Timeline

Dr. Friedman-Kien told New York magazine:

“In February 1981, I saw a young man who was perfectly healthy except for a number of spots on his skin. I’d never seen anything like it, so I did a biopsy. Under the microscope, the cell structure was clear: it was Kaposi’s sarcoma."

Dr. Friedman-Kien continued: “A week later, another physician sent me another patient, also a gay man in his late thirties, also with disseminated KS."

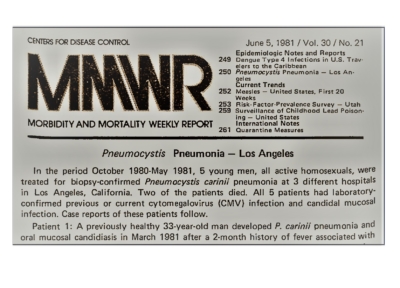

Later research would establish that AIDS-related KS is the second most common tumor in HIV patients with CD4 counts less than 200 cells, according to the NIH. Up to 30% of HIV patients not taking high-activity antiretroviral therapy (HAART) will develop Kaposi sarcoma. * * * * * Source: New York magazine, "Fighting AIDS" by Janice Hopkins Tanne, January 12, 1987 POZ magaine, "A Look Back at the Year a Rare Cancer Was First Seen in Gay Men" by Joseph Sonnabend, M.D., July 13, 2020 The New York Times, "Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals" by Lawrence K. Altman, July 3, 1981To coordinate the task force, the CDC selected James W. Curran, M.D., who would dedicate much of his life to HIV/AIDS research and would publish numerous research papers on the disease.

Task force members included David M. Auerbach, M.D.; John V. Bennett, M.D.; Philip S. Brachman, M.D.; Glyn C. Caldwell, M.D.; Salvatore J. Crispi; William W. Darrow, Ph.D.; Henry Falk, M.D.; David S. Gordon, M.D.; Mary E. Guinan, M.D.; Harry W. Haverkos, M.D.; Clark W. Heath, Jr., M.D.; Roy T. Ing, M.D.; Harold W. Jaffe, M.D.; Bonnie Mallory Jones; Dennis D. Juranek, D.V.M.; Alexander Kelter, M.D.; J. Michael Lane, M.D.; Dale N. Lawrence, M.D.; Richard Ludlow; Cornelia R. McGrath; James M. Monroe; David M. Morens, M.D.; John P. Orkwis; Martha F. Rogers, M.D.; Wilmon R. Rushing; Richard W. Sattin, M.D.; Mary Ellen Shapiro; Thomas J. Spira, M.D.; John A. Stewart, M.D.; Pauline A. Thomas, M.D.; and Hilda Westmoreland.

In its first year, the Task Force on Kaposi’s Sarcoma and Opportunistic Infections received case reports from the following doctors working in New York, San Francisco and Los Angeles:Donald F. Austin, M.D.; Erwin Braff, M.D.; James W. Buehler, M.D.; James Chin, M.D.; J. Lyle Conrad, M.D.; Selma Dritz, M.D.; Diane M. Dwyer, M.D.; Shirley L. Fannin, M.D.; Yehudi M. Felman, M.D.; Stephen M. Friedman, M.D.; Robert A. Gunn, M.D.; John P. Hanrahan, M.D.; Robert J. Kingon, M.D.; Michael D. Malison, M.D.; Stanley I. Music, M.D.; Mark A. Roberts, M.D.; Alain J. Roisin, M.D.; Richard B. Rothenberg, M.D.; and R. Keith Sikes, M.D.

* * * * * Sources: National Institutes of Health, "In Their Own Words ... NIH Researchers Recall the Early Years of AIDS" Frontline | PBS, "Interview: Jim Curran," interviews conducted Jan. 18, 2005 and Feb. 15, 2006 The New England Journal of Medicine, "Epidemiologic Aspects of the Current Outbreak of Kaposi's Sarcoma and Opportunistic Infections," January 28, 1982

"The reporting doctors said that most cases had involved homosexual men who have had multiple and frequent sexual encounters with different partners, as many as 10 sexual encounters each night up to four times a week.

