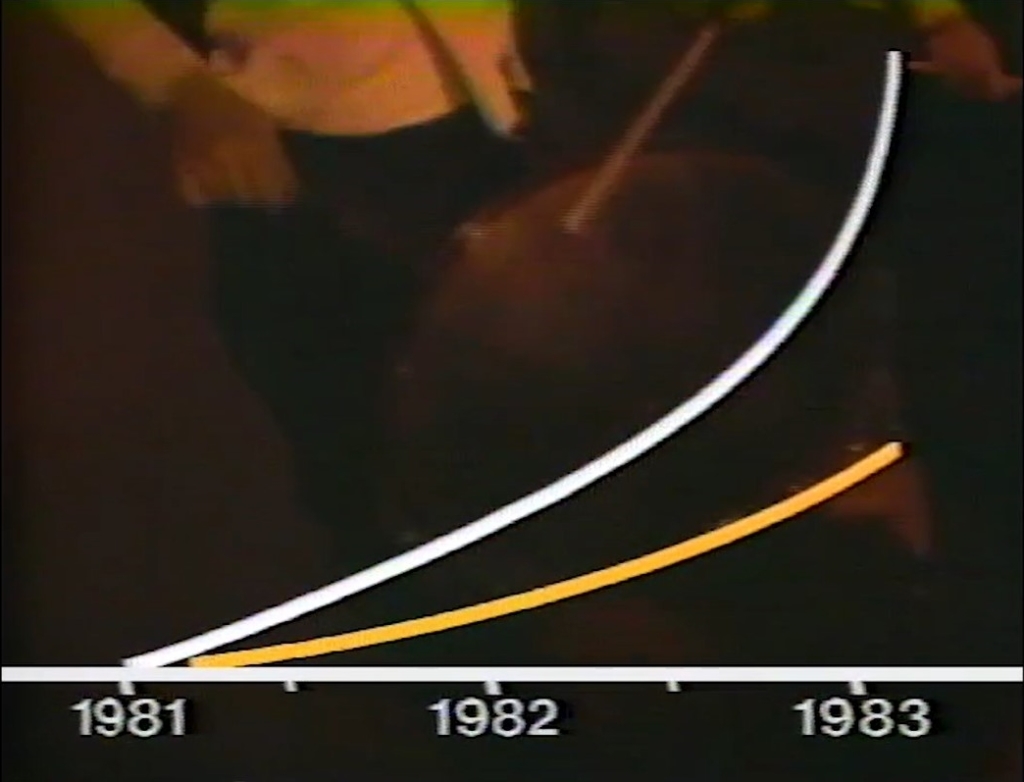

“The incidence of AIDS has nearly tripled in the past year, from about seven new cases a week to 20 or more,” Dr. Curran says, citing recently released data that shows that the CDC received reports of 92 cases of AIDS in December 1982, about one-third more than had been received in any other previous month.

The article describes how the CDC is struggling to identify the cause of AIDS. The work is being done by 20 full-time physicians and other professionals, with help from 80 professionals working part-time, focusing on four locations of the outbreak – New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles and Miami.

The medical investigators have bee able to broadly trace the spread of the disease, the article states.

Beginning in spring 1981, clinicians in New York City began to see a surprising number of young male patients with Kaposi’s sarcoma, an extremely rare cancer usually seen in elderly Mediterranean men

At about the same time, infectious-disease specialists throughout the city noted a surge in another rare disease, Pneumocystis pneumonia. At the weekly citywide infectious-disease meetings sponsored by the city’s Department of Health, where physicians present their most perplexing cases, medical professionals started sharing information about these cases.

In mid-1981, the CDC formed a special task force to investigate these unusual cases, and then published its first findings in June and July in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Of the 116 patients identified at the time, about 30% had Kaposi’s sarcoma, about 50% had Pneumocystis pneumonia, and about 10% had both. The remaining 10% had unusual infections that also usually occur in immunosuppressed patients.

Half of the case subjects lived in New York City, and the next-largest group lived in California. An indepth study of 13 patients in Los Angeles conducted by Dr. William W. Darrow and Dr. David Auerbach, both CDC researchers, was able to compare a list of all the sex partners that the patients (or their survivors) could name for the previous five years with a roster of all the AIDS cases in the country.

The result of the comparison revealed that nine of the 13 case subjects had common sexual contacts. This was the so-called “LA cluster” of AIDS patients. Later, a missing link was found between LA and NYC: a patient from New York was identified as having been a sexual partner of four men in the LA cluster, as well as of four NYC men who also developed AIDS.

The widely-read article also quoted activist Larry Kramer: “You don’t know what it’s like to be gay and living in New York. It’s like being in wartime. We don’t know when the bomb is going to fall.”

Kramer described losing 18 friends in the previous 18 months to AIDS, and said another 12 are seriously ill.

“Doctors and psychiatrists are pleading with the community to learn a new way of socializing. They’re begging us, in the name of all who died, to learn how to date,” said Kramer.

The article also addresses the issue of whether the nation’s blood supply is safe. At the time, the CDC had received a total of eight confirmed reports of hemophiliacs with AIDS, six of whom have died.

”I’m concerned and worried,” says Dr. Joseph Bove, chairman of the American Association of Blood Banks committee on transfusion-transmitted diseases and a professor of laboratory medicine at the Yale University School of Medicine. ”But as a scientist, I have to look at the evidence. And the evidence is that ordinary blood transfusions are not transmitting AIDS.”

Dr. Bove cited the number of people who had received transfusions in the two years since AIDS was first identified — 20 million — and claimed that there was no “epidemic of AIDS spread by blood.”

Dr. Bruce L. Evatt, director of the CDC’s Division of AIDS,” said Dr. Evatt, adding that while the risk appears to be low, it may increase significantly.

At the time the article was published, the CDC had received reports of 958 individuals with the AIDS virus, and 365 were already being treated for the deadly symptoms of AIDS.

* * * * * *

Source:

New York Times Magazine, “AIDS: A New Disease’s Deadly Odyssey” by Robin Marantz Henig,

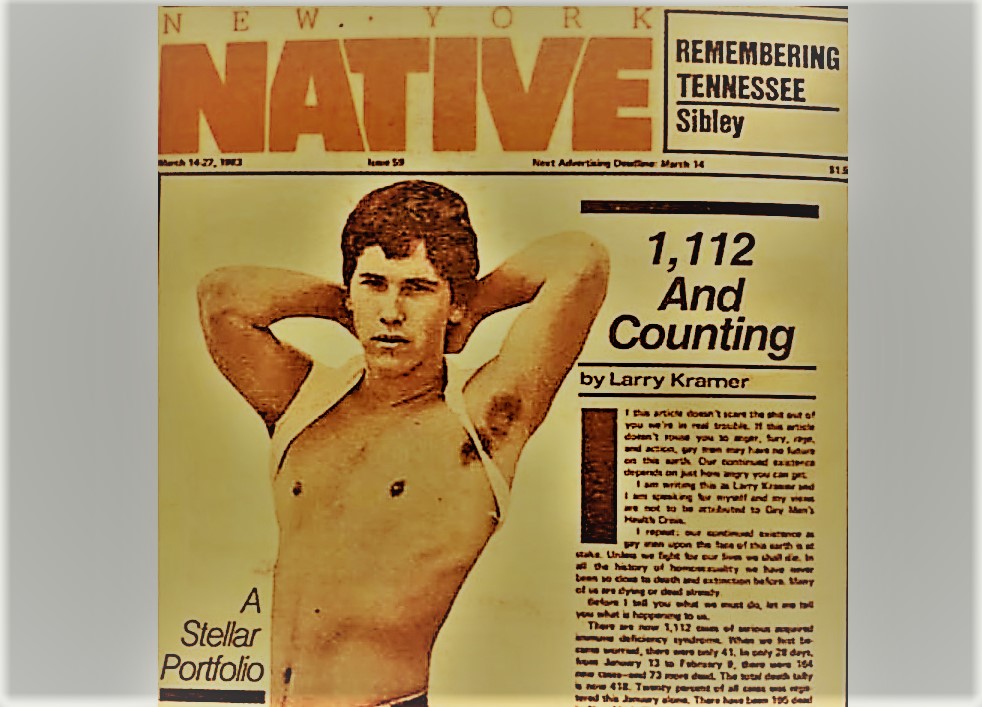

Readers of the New York Native take notice of “1,112 and Counting,” AIDS activist Larry Kramer’s urgent plea for the NY Gay Community to get angry at the lack of government support and scientific advances in the fight against AIDS.

Learn More.Published in the New York Native, Kramer provides a blistering assessment of the impact of AIDS on the gay community, the quickly rising numbers of sick and dying gay men and the slow pace of scientific progress in finding a cause for AIDS.

Kramer’s historic essay opens with:

“If this article doesn’t scare the shit out of you, we’re in real trouble. If this article doesn’t rouse you to anger, fury, rage, and action, gay men may have no future on this earth. Our continued existence depends on just how angry you can get.”

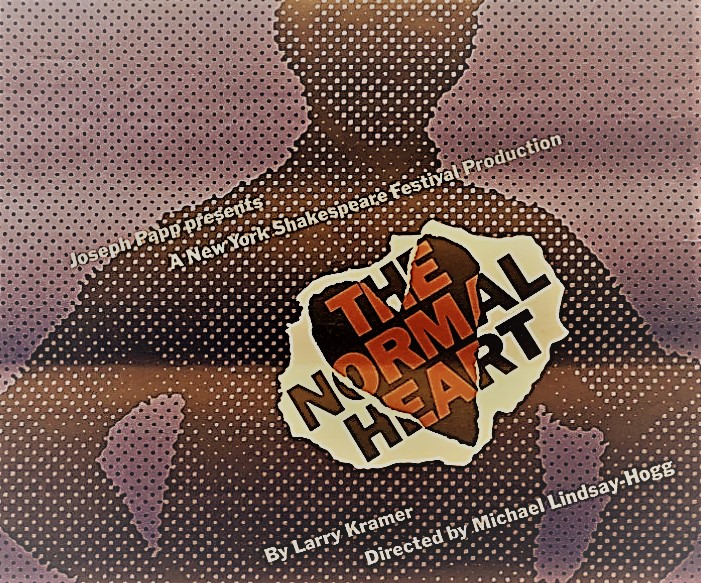

This essay was just the beginning for Kramer, in what would become a lifetime of activism and advocacy. He would go on to write The Normal Heart, the first serious artistic examination of the AIDS crisis, and he would found ACT UP, a protest organization widely credited with having changed public health policy and the public’s awareness of HIV and AIDS.

