Stories of Strength

Norm and Louis and the Chelsea Gym

Story & Recording by Ken Gault

On August 9, 1987, Norman Rathweg died of AIDS.

Somewhere in the 1980s, gay bars — especially in the Village — were going out of business. Perhaps it was the dying clientele, perhaps it was part of the global growth of health-culture, but the bar was being replaced by the gym as the place to meet, to hook up, or both.

Norm and his partner, Louis, were catching this wave of change. They opened the Chelsea Gym at the corner of Eighth Avenue and 17th Street, the middle of the new gayborhood. The entrance was on 17th Street, lockers on the ground floor, showers and steam room downstairs, weights, machines and mirrors upstairs overlooking Eighth Avenue.

We came to the gyms to gain, lose, socialize or lurk. For some, it was a competition to look fabulous and ‘get’ whatever there was to be ‘gotten,’ especially if it meant themselves. The buff-bodies paid little attention to me. Or if they did I was oblivious. Like everyone else, with or without the virus, I battled my own feelings of inadequacy.

There was something else going on with these men and their bodies. Those pounds of muscle said to the world that this bad-ass body does not, cannot, will not have AIDS. That might happen to someone else, but not to me, not to this body.

And there was something deeper and even more subtle. These walls of muscle were built for protection, to keep others out and most painfully, to keep feelings from getting in. The intimacy that was nearly impossible in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s, became deadly in the ’80s. Perhaps the paths are clearer now, but even so, but still its difficult to navigate physical and emotional intimacy.

For some, they are one in the same. Physical intimacy equals emotional intimacy. For others, sex cannot and should not coexist with emotion. Sex is, well, just sex. For most, the grey area remains unambiguously grey. What is true for one is not necessarily true for the other. What is true in one moment, may not be true in the next.

Maybe its easier now, and men are more successful at it. Writing on intimacy will take time and will likely make me very unpopular. Stay tuned.

In the end, having a great body is its own reward, the by-product of a healthy life-style, feeling alive, working out the frustrations of the day with iron plates or a stair-master and modulating those endorphins.

In any event, Norm and Louis were there, on the second floor overlooking the iron plates, the cables, machines and sweating bodies. Aside from the leather jackets and Harleys, they looked to me like any other men running a successful business. Had they been straight, they might have been in the Lions Club.

I found out much later that Norm was more than a successful businessman. Earlier in his career, he designed two of the most iconic holy grails of sex, drugs and Rock ’n Roll that brought gay men to New York in the first place.

In City Boy, Edmund White says this:

“Norm … ‘a part-time beau’ … designed the St. Mark’s Baths and ‘the Hindenburg of discos,’ The Saint. Seemingly a prototype of the muscular gay males who would come to rule Chelsea, he grew up a bookish nerd in Florida, where his invalid father ‘would lie in bed drinking and insulting his big, fearful, skulking son, calling him a creep and a faggot.’”

Who knew? I guess everyone knew, except me.

The last time I saw them, I was in line to board the ferry to Fire Island. They were resting from the 20-foot walk from the boat. I went to say hello.

Norm looked up. His face was blank and poorly shaven. He tried to speak but all that came out was a raspy groan. Louis smiled and did the talking.

In a moment, I was back in line to the ferry. Louis was helping Norm into a medical transport van.

Howard Ashman, 1950-1991

Recording by Alan Menken

Story by Irwin M. Rappaport and Alan Menken

Howard Ashman was a masterful writer, lyricist and director, in my opinion the greatest of our generation, who died of AIDS on March 14, 1991, at the age of 40. My name is Alan Menken. In a collaboration that lasted 12 years, Howard and I wrote the stage and movie musical Little Shop of Horrors and won two Academy Awards, two Grammy Awards and three Golden Globe Awards for Little Mermaid, Aladdin and Beauty and the Beast.

We forged a collaboration that was intense, creative and supremely effective. Each moment I spent in the creative space with Howard Ashman remains with me every day of my life.

With our first project at Disney, Little Mermaid, some studio executives resisted using the song “Part of Your World,” for fear we would lose some of the younger audience members. But Howard insisted that our audience had to know what our little mermaid Ariel wanted. She needed to have what he called an “I want” song.

I think that as a gay man, Howard grew up knowing what it felt like to be on the outside, wanting to be a part of the world that he saw around him but somehow not able to fully take part.