"Many of the patients have also been treated for viral infections such as herpes, cytomegalovirus and hepatitis B as well as parasitic infections such as amebiasis and giardiasis. Many patients also reported that they had used drugs such as amyl nitrite and LSD to heighten sexual pleasure.

"Cancer is not believed to be contagious, but conditions that might precipitate it, such as particular viruses or environmental factors, might account for an outbreak among a single group."

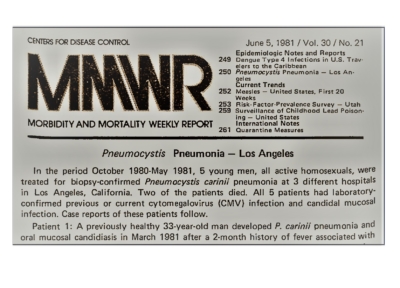

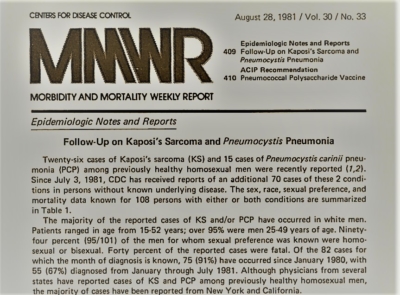

According to Dr. Joseph Sonnabend, a New York City clinician who was among the first in the U.S. to recognize the emerging AIDS epidemic, this article was significant because of the Times' large, international readership. But doctors treating New Yorkers from the gay community had been noticing strange symptoms and unusual illnesses in their patients for at least two years. "I had been observing some clinical and laboratory abnormalities among my patients as early as 1979. These included enlarged lymph glands, an enlarged spleen, low blood platelets and a low white blood cell count," Dr. Sonnabend told POZ magazine in 2020. "Then, in April or May of 1981, I was stunned to learn that Kaposi’s sarcoma was being diagnosed in young gay men in New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco. Joyce Wallace, a physician whose office was close to mine on West 12th Street in New York passed this information on to me," he recalled. When Dr. Sonnabend heard about the KS cases in young men, he reached out to a colleague, Dr. Alvin Friedman-Kien, a dermatologist at NYU medical center. Dr. Friedman-Kien was caring for several gay men with Kaposi’s sarcoma, and soon Dr. Sonnabend joined him at NYU's virology lab. Through their research, the doctors found high levels of interferon in their patients. Early research and discoveries like this formed the foundation of HIV/AIDS research for many years to come. * * * * * Sources: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), "Kaposi's Sarcoma and Pneumocystis Pneumonia Among Homosexual Men — New York City and California," July 3, 1981 The New York Times, "Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals" by Lawrence K. Altman, July 3, 1981 POZ magazine, "A Look Back at the Year a Rare Cancer Was First Seen in Gay Men" by Joseph Sonnabend, M.D., July 13, 2020 POZ magazine, "Interferon and AIDS: Too Much of a Good Thing" by Joseph Sonnabend, M.D., May 7, 2011

"At that point in time, not many people knew about this problem, and it wasn't getting a whole lot of attention," Dr. Groundwater later recalled for the San Francisco AIDS Oral History Project. "I don't think the seriousness of it was widely appreciated -- the potential for major problems in the future."

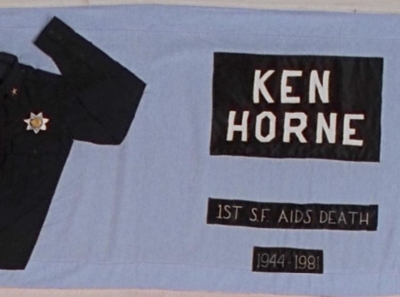

Dr. Groundwater said he wrote the copy for the brochure and used photographs of a patient's KS lesions so dermatologists could see how the disease manifested. The patient was Ken Horne, the first KS case to be reported to the Centers for Disease Control. Horne had died on November 30, 1981, just days before the conference. * * * * * Source: University of California Libraries, "The San Francisco AIDS Oral History Series | The AIDS Epidemic in San Francisco: The Response of Community Physicians, 1981-1984," interview with James R. Groundwater, M.D., conducted by Sally Smith Hughes, Ph.D. in 1996

"He was fascinating even as a small child," his mother Ann Harris told The New York Times Magazine in 2003. "All the other kids followed him and acted out his fantasies. He did Camelot one time and had the kids on bicycles with the handlebars as the horses' heads. Another time he directed Cleopatra, and used the garden hose as the serpent and our cats as Cleopatra's gifts to Caesar. He was very much the little producer."