“There is no question in my mind that Larry helped change medicine in this country. And he helped change it for the better. In American medicine there are two eras. Before Larry and after Larry,” said Dr. Anthony Fauci.

* * * * * *

Sources:

New Yorker Magazine, “Larry Kramer, Public Nuisance,” by Michael Specter, May 5, 2002

The Bilerico Project on LGBTQ Nation, “Larry Kramer’s Historic Essay: AIDS At 30,” June 14, 2011

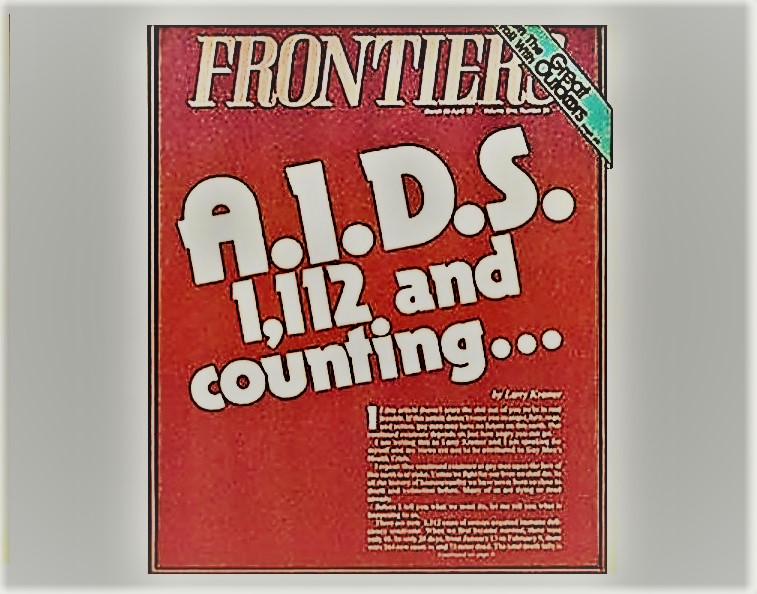

Los Angeles publisher Bob Craig publishes activist Larry Kramer’s essay “1,112 and Counting” in Frontiers magazine. Many of the gay bars where the free community magazine is distributed throw it out.

Learn More.First pubished in the March 14-27, 1983 edition of New York Native, Kramer’s long, comprehensive essay expresses frustration, anger and despair. A newcomer to the gay press, the bi-weekly news-magazine Frontiers gave the essay prominent placement on its cover.

After listing the names of 20 friends who had died of the disease (“and one more, who will be dead by the time these words appear in print”), Kramer closed with a plea: “Volunteers Needed for Civil Disobedience.”

By the end of 1983, 2,807 cases of (and 2,118 deaths from) HIV/AIDS had been reported in the U.S.

* * * * * *

Sources:

Los Angeles Blade, “March 27, 1983: 1,112 and Counting” by Larry Kramer, May 27, 2020

LGBT History Archives, “AIDS: 1,112 and Counting …” by Larry Kramer

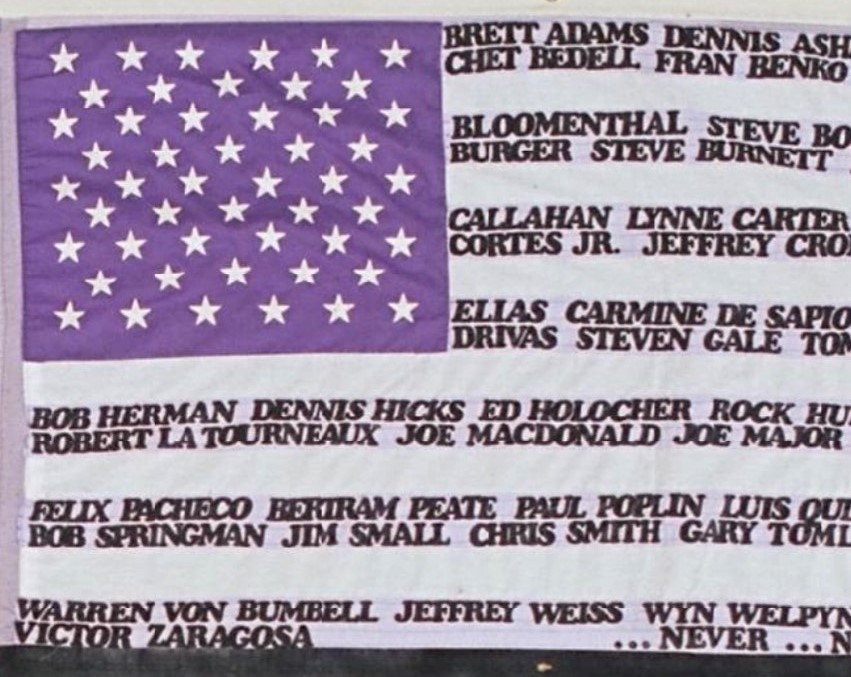

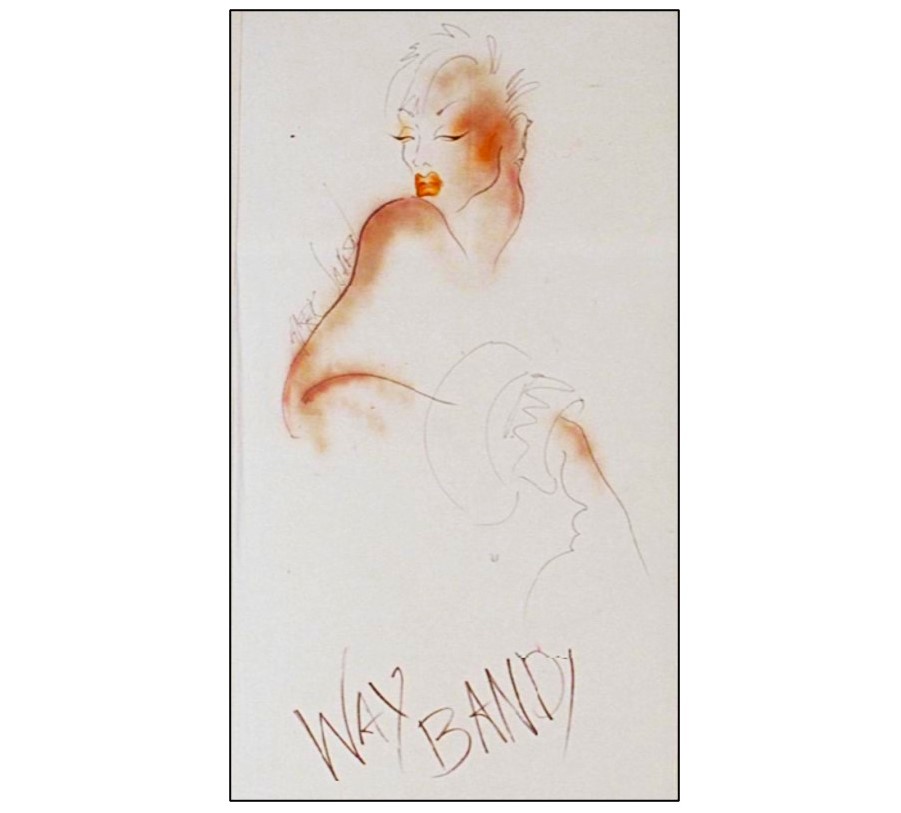

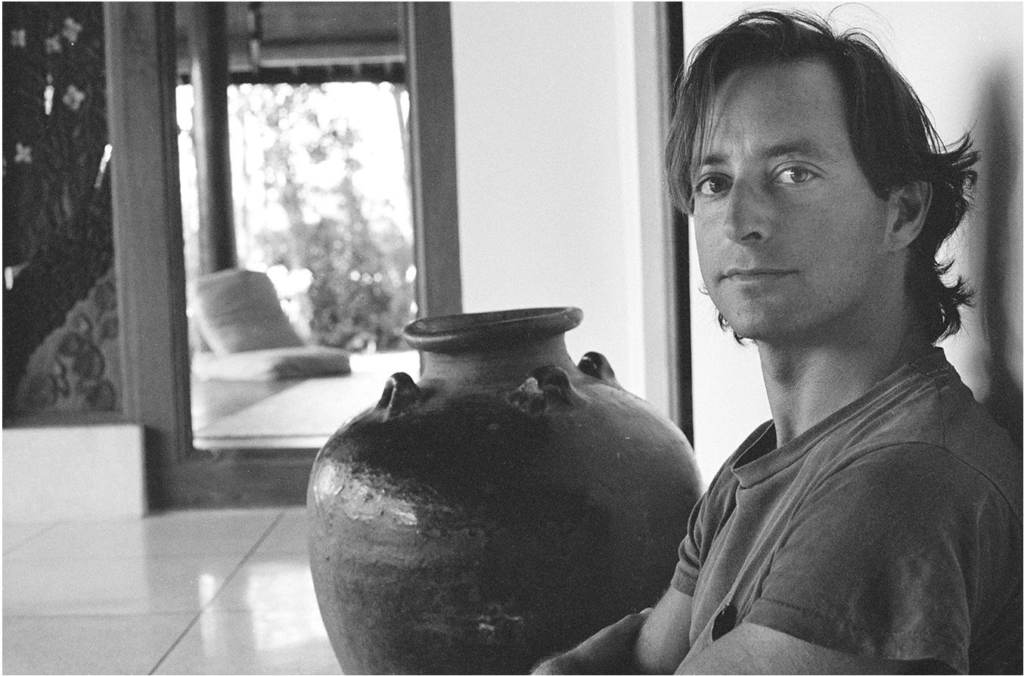

Joe MacDonald — the most popular male model of his time and a favorite photography subject of Andy Warhol and Bruce Weber — dies of AIDS-related illness in New York at the age of 37.