For two years, while Little Mermaid was being made, Howard knew he had HIV but he hid his illness from everyone on the movie, including me. We found out later that, during the press junket for Little Mermaid at Disney World in Orlando, Howard wore a catheter in his chest so that he could get medicine intravenously at night. When he saw the parade of Little Mermaid characters at the park, he burst into tears.

Later, those of us who worked with Howard realized why he cried: It was the idea that those characters would live on long after he was gone.

The night we both won our Oscars for Little Mermaid, Howard said he and I needed to have a serious talk, and after we got back to New York, Howard revealed to me that he was sick with AIDS. We had just reached the pinnacle of our careers in both theater and the movie business, and we had worked side-by-side for 11 years, yet my dear friend kept it a secret from everyone he worked with that he had an incurable fatal disease. That’s the kind of fear people lived with back then: fear of rejection, of death, of a fatal illness with no cure, and there was so much stigma and discrimination.

But Howard wouldn’t let AIDS keep him down. He was so determined to keep working, to keep creating magical song moments and unforgettable characters. I think AIDS spurred him on to work even harder because he knew he was living on borrowed time.

Howard and I were brought in to fix Beauty and the Beast while it was being developed. But Howard was too sick to commute back and forth to LA, so he finally had to tell Jeffrey Katzenberg that he had AIDS. Katzenberg agreed that the production would travel from LA to meet with Howard and me in upstate New York.

At the same time, we were also working on Aladdin, which Howard had initially developed. Because of AIDS, Howard was suffering neuropathies, began losing feeling in his fingers, losing his voice and much of his eyesight, all the while we were collaborating on joyous, incredible songs. Howard was determined to keep working as long as he could.

Towards the end of his life, Howard and I wrote “Prince Ali” from his hospital bed. He was down to 80 pounds. He couldn’t see and could barely speak.

Howard and I won an Oscar for Best Song for Beauty and the Beast. And the movie was the first animated picture ever nominated for Best Picture. Howard had passed before ever experiencing the movie’s success. The award was accepted by his companion of seven years, Bill Lauch.

Daniel Warner (1955 – 1993)

Story & Recording by Mark S. King

It wasn’t easy keeping my composure when I interviewed for my first job for an AIDS agency in 1987. Sitting across from me was Daniel P. Warner, the founder of the first AIDS organization in Los Angeles, LA Shanti. Daniel was achingly beautiful. He had brown eyes as big as serving platters and muscles that fought the confines of the safe sex t-shirt he was wearing.

I’m Mark S. King, a longtime HIV survivor.

At 26 years old, with my red hair and freckles that had not yet faded, I wasn’t used to having conversations with the kind of gorgeous man you might spy across a gay bar and wonder plaintively what it might be like to have him as a friend. But Daniel did his best to put me at ease. He hired me as his assistant on the spot, and then spent the next few years teaching me the true meaning of community service.

As time went on, Shanti grew enormously but Daniel’s health faltered. He eventually made the decision to move to San Francisco to retire, but we all knew what that really meant. I was resigned to never see him again.

In 1993, Shanti hosted our biggest, most star-studded fundraiser we had ever produced. It was a tribute to the recently departed entertainer Peter Allen, lost to AIDS, and the magnitude of celebrities who came to perform or pay their respects was like nothing I have ever seen. By that time, I had become our director of public relations, and it was my job to corral the stars into the media room for interviews.

Celebrities like Lily Tomlin, Barry Manilow, Lypsinka, Ann-Margret, Bruce Vilanch, and AIDS icon Michael Callen were making their way through the gauntlet of cameras to the crowded media room. And then one of my volunteers approached me with a look of shock and excitement on his face. He pulled me from the doorway.

“I didn’t know he was going to be here,” he said with wide eyes. “I mean –“

“Who?” I asked. Oh my God. Tom Hanks? Richard Gere?

“He’s with Miss America, Mark,” he said. “They’re right behind me.”

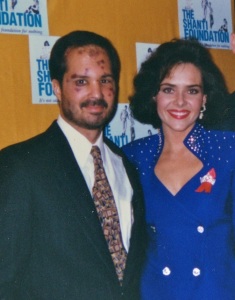

We both turned as the couple rounded the corner of the hallway. They entered the light of the media room and I barely kept a gasp from escaping.