When his family returned to New York in 1964, George Jr. reprised the El Dorado Players, augmenting the troupe with children he met in Greenwich Village. He took acting and singing classes at Quintano's School for Young Professionals, and soon he was cast as an extra in a milk commercial, a deaf-mute in a television series and an antiwar protester in an Off Broadway play called Peace Creeps, co-starring Al Pacino and James Earl Jones.

The latter role would be strangely prescient. On October 21, 1967, an 18-year-old George Jr. would be photographed placing a flower in a gun barrel pointed at him while taking part in an anti-war demonstration at the Pentagon. The photo, widely circulated in the media, became iconic of the anti-war movement and generational divide in the country.When some members of The Cockettes began insisting that they begin charging for their shows, Hibiscus refused and found himself expelled from the group he founded. Unperturbed, Hibiscus formed a new theatrical group called the Angels of Light Free Theater. Their shows included Flamingo Stampede and The Moroccan Operette, which Hibiscus described as being ''like Kabuki in Balinese drag.''

Among the people he convinced to perform with the Angels of Light was poet Allen Ginsberg, who appeared in drag for the first time. Hibiscus found another collaborator in his new boyfriend, Jack Coe, also known as Angel Jack, who eventually moved to New York with Hibiscus in 1972, around the same time that the Cockettes disbanded.

Upon his return to NYC, he recruitd his mother and three sisters (Jayne Anne, Eloise and Mary Lou) into an east coast version of the Angels of Light. “I wrote almost all the music for the Angels of Light,” said his mother, Ann. “George would say, ‘Oh, I need a sheik scene, with a sheik in it,’ and then I would come up with a song.”The group performed at the Theatre for the New City, where John Lennon was known to jump on the stage and sprinkle glitter on Hibiscus.

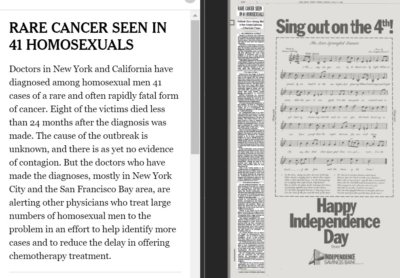

In the early 1980s, he and his sisters and brother formed the glitter rock group "Hibiscus and the Screaming Violets," supported by musicians Ray Ploutz on bass, Bill Davis on guitar and Michael Pedulla on drums. But he had to stop performing in 1981 due to his escalating illness.It's testament to the power of his personality and creativity that the spirit of Hibiscus dominates the 2002 Cockettes documentary, even though the film's focus is on the group. Decked out in gender-bending drag and tons of glitter, the flamboyant ensembles of both The Cockettes and Angels of Light are considered to be the inspiration for later theater productions like The Rocky Horror Picture Show and acts like The New York Dolls.

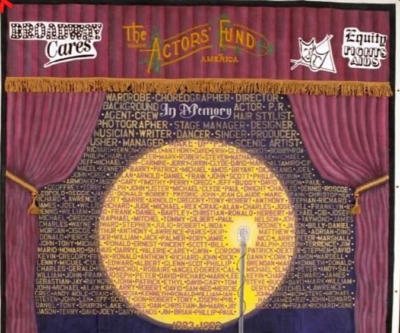

* * * * * * Sources: Photo of quilt panel from the AIDS Memorial Quilt- An estimated 185,000-415,000 homosexual males lived in LA County in 1982.