Learn More.Square-jawed and classicly handsome, he was frequently featured in GQ magazine during its Haber-Coulianos-Sterzin era, described by Meredith Etherington-Smith, who was GQ’s editor in the 1970s, as “so Zeitgeisty, in a tiny window of time when homosexuality was chic but not yet widely accepted.” Considered to be the first male supermodel, MacDonald counted David Hockney among his many friends and he enjoyed collecting art.

Friends were shocked to see how much MacDonald’s appearance had changed when his photo was featured in an early 1983 advertisement appearing in The New York Times fashion supplement, the results of MacDonald’s final modeling assignment.

“He looked very old,” Susi Gilder, a model who knew MacDonald personally, would tell New York magazine for an article published in June 1983. “The eyes were just very sad.”

In Vogue magazine’s 2020 retrospective on the AIDS crisis, fashion designer Michael Kors recalled MacDonald as the “first famous person who passed away” from AIDS.

“When we first started reading about [HIV/AIDS] and hearing about it, people did not want to acknowledge that this disease didn’t discriminate,” Kors told Vogue. “People thought, oh, if you’re young and you’re healthy and you, quote, live a clean life, you’re not going to get it. And then they started seeing people like Joe MacDonald and realized this was not selective. The reality became very harsh at that point.”

As the first AIDS casualty in the fashion industry, the news of MacDonald’s death sent shockwaves through New York.

“I remember walking in NYC on Columbus and 83rd – on the corner – one summer night,” model Rosie Vela told The AIDS Memorial on Instagram. “I passed Joe sitting at a crowded outdoors cafe. It was a year before he died.”

“He stood up when he saw me, and invited me to sit with him,” Vela recalled. “He was gorgeous, elegant and kind. I’ll never forget how welcome he made me feel. A true gentleman.”

* * * * * *

Sources:

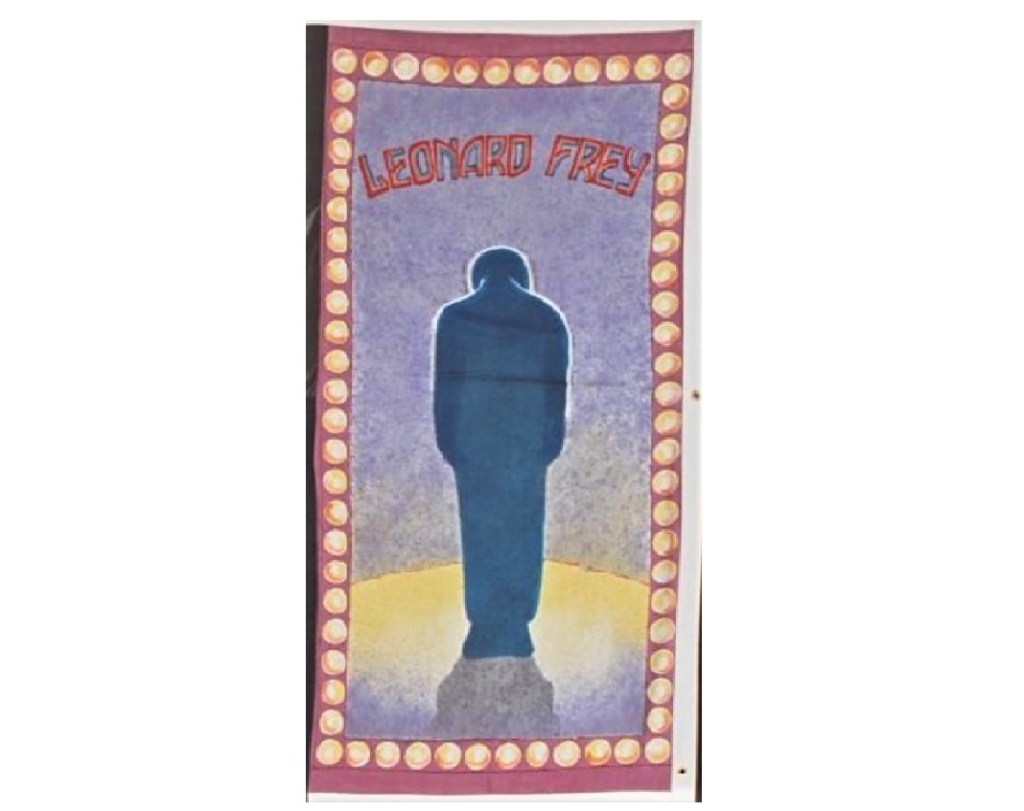

Photo of quilt panel from the AIDS Memorial Quilt

GQ magazine, “It All Started Here: The Gay Legacy of GQ” by David Kamp, June 23, 2017

New York magazine, “AIDS Anxiety” by Michael Daly, May 20, 1983

Vogue magazine, “Chapter One: How Fashion Was Forever Changed by ‘The Gay Plague’” by Phillip Picardi, December 16, 2020

The AIDS Memorial on Instagram, tribute post about Joe MacDonald

The news show 20/20 broadcasts the first investigative report on AIDS for network TV with reporter Geraldo Rivera.

Learn More.The 17-minute story features footage of hundreds of activists in AIDS memorial marches in San Francisco, New York City and Houston, as well as interviews with persons living with AIDS Ken Ramsaur, Bob Cecchi, Ron Resio, and Bill Burke

Reporter Geraldo Rivera charts the history of AIDS, starting with the first AIDS cases appearing in New York City and San Francisco in 1979 and the early occurances with members of the gay population, intravenous drug users, and Haitian immigrants.

For the story, Rivera interviewed several people from the front lines of the AIDS crisis, including Marcus Conant, M.D., of the University of California San Francisco Medical Center, who warns that the “entire American public” should be concerned about the disease. Dr. Conant tells Rivera that AIDS will become a major health crisis in the U.S. if research funds are not quickly allocated to develop effective ways to prevent and treat the disease.

“And so the evil genie is out of the bottle,” says Rivera, adding that AIDS has been diagnosed in 16 states already.

Rivera also interviews Larry Kramer, co-founder of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis in New York. In his characteristic animated fashion, Kramer criticizes The New York Times for failing to report on the AIDS crisis and expresses his frustration with the Centers for Disease Control for failing to add AIDS to its list of communicable diseases that public officials are required to report.

Rivera also includes footage of Rep. Henry Waxman in Congressional hearings, voicing criticism of the Reagan Administration for its lack of resources and action.

* * * * *

Source:

Vimeo | Lovett Productions, “20/20 AIDS Broadcast,” May 19, 1983

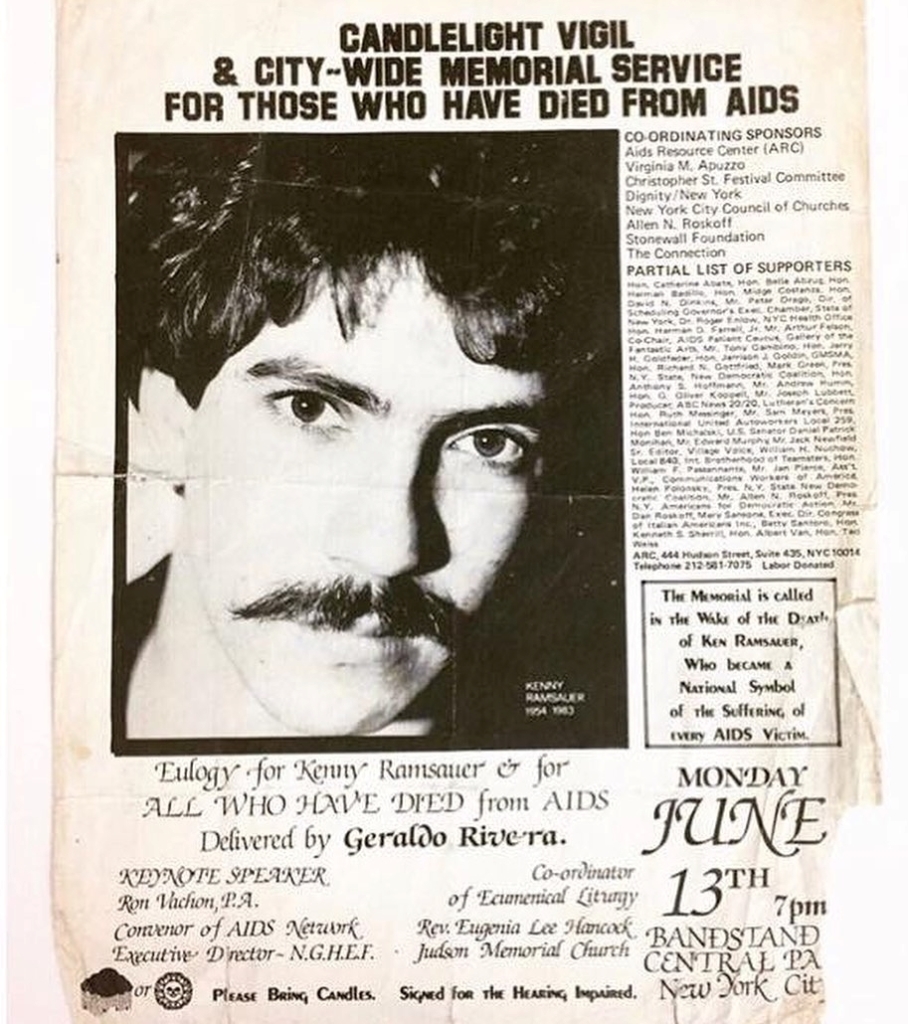

Ken Ramsauer, a businessman who was featured in reporter Geraldo Rivera’s investigative report for ABC’s 20/20, dies of AIDS-related illness in New York City. He was 29 years old.

Learn More.Ramsauer was a freelance lighting designer and hardware store manager who became the first person with AIDS to be the subject of a national television program when he was interviewed by Geraldo Rivera on 20/20.

His final televised wish was that people might gather in Central Park to remember those who had died of AIDS. The following month on June 13, more than 1,500 would gather in Central Park for a candlelight vigil to commemorate Ramsauer and others who died of AIDS. The event featured a eulogy by Rivera, a speech by New York Mayor Ed Koch, and a reading of the names of the 600 people known to have died from AIDS by that time.