Beautiful Leanza Cornett, who had been crowned Miss America, in part, by being the first winner to have HIV prevention as her platform, had a very small man at her side. His head bore the inflated effects of chemotherapy, which had apparently done little to stem the lesions that were horribly visible across his face, his neck, his hands. His eyes were swollen nearly shut. In defiance of all this, his lips were parted in a pearly, shining smile that matched the one worn by his gorgeous escort.

I stepped into the media room, wanting to collect myself, to wipe the look of pity off my face. I swallowed hard and stepped into the doorway to announce them to the press.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” I said. “Miss America 1993 Leanza Cornett, escorted by Mr. Daniel Warner, co-founder of the Los Angeles Shanti Foundation.”

“Ladies and gentlemen,” I said. “Miss America 1993 Leanza Cornett, escorted by Mr. Daniel Warner, co-founder of the Los Angeles Shanti Foundation.”

The couple walked into the bright light and several flashes went off at once. And then the condition of Miss America’s companion dawned on the camera crews. A few flashes continued, slowly, like a strobe light, and across the room a few of the photographers lifted their eyes from their equipment to be sure their lenses had not deceived them.

Daniel looked to me with a graceful smile, and it became a full, sunny grin as he looked to the beauty queen beside him and put his arm around her. She pulled him closer to her. Their faces sparkled and beamed – glorious, joyful, defiant – in the blazing light of the room.

That man, I thought to myself, that brave, incredible man is the biggest star I have ever seen.

And then the pace of the flashes began to grow as the photographers realized they were witnessing something profound. The couple walked the path through the room and toward the other door.

“Just one more, Mr. Warner?” one suddenly called out.

“Miss America! Just another?”

The room became a cacophony of fluttering lenses and calls to look this way and that, all of it powered by two incandescent smiles.

Daniel and Leanza held tight to each other, their delight lifted another notch as they basked in their final call. Every moment of grace, every example of bravery and resilience I have known from people living with HIV, can be summed up in that glorious instant of joy and empowerment.

“Boss,” I said to him as they exited the room, “I didn’t know you would be here. It’s just… so great.”

He winked at me.

“I’ll be around,” he said. “I brought my whole family with me tonight. I need to get to the party and show off my new girlfriend!”

The three of us laughed, and then I watched Daniel and Miss America, arm in arm, disappear down the hall and into the reception.

Only months later, I received a phone call.

“Mark, this is Daniel,” said a weakened voice. “Monday is my birthday, and I thought that might be a good day to leave.”

Daniel had always been fiercely supportive of the right of the terminally ill to die with dignity and on their own terms. We shared some of our favorite memories of our days at Shanti, and I was able to thank him for his faith in me and setting into motion a lifetime of work devoted to those of us living with HIV.

Daniel P. Warner, as promised, died on his birthday on Monday, June 14, 1993. He was 38 years old.

* * * * *

This story is an edited version of the essay “The Night Miss America Met the Biggest Star in the World,” which Mark S. King published in March 2015 on his website, My Fabulous Disease. Photo credit: Leanza Cornett and Daniel Warner by Karen Ocamb.

Pride Tirade 2021

Story and Recording by John Kelly

Happy as I limp my wrist in pride for us — the outcast, the maligned, the persecuted, the entrapped, the murdered, the sweated, the followed, the avoided, the violated, the blackmailed, the serial-tattooed, the sneered, the ostracized, the erased, the hated, the invisible, the raped, the tolerated, the patronized, the parodied, the joke, the denigrated, the evicted, the diminished, the emasculated, the de-promed, the expelled, the therapized, the shock-treated, the lobotomized, the numbed and the drugged, the lost, the dead, the erased, the removed from tangible history, the persistent dwellers in blessed proximity, the survivors, the warriors, the steadfast, the persistent, the inclusive, the non-ageist, the color blind, the expansive, the essential, the imaginative, the true, the warriors, the activists both stewing and shout spewing, the long term survivors demanding to be honored, the generational glue that is gold, the striving and striding toward our place in the sun that demands to be respected, and the imperative that we acknowledge that the AIDS pandemic ruptured our inter-generational dialogue, and our personal, systemic, collective and more generally cadenced growth.