- If one assumes each homosexual male in LA County has between 13 and 50 different sexual partners per year during 1977-1982, "the probability that seven of 11 patients with KS or PCP would have sexual contact with any one of the other 16 reported patients in LA County would seem to be remote."

- With this same assumption, "the probability that two patients with KS living in different parts of Orange County would have sexual contact with the same non-Californian with KS would appear to be even lower."

- Thus, observations in LA and Orange counties imply the existence of an unexpected cluster of cases.

Born in 1945 in the Wales town of Haverfordwest, Higgins left for London as a teenager. He worked as a reporter for Hansard, the House of Commons' official record, and in the evenings as a nightclub barman and DJ. In the late 1970s, he would often travel to work in New York and Amsterdam.

In 1980, he was forced to put his traveling on hold due to persistent and, at the time, unidentifiable illnesses. In the summer of 1982, he collapsed while at work at the Heaven nightclub in London and was hospitalized. Soon after, he died of the AIDS-related illnesses Pneumocystis pneumonia and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy.

-

- Extraordinary care must be taken to avoid accidental wounds from sharp instruments contaminated with potentially infectious material and to avoid contact of open skin lesions with material from AIDS patients.

- Gloves should be worn when handling blood specimens, blood-soiled items, body fluids, excretions, and secretions, as well as surfaces, materials, and objects exposed to them.

- Gowns should be worn when clothing may be soiled with body fluids, blood, secretions, or excretions.

- Hands should be washed after removing gowns and gloves and before leaving the rooms of known or suspected AIDS patients. Hands should also be washed thoroughly and immediately if they become contaminated with blood.

- Blood and other specimens should be labeled prominently with a special warning, such as "Blood Precautions" or "AIDS Precautions." If the outside of the specimen container is visibly contaminated with blood, it should be cleaned with a disinfectant (such as a 1:10 dilution of 5.25% sodium hypochlorite (household bleach) with water). All blood specimens should be placed in a second container, such as an impervious bag, for transport. The container or bag should be examined carefully for leaks or cracks.

- Blood spills should be cleaned up promptly with a disinfectant solution, such as sodium hypochlorite (see above).

- Articles soiled with blood should be placed in an impervious bag prominently labeled "AIDS Precautions" or "Blood Precautions" before being sent for reprocessing or disposal. Alternatively, such contaminated items may be placed in plastic bags of a particular color designated solely for disposal of infectious wastes by the hospital. Disposable items should be incinerated or disposed of in accord with the hospital's policies for disposal of infectious wastes. Reusable items should be reprocessed in accord with hospital policies for hepatitis B virus-contaminated items. Lensed instruments should be sterilized after use on AIDS patients.

- Needles should not be bent after use, but should be promptly placed in a puncture-resistant container used solely for such disposal. Needles should not be reinserted into their original sheaths before being discarded into the container, since this is a common cause of needle injury.

- Disposable syringes and needles are preferred. Only needle-locking syringes or one-piece needle-syringe units should be used to aspirate fluids from patients, so that collected fluid can be safely discharged through the needle, if desired. If reusable syringes are employed, they should be decontaminated before reprocessing.

- A private room is indicated for patients who are too ill to use good hygiene, such as those with profuse diarrhea, fecal incontinence, or altered behavior secondary to central nervous system infections. Precautions appropriate for particular infections that concurrently occur in AIDS patients should be added to the above, if needed.

- 1980

- 1981

- 1982

- 1983

- 1984

- 1985

- 1986

- 1987

- 1988

- 1989

- 1990

- 1991

- 1992

- 1993

- 1994

- 1995

- 1996

- 1997

- 1998

- 1999

- 2000

- 2001

- 2002

- 2003

- 2004

- 2005

- 2006

- 2007

- 2008

- 2009

- 2010

- 2011

- 2012

- 2013

- 2014

- 2015

- 2016

- 2017

- 2018

- 2019

- 2020

- 2021

- 2022

- 2023

- 2024

- 2025

- 2026

- 2027

- 2028

- 2029

- 1980s

- 1990s

- 2000s

- 2010s

- 2020s