”Kenny Ramsauer wanted the people of New York and of this country to learn about the disease,” Rivera told the people gathered at the park’s Naumberg Bandshell on that early summer evening. ”He wanted society to know the discrimination and negative publicity that has allowed this disease a mortal head start.”

The vigil was considered the first large gathering acknowledging the existence of the epidemic.

David France, author of How to Survive a Plague, attended the vigil with a friend and later wrote:

“The plaza was crowded with 1,500 mourners cupping candles against the darkening sky. As our eyes landed on one young man after another, it became obvious that many of them were seriously ill. A dozen men were in wheelchairs, so wasted they looked like caricatures of starvation. I watched one young man twist in pain that wsa caused, apparently, by the barest gusts of wind around us.”

Frances goes on to write that 722 cases of AIDS were reported in New York at the time, but judging from the scene around him, the numbers were likely considerably higher.

“We had found the plague,” he wrote.

* * * * * * *

Sources:

The New York Times, “1,500 Attend Central Park Memorial Service for AIDS Victim” by Lindsey Gruson, June 14, 1983

How to Survive a Plague by David France (MacMillan, 2017)

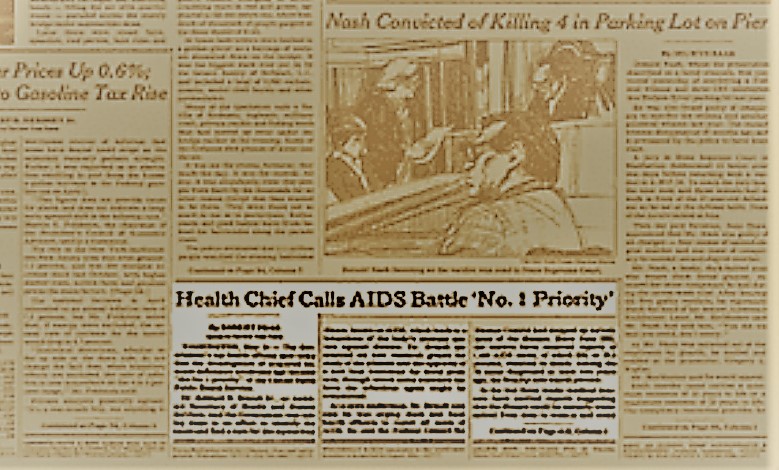

The New York Times publishes its first front-page story on AIDS, “Health Chief Calls AIDS Battle ‘No. 1 Priority’.” The article reports on the federal response to the growing AIDS epidemic.

Learn More.By the time the article reaches newstands, 1,450 cases of AIDS have been reported and 558 of those individuals have died.

Conservative televangelist Jerry Falwell, founder of the Moral Majority, tells his followers that “AIDS is not just God’s punishment for homosexuals, it is God’s punishment for the society that tolerates homosexuals.”

Learn More.A notious homophobe and segregationalist popular with religious conservatives, Falwell continues the campaign of stigmatization against the LGBTQ community that he began in the 1970s with Anita Bryant’s “Save Our Children” campaign.

The following month, Falwell’s organization, Moral Majority, would publish a report on AIDS titled “Homosexual Diseases Threaten American Families.” It featured a white couple with two young children, all wearing surgical masks, suggesting AIDS is a gay disease that can be spread casually. It also poses gay men as adverse to “families,” as if the two were mutually exclusive.

Many suspect that Falwell’s close ties to President Ronald Reagan directly contributed to the Administration’s refusal to address AIDS.

* * * * * *

Sources:

The Milford Daily News, “Press: The Sad Legacy of Jerry Falwell” by Bill Press, May 18, 2007

PBS, “Anti-gay Organizing on the Right” by Neil Miller (Out of the Past: Gay and Lesbian History from 1869 to the Present, Vintage Books, 1995).

American Historical Association, “Fearing a Fear of Germs” by Heather Murray, October 2, 2020

Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, “Moral Majority Report,” July 1983

Produced for a gay audience, I Will Survive is broadcast on Los Angeles public radio station KPFK 90.7 FM as part of a day of programming celebrating gay pride month.

Learn More.In the one-hour radio show, producer David Hunt examined “the conflicting currents of fear, greed, despair and denial that confronted the gay community in the early years of the AIDS epidemic.”

“For its time, the documentary is a fairly clear-eyed look at the emerging AIDS epidemic,” writes Hunt on his website Tell Me David. “It correctly emphasizes the medical consensus that a virus is the cause of the disease, and urges education, personal responsibility and collective action as the tools for fighting it.”

Hunt credits early activists with saving the lives of many people in the community in the early 1980s.

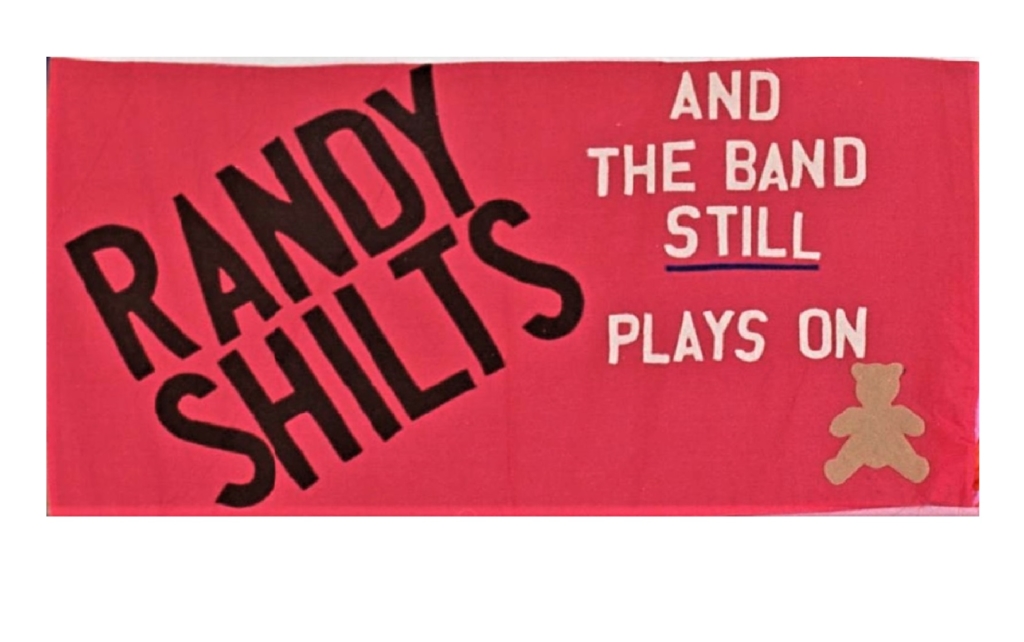

“Without the leadership of people like Larry Kramer, Randy Shilts, Harry Britt, Bobbi Campbell, Matt Redman and others, the suffering would have been far worse, the toll far greater,” he said. “I remember wondering in the early days, in 1981 and 1982, whether any of us would survive. Titling the documentary I Will Survive was an act of false bravado as much as it was a hat tip to Bobbi Campbell, who wore a button emblazoned with that message.”

* * * * * *

Source:

Tell Me David, “I Will Survive” by David Hunt, May 1, 2015

Metropolitan Community Church founder Rev. Troy Perry debates Moral Majority leader Jerry Falwell on the subject of “the AIDS controversy” on national TV.

Learn More.In the debate, Falwell calls for the mandatory closing of bathhouses, saying that AIDS is caused by homosexual promiscuity. Then he walks back his previous statement regarding AIDS as a punishment against homosexuality. He cites incorrect numbers regarding deaths and illness from AIDS.

The Rev. Perry responds, saying that diseases are the result of many variables, and that Falwell is dimishing the dangers of AIDS when he compares it with herpes. He goes on to tell the TV audience that the majority of members in the LGBT community are in loving relationships, and that is the norm.

The Rev. Perry founded the LGBTQ-inclusive Metropolitan Community Church in 1968 after recovering from an attempt to end his own life. He is well-known in the community for filing suit against the Los Angeles Police Department to clear the way for the city’s first Pride parade in 1970.

* * * * * *

Source:

Gay bars in West Hollywood and Los Angeles report a 20% drop in business, according to the Los Angeles Times. Six area bathhouses also report a 50% plunge in revenue.

Learn More.Some community members, like Circus Disco owner Gene La Pietra, think the drop may be related to an earlier news article that erroneously reported AIDS can be spread through casual contact.

* * * * * *

Source:

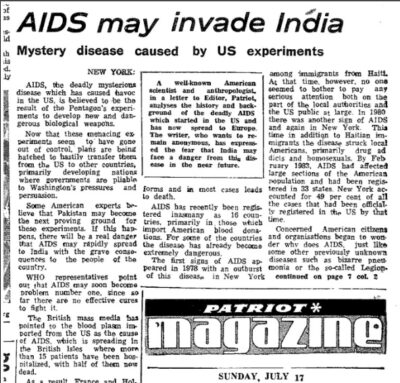

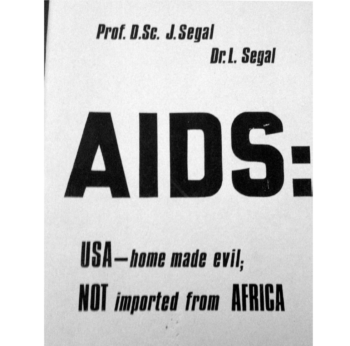

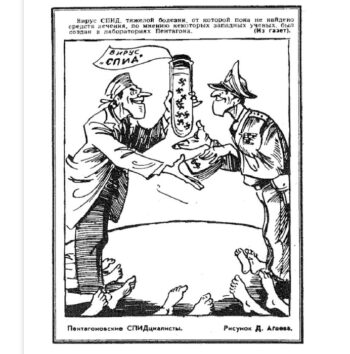

The Indian newspaper Patriot publishes an anonymous report claiming that the AIDS virus was created by the Pentagon as a potential biological weapon. The account, which was an entire fabrication, was part of a Soviet disinformation campaign.