This/MY generation of artists — and OUR audiences — disappeared.

YOU are standing on our generational, grave–like, culturally curtailed, and tribally intrinsic sinkhole. You may be afloat and faring ok on the gravitas of a vast family of ghosts and heart shattering loss, of dead young unresolved spirits. Advance, as we had done, in your own way and manner, and as you continue to grow and transform the world, please aim to bless the ground on which you re-trace our analog step.

WE walk the very same path.

A Mother’s Unconditional Love

Story & Recording by Aaron Holloway

I never even told my mother I was gay and she didn’t know. While lying there in what I perceived to be my deathbed, I thought that my mother would abandon me. She never did.

I was a graduating senior at Prairie View A&M University in Texas and on my spring break visiting my mother when I was diagnosed with AIDS and end-stage renal failure. When I arrived home, I was greeted very warmly by my mom. Her retirement party was that night. Over the weekend, my health continued to deteriorate. On March 10, 2008, the anniversary of my father’s passing four years prior, my mom insisted on taking me to the emergency room. She drove us to the hospital, where I was born and where my father passed away. I was beyond terrified.

After check-in and having my vitals taken, the nurses began taking several laboratory tests. Within 24 hours, I was checked into the hospital and had an AV fistula implanted into my heart. I was diagnosed with end-stage renal failure. The nephrologist assigned to me was shrewd and proclaimed that my kidneys were “gone” and I would never urinate again.

The same general physician I saw previously in the presence of my mother informed me about my AIDS diagnosis, and thereby outed me — twice. I will never forget what that physician said to me.

“Wake up! It’s AIDS. Are you surprised?”

Miraculously, during one of my dialysis treatments over that summer, my kidneys regained their proper function. I was able to return to my undergraduate studies.

In May 2009, I graduated cum laude from Prairie View A&M University with Bachelor of Business Administration in Management degree. I also graduated cum laude from Texas A&M University – Commerce with a Master of Science in Technology Management degree.

Spared, Blessed and Fully Awake

Story by Alexandra Billings

When it happened it was not a surprise. It was not out of left field and it was not unexpected. When it happened it was happening to everyone. Everyone I knew. Everyone around me. A black curtain had been thrown over the heads of us all and smothered us all in a cloud of decaying flesh and bloodied foot prints.

And the stench of the AIDS virus infiltrated the inside of my being and it is still potent. It is still thriving. Because I still have AIDS.

And I have outlived most everyone I knew, and we were in our 20s and we were in our 30s and we were still young and still having sex and still doing drugs and still running and jumping and skipping and singing and being queer. And yet one by one, we were being ticked off like ducks at a carnival. In the heart. In the brain. In the limbs.

And for some unknown reason . . . some of us were spared. And it is daily. And it is not gone. And it is getting worse. And it is still potent and it is still fresh. And it still lives in me and one day it will kill me. I know that.

But I am here and I am present and I am fully awake. And I love my life and I am married to the greatest human on the planet and I have spirits around me that bathe me in light.

And so I am truly blessed. Not that I have this disease, but that I learn from it. I remember very well when it happened. Because it seems like it happened yesterday.

West Hollywood Aquatics 1982

Story and Recording by James Ballard

There are not a lot of us left who were there at the beginning of West Hollywood Aquatics in 1982. Our numbers have grown thin, especially for those of us who seroconverted in the early days of what was then was called the gay plague. My name is James Ballard, and I am one of those survivors.

I am blessed with the remembrances of a team that used joy, compassion, courage, and love to fight against a virus that silently spread for years before it was given a name and started taking lives. This is our history as I know it.

Our team was first known as West Hollywood Swim Club, but in many aquatic circles we were dismissed at the onset as “that fag team.” Back then, abuse at meets was not whispered, it was shouted — at least until the races ended and the results were posted. No, we didn’t win every race, but we won more than enough to make it hurt, and we wanted to make it hurt every time another team called us out for being gay.

Looking back, I’d say we found a fair amount of joy in being aggressively gay, because we were building more than a team. We were building pride and an environment where no one need apologize for living out loud. That light still shines.

It would be years before we zeroed in on National and World Masters records, but we could see the possibility, if only we could stay in the water and stay alive. You see, at the beginning, none of us knew that our world had already changed, that a virus was taking hold of our lives. Colds grew into pneumonia, what seemed like bruises became Kaposi sarcoma, and fear spread. There was no test to detect the virus.