Learn More.In a letter to the editor published on the front page of the Patriot under the title “AIDS May Invade India: Mystery Disease Caused by U.S. Experiments,” the writer cited the involvement of U.S. special services and the Pentagon in the appearance and rapid spread of AIDS.

The writer claimed to be a “well-known American scientist and anthropologist,” but in fact, the source of the account was a disinformation campaign led by the KGB, the foreign intelligence agency of the Soviet Union which was engaged in the “Cold War” against the U.S.

The Patriot was “a known front for KGB disinformation,” according to the Wilson Center, a U.S. organization dedicated to non-partisan counsel on global affairs.

The letter claimed that the AIDS virus was developed at Fort Detrick, an Army-run biological warfare laboratory located in Frederick, Maryland. Because the U.S. military was allegedly conducting experiments in neighboring Pakistan, the letter’s claims inferred that AIDS could soon spread to India.

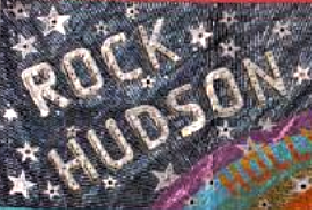

Rock star Jobriath dies of AIDS-related illness at the age of 36. He was the first openly gay pop singerto be signed to a major record label, and one of the first internationally famous musicians to die of AIDS.

Learn More.Born Bruce Wayne Campbell and raised in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania, Jobriath started his music career in the West Coast production of the musical Hair, receiving positive reviews in the lead role of Woof, a character implied to be gay. After leaving the production in 1969, he joined the folk-rock band Pidgeon as their lead singer and guitarist, followed by a two-album solo deal with Elektra Records in 1972.

His debut album Jobriath, released in June 1973, would feature an album sleeve design by photographer Shig Ikeda depicting a nude Jobriath as an ancient Greek statue. This photograph was used in an extensive publicity campaign for the album release.

Critical praise for the album followed the hype, and he was often compared with David Bowie, some critics contending that Jobriath had more talent than Bowie. But American music fans of the 1970s weren’t ready for a talent like Jobriath.

“At a concert at the Nassau Coliseum, chants of ‘faggot’ started from the minute he took the stage, along with rubbish thrown at him, and Jobriath was forced a flee the stage,” writes music historian Kevin Burke.

Elektra then rush-released Jobriath’s second album and ended its contract with him. Jobriath would spend the rest of the ’70s in a new identity, “Cole Berlin” (an amalgamation of Cole Porter and Irving Berlin), whose professions were nightclub signer and sex worker.

Jobriath had begun to feel ill in late 1981 but still managed to contribute to the Chelsea Hotel’s 100th birthday celebration in November 1982.

“A decade after his billboards hung in Times Square, Jobriath Boone died alone and abandoned in his rooftop apartment at the Chelsea Hotel,” Burke writes. “Sadly overlooking the New York skyline he once adorned, here his body lay decomposing for four days before it was found.”

* * * * * *

Source:

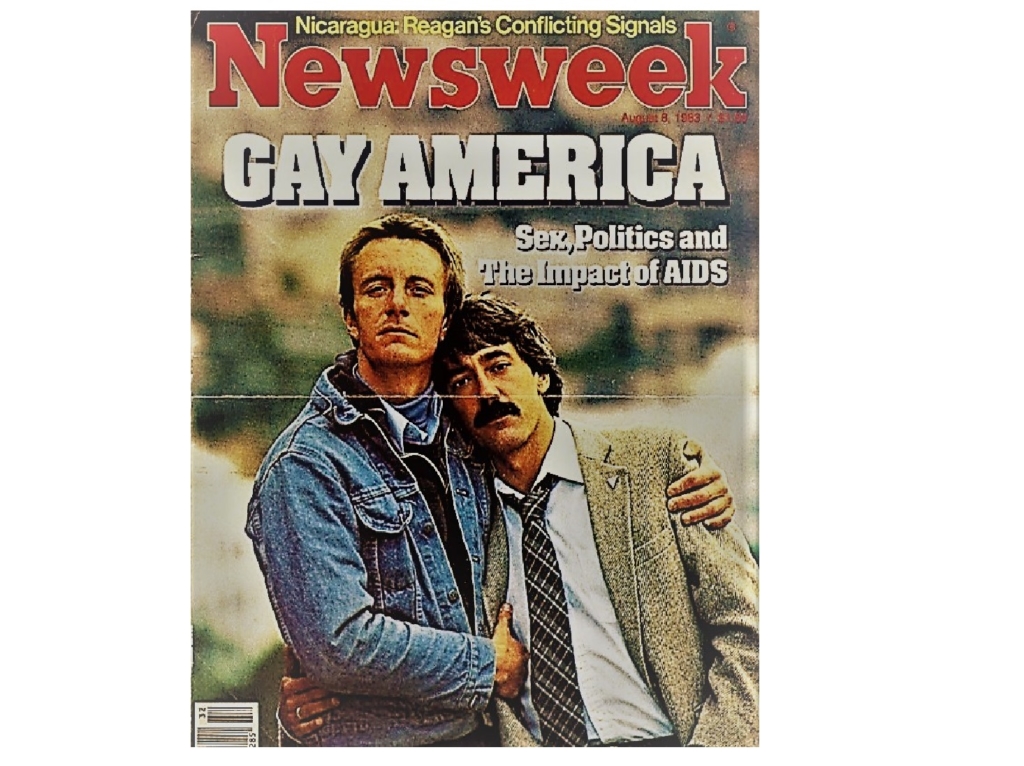

AIDS Activist Bobbi Campbell and his partner Robert “Bobby” Hilliard appear on the cover of Newsweek magazine for the story “Gay America: Sex, Politics and the Impact of AIDS.”

Learn More.Campbell and Hilliard’s appearance on Newsweek’s cover is the first time two gay men are pictured embracing one another on the cover of a U.S. mainstream national magazine.

But by this time, Campbell was accustomed to being covered by the media. He was the first person living with AIDS to come out publicly after he became the 16th person to be diagnosed with an AIDS-related illness in San Francisco, according to Back2Stonewall.

After he launched a column in January 1982 for the San Francisco Sentinel disclosing his Kaposi sarcoma diagnosis and describing his experiences as a person living with AIDS, he was often invited to speak at conferences and other events. When someone quipped that he was the “AIDS poster boy,” he embraced the characterization by putting it on a t-shirt in bold letters.

A registered nurse, Campbell joined the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, an activist performance group that uses drag and religious imagery to call attention to sexual intolerance, and took on the “sister” persona of Sister Florence Nightmare. He also co-authored the first San Francisco safer-sex manual, Play Fair!, which offered practical advice written in plain, sex-positive and often humous language.

Ever the prolific fighter for the cause, Campbell co-founded with another HIV-positive activist, Dan Turner, the People With AIDS Self-Empowerment Movement (or PWA Movement) in 1983. The movement promoted the right for those living with HIV/AIDS to “take charge of their own life, illness, and care, and to minimize dependence on others,” according to Back2Stonewall.

“The group had what then seemed like revolutionary ideas,” wrote Bill Lipsky, author of Gay and Lesbian San Francisco (2006). “It rejected the then-commonly used term ‘KS victim’ …

Almost a year after appearing on the cover of Newsweek, Campbell gave one of his last speeches at the National March for Lesbian and Gay Rights at the 1984 Democratic National Convention in San Francisco. Campbell told the crowd that he had hugged his boyfriend on the cover of Newsweek “to show Middle America that gay love is beautiful.”

Campbell died of AIDS on August 15, 1984. Hilliard died of AIDS a few months later.

In 2014, a Castro Street History Walk plaque was installed to commemorate Campbell and his work.

* * * * * *

Sources:

University of California Berkeley Library

University of California San Francisco Archives and Special Collections

Back2Stonewall

San Francisco Bay Times

Modern dancer Graham Conley, who performed with the Margaret Jenkins Dance Company, dies of AIDS-related illness at the age of 32.

Learn More.* * * * * *

Sources:

Photo of quilt panel from the AIDS Memorial Quilt

Bay Area Reporter, June 8, 2006

Comedian Eddie Murphy performs his comedy special “Delirious” on HBO with material that further stigmatizes gay men and HIV/AIDS. In the show, he makes jokes about AIDS, uses a gay slur multiple times, and tells the audience he is “afraid of gay people.”

Learn More.After its release to the public, the show would become watched by millions and go on to win a Grammy Award.

Murphy would apologize in 1996 for the homophobic remarks in his performances after gay rights activists in San Francisco mount a protest during one of his film shoots. In a public statement, Murphy said that he deeply regretted “any and all pain” that he caused, adding, “Just like the rest of the world, I am more educated about AIDS in 1996 than I was in 1981.”

David Smith, a spokesman for the Human Rights Campaign Fund in Washington, D.C., would respond: “This statement certainly does sound as though Murphy recognizes the impact his past statements have had on the gay community. It’s important for people in the public eye like Eddie Murphy to recognize they set a tone for the general public.

* * * * * *

Source:

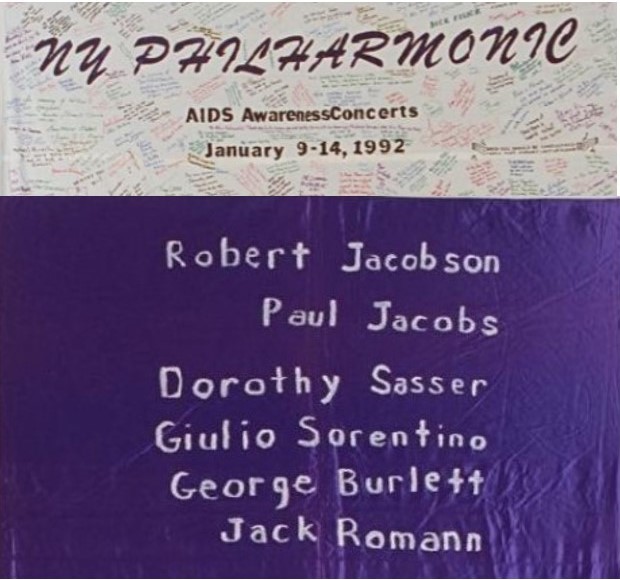

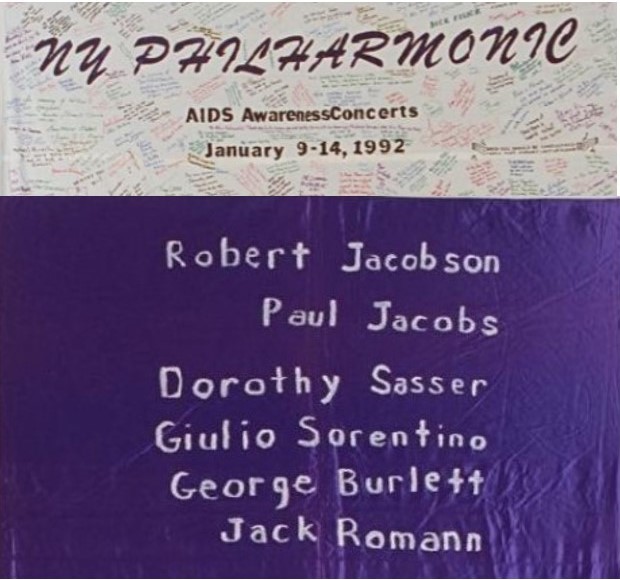

Paul Jacobs, the New York Philharmonic’s pianist and harpsichordist, dies of AIDS-related illness at his Manhattan home. He was 53.

Learn More.Paul Jacobs was the New York Philharmonic Orchestra’s official pianist and harpsichordist, holding the post during the tenure of three music directors, according to The New York Times.

He was best known for taking on “the more forbidding works of the 20th Century,” according to Lon Tuck of the Washington Post. He was also widely recognized for his expertise with early keyboards, often performing on harpsichord with Baroque ensembles.

Born in New York City, Jacobs studied at the Julliard School and then moved to France in 1951 to work with composer and conductor Pierre Boulez at Domaine Musical in Paris.

He returned to New York in 1960 to teach at the Manhattan Music School and the Mannes College of Music. Two years later, the New York Philharmonic named Jacobs its official pianist and, in 1974, harpsichordist.

He gave solo recitals and played frequently for Lincoln Center’s Chamber Music Society throughout the 1960s and 1970s. Jacobs recorded for several labels, including fifteen records for Nonesuch and a few for European labels.

For the last fifteen years of his life, he was Associate Professor of Music at Brooklyn College of the City University of New York.

In 1982, he was diagnosed with AIDS and informed he had only a few years to live. Faced with the decision of how best to use the months that remained to him, Jacobs decided to make one last record, which included the last compositions of Beethoven and Busoni and one of the last by Mozart.

Despite the deterioration of his eyesight, he managed to record the pieces, finishing the work in June 1983, about three months before he died. He completed the recording “on sheer determination,” Jacob’s doctor told Lon Tuck of the Washington Post.

About five months after Jacob died, on February 24, 1984, a memorial concert at New York’s Symphony Space drew the attendance of some of America’s most accomplished composers and musicians and many of his fans. The memorial program was tailored to reflect Jacobs’ musical tastes, according to Tuck. Composer Elliott Carter, the leader of America’s traditional musical avant-garde, delivered the eulogy.

* * * * * * * *

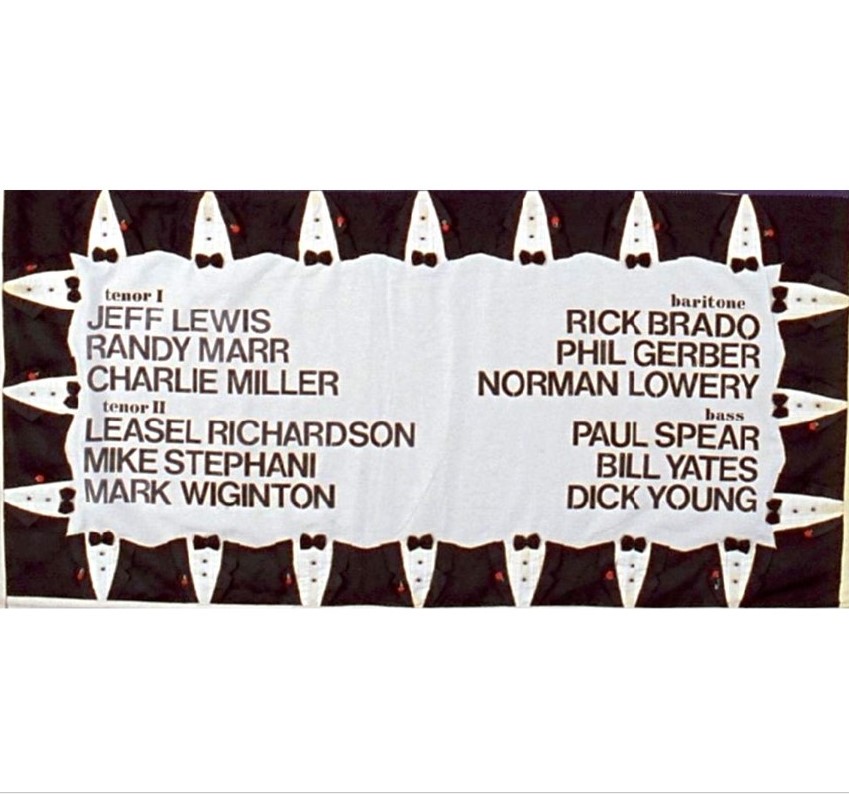

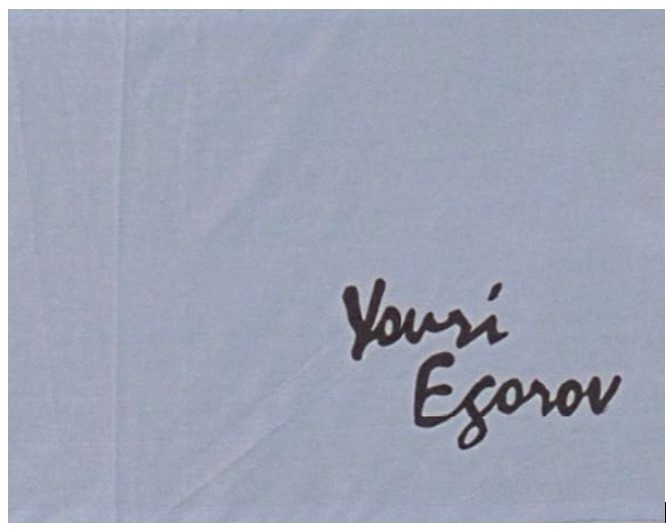

Photo of quilt panel from the AIDS Memorial Quilt

After New York City physician Joseph Sonnabend is threatened with eviction from his office building for treating patients with AIDS, the state’s Attorney General and Lambda Legal join together to file the first AIDS discrimination lawsuit.

Learn More.Dr. Sonnabend and five of his patients sued and won what became one of the first AIDS-related civil rights cases.

With others including AIDS activist Michael Callen, Dr. Sonnabend founded the AIDS Medical Foundation, the first AIDS research group and now known as the Foundation for AIDS Research.

* * * * * *

Source:

Russell Hartley, curator of the Archives of the Performing Arts, dies of AIDS-related illness in a San Francisco Hospital at the age of 61.

Learn More.In 1947, Hartley created the San Francisco Dance Archives, which is now known as the Museum of Performance + Design and includes 3.5 million items documenting the performing arts in the Bay Area.

By 1979, Hartley’s collection included 2,000 books, 8,000 periodicals, 4,000 slides, 5,000 negatives, 10,000 pieces of sheet music, 2,000 posters, 250 phonograph records, 25,000 historical photographs, 10,000 stills from the San Francisco Ballet, 10,000 movie stills, 12,000 theatrical prints, 500 artifacts, and 250 costumes, according to art critic Renée Renouf in Dance Chronicle.

“His unique confluence of personal artistry, a fund of personal anecdote and experience, and his single-minded devotion for the perpetuation of a collection commenced 40 years ago passes into its own special historical niche with Russell’s death,” Renouf wrote in 1983.

Born in 1924, Hartley attended Tamalpais High School in Mill Valley, California, which is located in the San Francisco Bay Area. Russell designed window displays for his father’s hardware store, according to the Museum of Performance and Design‘s Performing Arts Library. His artful window displays caught the eye of Ruby Asquith, a dance instructor who invited Hartley to visit the San Francisco Ballet studios and sketch dancers as they rehearsed.

Subsequently, he signed up for ballet classes and a year later, was given a part in Willam Christensen’s acclaimed production of Romeo and Juliet.

Early in his dance career, Hartley enjoyed success with the San Francisco Ballet in eccentric character roles between 1942 and 1949. In 1944, Christensen enlisted Hartley’s help in revising costume designs for Now the Brides, and this led to more significant work, including designing 143 costumes for the first production of the Nutcracker Suite in 1944, Pyramus and Thisbe, Coppelia, Swan Lake, Les Maitresses de Lord Byron, Jinx, Beauty and the Shepherd, and the Standard Hour television show.

Hartley’s art portfolio, Henry VIII and his Wives (1948), served as an inspiration for Rosella Hightower’s ballet by this name, which premiered in New York at the Metropolitan Opera House.

In the 1940s, Hartley became interested in collecting historical materials on local performers and dance and theatrical companies. He began combing antique stores for old dance and theatrical programs, photos, and ephemera, and these materials would become the start of his San Francisco Dance Archives.

In February 1946, Hartley, then almost 22 years old, and his friend Leo Stillwell, a 20-year-old artist, opened the Antinuous Art Gallery at 701 McAllister Street in San Francisco. Hartley began creating series of dance paintings and show windows in New York, leading to exhibitions of his paintings at the Feragil Galleries in New York, the Labaudt Gallery in San Francisco, and the Miami Beach Art Center, an exhibition on ballet at the De Young Museum, and features of his paintings in various one-man shows at galleries in San Francisco. Meanwhile, Stillwell worked furiously, creating 500 works of art before succumbing to an early death at the age of 22 following a case of measles.