We had been working out at E.G. Roberts, a Los Angeles city pool on Pico Boulevard where we had a permit, but our eviction came without notice. The pool manager didn’t want us spreading our disease even though no one knew how it spread or even what caused the disease.

It was like facing a tidal wave in the dark. We lobbied LA City Hall and the LA County Supervisors with very limited success. We took workouts where we could find them, moving from pool to pool. We were constantly searching.

Where could our openly gay team find workout space, and how much chlorine would be dumped into the pool before we walked on deck?

We were rarely welcomed, and we wondered whether our team would survive. November 29th, 1984 changed that. West Hollywood incorporated into an independent city and the next year we were given a home in the old pool that lived below where STORIES: The AIDS Monument now stands. Yes, the pool deck was cracked and the tile needed repair, but it didn’t matter. It was our home and with every lap, we sang a little louder and prayed a little harder.

To us, the space where the AIDS Monument now stands will always be sacred. The smiles and the talent and the souls that lifted us up live on here, and I see the tall bronze Traces as spires rising from the light in the water that connected us with hope and the strength to swim the next mile and believe tomorrow was possible.

By the time we moved to the old pool in West Hollywood Park, we knew it was a virus. Medical researchers, however, offered no promise of a treatment.

The disease was relentless. We grieved and we cried as we said goodbye to the teammates we loved. There was no reprieve as the virus continued to take its toll. The grief overwhelmed us as we wondered who would be next. Most of us knew we could be next. No one felt safe, but in diving into the water we could escape and feel the beauty of living.

It became our freedom. Swimming was living.

We started reading the names of those we lost at swim meets, but those lists were always incomplete. So many simply disappeared. We hoped they had gone home to be with family, but we knew that home was a door that would never open for so many. And year after year, we read more names and remembered.

The lessons we learned was we had to form our own family because who else would understand? We did not turn away, and through it all, new members stepped up. The gay male team gave way to the team of everyone. It was magical. We lived with acceptance, and those who joined gave us hope and proved that change was possible.

Now four decades later, we have not lost the faith. We swim in a new pool that has a view of the bronze Traces, and we know they will carry the light of our team into the heavens. We will not forget. We are West Hollywood Aquatics.

Peter Grant

Story & Recording by Danny Lee Wynter

“Christy Turlington’s legs are the bees knees” he said flicking through my mum’s copy of Vogue. I’d never seen anyone like him. Exquisitely dressed, Peter Grant, my mother’s childhood friend arrived in my life when I was 8. A time I was terrified of being me. I was aware of him throughout my childhood. I didn’t really know him but I knew how he made me feel. Awkward. Embarrassed. Brimful with self loathing. Peter was what kids today describe as a ‘femme queen.’ And every inch of him denoted his right to be so.

I heard little about Peter in the intervening years. Then one day I overheard my mum saying he had AIDS. The news paralysed me. At 11, it was something nobody in my surroundings was sympathetic to. I learnt of Peter’s death while in the midst of experiencing the routine humiliations of a young homosexual in high school. The skirting about the issue of why you don’t have a girlfriend. The shame of the changing rooms during games practice and feigning asthma attacks to be excused. When Peter died I was still denying the biggest part of me which only came to life in the art rooms or choir practice.

Peter’s funeral took place where he died, the London Lighthouse. I was asked to sing at the service. Hesitant at first, I made the connection as to why I’d been so scared of him. I felt I owed him an apology, so I sang Barbra Streisand’s ‘The Way We Were’ accompanied by the piano. There surrounded by his lover, family, friends and the staff who cared for him, I encountered for the first time a tribe unlike any I’d ever come into contact. I was 13. At one point my mum points to a severely handsome man sat holding his boyfriend’s hand. He was as ‘masculine’ as any man I grew up with. ‘That’s Guy!’ my mother’s friend whispered, ‘I wish he was my Guy!’ mum replied, my tiny frightened childish mind blown.

Years later I would come to experience the gay community’s own deep and complex relationship with the performance of masculinity and the chastising of those deemed ‘too femme’ or too much like Peter! I think back to the scared little boy who met him and now know you can’t ever be too much of yourself. Peter taught me that.