Hartley carried on, executing costume designs for Balanchine’s Serenade, William Dollar’s Mendelssohn’s Concerto, Lew Christensen’s Balletino, and the San Francisco Opera Company’s productions of Aida and Rosenkavalier. He began studying the conservation of fine paintings with Gregory Padilla and carried out restoration projects for the Maxwell Galleries, the Oakland Museum, and Gumps. In 1960, he became a member of the International Institute for the Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works.

Dance Magazine hired Hartley to write a monthly column, which ran through the 1960s. He also contributed feature articles to After Dark Magazine, Opera and Concert, and The Trumpeteer.

He organized exhibitions on the history of the performing arts at the War Memorial Opera House and the main branch of the San Francisco Public Library with materials from his personal collection. In 1975, Hartley sought a permanent location for the Performing Arts Archive and was able to obtain a space in the basement of the Presidio Branch of the San Francisco Public Library.

His own archival collections, which had expanded to include materials on the history of the San Francisco Opera, San Francisco theaters, and the San Francisco Symphony, was supplemented by a dance library and other materials donated by local collectors. However, in 1981, budgetary cutbacks led to the closure of the archives and Hartley was forced to move the entire collection to his Mill Valley home.

At this time, Hartley’s health began to decline. In 1983, the archives were moved from Hartley’s home to the San Francisco Opera Chorus Room in the War Memorial Opera House and a Board of Directors was formed to ensure that Hartley’s legacy would carry on. Former San Francisco Ballet dancer Nancy Carter became the archives’ first executive director.

The archives are now known as the Museum of Performance + Design, which also serves as keeper of The Russell Hartley Collection, materials from Hartley’s early days as a costume designer for the San Francisco Ballet to his tenure as director of the Archives for the Performing Arts.

In 2016, the San Francisco Chronicle reported on the story of Alan Perry, a retired truck driver who found in a dumpster 200 letters written to Russell Hartley by his friend Leo Stillwell, the promising artist who died at the age of 22. Perry and his wife, who subsequently learned about Hartley and Stillwell and appreciated the cultural value of the find, donated the letters to San Francisco State University, where the prolific young artist’s 500 works of art are housed.

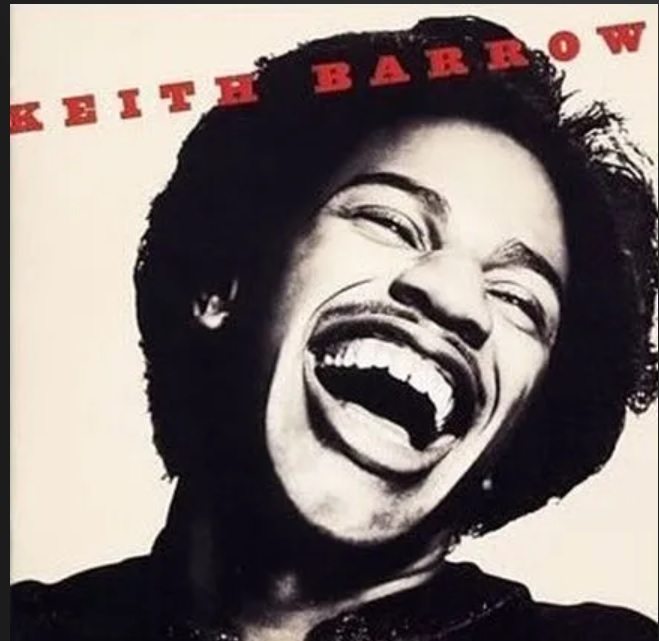

Keith Barrow, a singer and songwriter best known for the soulful “You Know You Wanna Be Loved” and the disco-beat-fueled “Turn Me Up,” dies of AIDS-related illness at Michael Reese Hospital in Chicago. He was 29 years old.

Learn More.The only son of Chicago civil rights leader Rev. Willie Barrow (1923-2015), Keith Errol Barrow started singing as a teenager with the gospel group “Soul Shakers.” His mother told Windy City Times in 2004, “Keith had music in his bones and in his soul. He started writing music when he was eight.”

After Barrow came out to his activist mother, she publicly embraced gay rights, according to The New York Times.

In 1973, Barrow released a self-titled gospel album at the age of 19 with Jewel Records, and his solo career began to gain traction with the popularity of one of the album’s singles, “Mr. Magic Man.” The major label Columbia signed him in 1976, and he left Chicago for New York and then Los Angeles. After a song he wrote for the Philadelphia R&B group Blue Magic rose in Billboard‘s Top 100 R&B hits, Barrow was invited to Philly’s famed Sigma Sound Recording Studios to work under legendary producer Bobby Eli for his first Columbia album.

The release of Barrow’s record was announced in a full-page ad in Billboard magazine for the week ending May 7, 1977. “Keith Barrow is why you should pay attention to this debut album,” the ad proclaimed.

“Though he’s not talked about much today, Keith was a true talent of his era, a singer’s singer whose velvety falsetto was on par with the finesse of Eddie Kendricks and the fancy of Sylvester,” wrote music critic S.E. Fleming Jr. in 2008. “When it was all said and done, Keith Barrow didn’t prove a huge hit, but it was a high quality effort that laid the groundwork for what would become his finest hour on record.”

Fleming says the best track on the album is Barrow’s performance of his own composition, “Teach Me (It’s Something About Love),” calling it “one of the most beautiful slow jams the singer ever recorded.”

“It was a perfect fit for a young man at a stage in his life where most people are finding their own voice, a lovely portrait of innocence and melancholy,” Fleming writes.

In 1978, Barrow switched to CBS Records, which produced his second album, Physical Attraction. Most of the material was co-written by producer Michael Stokes and songwriter Ronn Matlock, and they updated Barrow’s sound to include three disco songs.

Immediately, the seven-minute single “Turn Me Up” became a hit at dance clubs and broadened his fan base. Meanwhile, another song on the album, a smooth soul ballad titled “You Know You Want to Be Loved,” rose to #26 in Billboard‘s Top 100 R&B hits.

Barrow recorded a final album, moving to Capitol Records. Produced by Ralph Affoumado, Just As I Am (1980) was an ambitious work, but the dance sound that initially drew in fans was declining in popularity. Still, the album has a few gems, such as the seductive and funky “In the Light (Do It Better)” and “Tell Me This Ain’t Heaven,” which is reminiscent of some of his earlier work with Columbia.

Barrow tried to extend his career by performing live. While touring in Europe in 1983, he fell ill and called his mother, saying he was too sick to perform:

“He called me from Paris and said, ‘Momma, I don’t think I’ll be able to go on stage tonight. I really feel sick.’ I said, ‘Oh, you’ll be alright.’ I prayed for him and then he called again a couple of hours later and he said, ‘Momma, I can’t perform. I have to go; they have to take me to the hospital.'”

After returning to the U.S., Barrow moved back to Chicago and his mother tended to him as his health declined. After being admitted to Michael Reese Hospital, he was diagnosed with AIDS.

“I remember the first of the weekly reports that Keith was ill and the requests for prayers,” wrote Barrow’s childhood friend in 1007. “Keith’s mother is a fiery orator and fierce civil rights activist nicknamed ‘The Little Warrior,’ so it was hard to see her sadness and distress as his health declined.”

When Barrow died later that year, more than 1,000 people attended his memorial services. Barrow was one of the first people in the entertainment industry to die of AIDS, and the cause of his death was not reported in his obituary. But his mother openly talked about it in the years that followed, and she contributed a panel in memory of her son to the AIDS Memorial Quilt.

Stephen Lamb, a man living with AIDS who was profiled in a widely-read New York Times article, dies of AIDS-related illness at New York University Medical Center. He was 40.

Learn More.In a NYT article published in the December 5 issue on Page 1 of Section B, celebrated reporter Maureen Dowd chronicled Lamb’s final months.

Lamb, his body overwhelmed with cryptococcal meningitis, tuberculosis of the bone marrow, and an intestinal infection, had until recently lived on the upper east side of Manhattan and worked as a travel consultant.

One of the few visitors at Lamb’s hospital bed was William Carroll, a volunteer from the Gay Men’s Health Crisis who two months before had been assigned to be Lamb’s “buddy.” According to the NYT article, Lamb and Carroll found that they shared a love of literature, and in Lamb’s final weeks, Carroll often read to him from books of poetry by John Keats and Andrew Marvell.

“Bill and I have grown to like each other,” Lamb told the reporter four days before he died. “I just needed some companionship.”

Lamb’s death was the 514th AIDS-related fatality recorded by the City of New York. At the time, the Gay Men’s Health Crisis had provided services to 420 people with AIDS, and was facing a surge in their caseload, according to Dowd’s article.

The organization had been receiving about 50 new cases every month, but in November, they noticed a dramatic increase in the number of people with AIDS (PWAs) who needed help. Some were gay men, but there were also intravenous drug users who were heterosexual as well as people who had received tainted blood transfusions.

The GMHC was running 20 therapy groups, organizing its volunteer-run “buddy” program, and operating a 24-hour hotline which received an average of 1,200 calls every week, according to the article.

The organization’s volunteers, which then numbered about 200, did whatever was needed, from taking orange juice to homebound PWAs to serving as intermediaries with the city’s social-service agencies.

“They clean apartments, do laundry, make dinner, pick up prescriptions, mail rent checks, walk dogs, take their patients to doctor’s appointments, and simply keep them company,” Dowd reported.

Many of the volunteers, she wrote, had horror stories about the terrible treatment of PWAs.

“They tell of government clerks who neglect AIDS cases, because they are afraid to be in the same room to fill out forms. They tell of nurses and orderlies in hospitals who are so loath to enter the rooms of AIDS patients that they let the food trays pile up outside the door, leave trash baskets overflowing, or neglect patients lying in their own urine or excrement,” wrote Dowd.

One volunteer, Diego Lopez, told the reporter that he went to visit a dying patient in the hospital, and discovered him with blood seeping from his nose and mouth. When he asked a doctor to help the patient, the doctor handed him some gauze and told him to take care of it himself.

“I was shocked, but I did it,” Lopez said. “Afterward, I looked at my hands and there was blood all over them. I realized I had to start being more careful. But when you see a person dying, you don’t think about finding some gloves to wear.”

Dowd closed her article with a conversation she had with Larry Kramer, co-founder of Gay Men’s Health Crisis. Kramer told Dowd of how the AIDS crisis had deeply affected him. Already, 37 of his friends in New York were dead from the disease.

“I heard about Vinny on Saturday,” Kramer said. “Ron is a Black actor I know. Paul, a pianist. Gayle went to Yale with me. Ron Doud, the designer of Studio 54. Mark, I was involved with a long time ago. Peter, an architect.”

“Can’t something be done?” he asked, clenching a small green notebook he used to record the names of his dead friends. “The rest of the city, my straight friends, go on with life as usual — and I’m in the middle of an epidemic.”

NBC’s St. Elsewhere airs the episode “AIDS and Comfort,” with a story about a former councilman diagnosed with AIDS.

Learn More.In the episode, the presence of a person with AIDS at St. Elygius Hospital triggers the fears and prejudices of various hospital staff.

The episode attempts to call for compassion in its viewers while dispelling misinformation about the virus, using medical professionals as gateways to inform and educate a mainstream audience.

However, by depicting the patient with AIDS as a white, heterosexual, well-off character who is the victim of an ill-timed affair and the subsequent confusion about whether the patient is straight or gay once he is diagnosed, the viewers are presented with the message that “gay = AIDS,” reinforcing the stereotype stigmatizing the gay community.

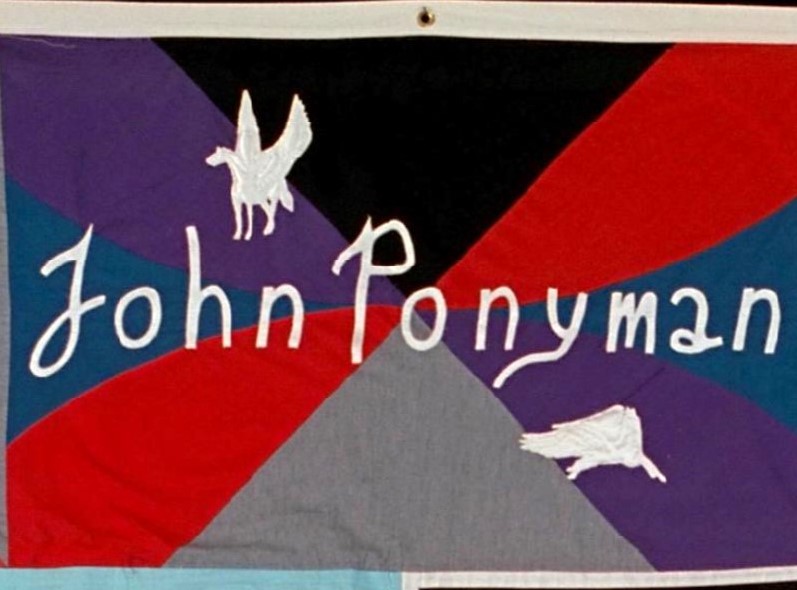

John Ponyman, an off-Broadway actor who migrated to San Francisco, dies of AIDS- related illness at the age of 41.

Learn More.Ponyman regularly appeared in shows at Theatre Rhinoceros. His final project was a solo show titled “Sawdust,” featuring several of his own songs.

* * * * * * * *

Photo of quilt panel from the AIDS Memorial Quilt

Philip Mandelker, who produced the television show The Dukes of Hazzard and 17 made-for-TV movies between 1974-1984, dies of AIDS-related illness in Los Angeles. He was 45.

Learn More.When Mandelker was diagnosed with AIDS in 1983, the first person he called was his friend Rob Eichberg, a Los Angeles clinical psychologist active in the LGBTQ+ community.

“His family was very dedicated to him and they insisted on people knowing Philip died of AIDS,” Eichberg told the Los Angeles Times.

“The day Philip died, I cried,” said Mandelker’s sister, Jane Makowka. “But I had cried my tears for months before. I knew a long time before anybody ever said it was AIDS that it was.”

Makowka said that her brother had a passion for living life to its fullest, which allowed him to bring a special quality to his television shows.

“Most important was his love of people and love of nature. He tried to bring that, something of quality to television, something people would remember,” she said. “He was very fortunate to have been as successful as he was in that short of a lifetime. You wonder what he might have done if it hadn’t been cut short.”

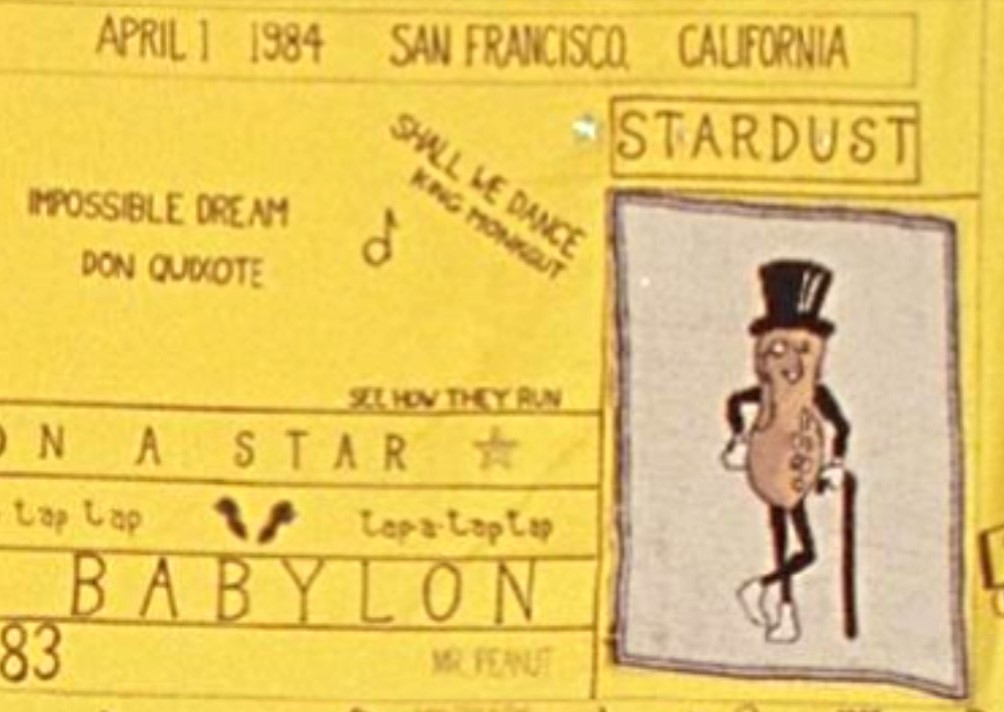

Performer Bill Kendall, who received rave reviews for his portrayal of “Mr. Peanut” in the long-running San Francisco production of Beach Blanket Babylon, dies of AIDS-related illness at the age of 35.

Learn More.

Beach Blanket Babylon was the world’s longest-running musical revue at the time. The show began its run in 1974 at the Savoy Tivoli and later moved to the larger Club Fugazi in the North Beach district of San Francisco.

Kendall was in the production’s original 1974 cast and continued to be a featured performer through 1982, playing the roles of Superman, John Travolta Sat Night Fever, and The Original Mr. Peanut.

Beach Blanket Babylon was created by Steve Silver, who died of AIDS-related illness in 1995. The San Francisco Chronicle described the show’s roots as a combination of “Vegas lounge acts, the Follies Bergere, God Rush-era extravaganzas, English music halls, a child’s birthday party gone mad and dopey beach party movies.”

* * * * * * * *

Photo of quilt panel from the AIDS Memorial Quilt

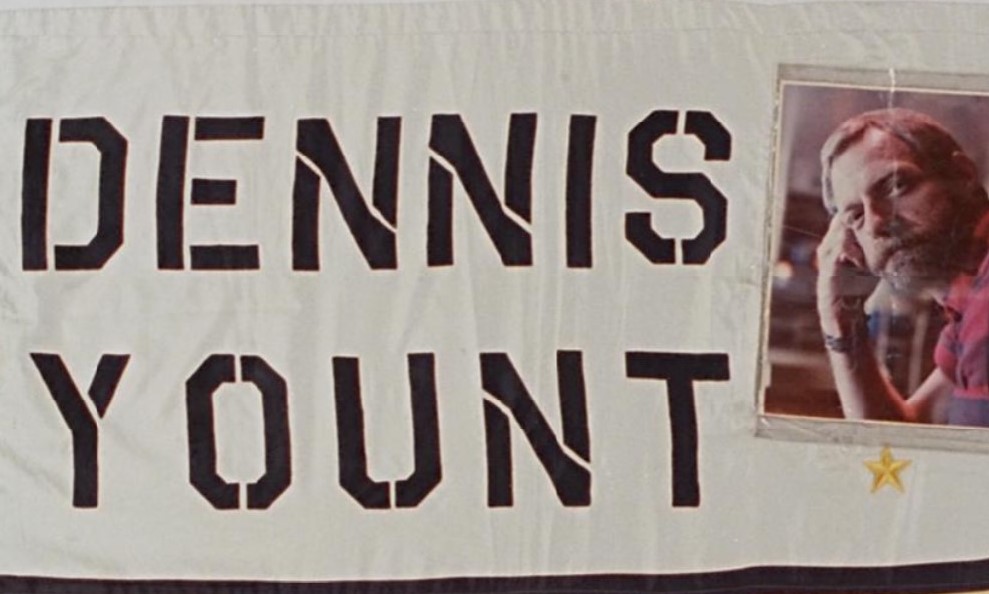

Dennis Yount, a Marine who served in the Presidential Honor Guard at President Kennedy’s bier in the Capitol Rotunda, dies of AIDS-related illness at the age of 43.

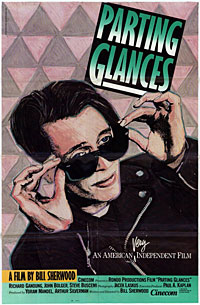

Learn More.Yount was born in North Carolina and attended North Carolina University at Columbia before joining the Marines. In 1970, he moved to New York City and became a favorite bartender at the Village bar Trilogy. He moved to San Francisco in 1980 and began tending bar at the Eagle.