Stories of Inspiration

Lulu & Her Fairy Godfathers

Story & Recording by Lulu from San Francisco

When I was a little girl, we rented out a room in our large Haight-Ashbury flat to generate extra income. It was always rented to a young gay man, probably because my mum, a single parent, felt it was the safest and most sensible option.

Their room was right next to mine in the front of the house and included a sitting room that we called the “library,” because it had floor to ceiling bookcases, big puffy pillows on the floor and comfy nooks to settle in for reading or taking a nap. It was a common area in the house, but was mainly for our renter’s use, though I could often be found perched on the big overstuffed chair, peering out the window to observe the view of the always entertaining corner of Haight and Ashbury Streets.

If I wasn’t daydreaming, I had my nose buried in a book; such is the life of an only child in a household with no TV. Inevitably, our housemate would slide open the French doors that divided their room to the library and slowly, gently, tenderly, carefully, our friendship would unfold.

The men who lived with us all referred to themselves as my “fairy godfathers” – their term, not mine. As a child, I didn’t understand the tongue in cheek we’re-taking-our-power-back meaning. Once I did, I both grimaced and grinned.

We had about five young men live with us over the years. This was in the late ’70s – early ’80s, before gay people could easily adopt kids or were even really allowed to think, dream about becoming parents in some cases. I was the only child in their circle of friends and was often invited to tag along to their ever so glamorous soirées, Oscar parties, holiday fêtes, and any other over-the-top event that might just really be a Tuesday night but always seemed like so much more. These outings gave my mum nights off from mum-ing and me, adventures to be fondly remembered decades later.

I often found myself sitting crossed-leg in the middle of one of their friend’s exquisitely decorated antique-filled living rooms in the Castro district on a priceless oriental rug, beading necklaces or playing with antique paper dolls (theirs, not mine), Judy blasting in the background, watching a group of lively young men gossip and flirt and dance and share stories about their hopes, dreams, and fears.

I heard them talk about how they had escaped to San Francisco from places like Iowa, Kentucky, Texas, so that they could live and love freely. They had all been disowned by their families for being gay. They had to create their own families, and I was privileged to play the role of the little sister, niece, cousin they had to leave behind or, on an even deeper level, the child they never believed they would ever be able to have. It was from them that I learned my lifelong mantra: Friends are the family we choose for ourselves. And love is love.

Sorry, Lin, but they said it first.

Of course, I was much too young to really understand the implications of all of this, but what I did know was that I felt so grown up and cherished in their presence.

I knew there was something special about these men. To me they were worldly and fancy and sparkly and they knew a little something about everything. And most importantly, they taught me what they knew.

From them, I learned about music and fashion and art and literature and Broadway and why black and white movies of the ’40s were the best movies and that you must always bake with butter, never margarine and that cookie dough is calorie-free and the power of the LBD and that one must always dress up when going downtown and the difference between Barbra Streisand and Barbara Stanwick, Bette Davis and Bette Midler, Oscar the Grouch and THE Oscars, and the importance of wearing sunglasses, even in the fog, to prevent wrinkles, darling.

They were men of great style, class, elegance, intellect, wit, charm, creativity, beauty and fun. They were incredibly cultured and had exquisite taste. My memories of my time with them run deep:

– Going to the “Nutcracker” every Christmas Eve

– Having high tea at Liberty House

– Lip syncing and dancing to the Andrew Sisters “Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy” (I know all the words still, to this day)

– Taking in the Christmas decorations downtown at Macy’s and I.Magnin’s, and ending the day with a cable car ride to Ghirardelli Square for hot chocolate with extra cherries and whipped cream

– Lengthy sermons on the essential need for dust ruffles and monogrammed stationery and silk dressing gowns

To a young child, these experiences leave a mark, a permanent flourish of rainbow-colored glitter sprinkled on her soul.

To my child’s eye, mind and heart, these men were magical. They were my playmates, the most delightful big brothers to a shy, often sad and lonely little girl. They were fun and silly and played dress up and always let me be Cher to their Sonny – a major sacrifice on their part, to be sure!

They told me I was a glittering gem and that I was “fabulous” and they meant it in a REAL way, not a “hey girl hey” way, though we had those moments, too.

They treated me with respect. They didn’t patronize or pander to me. They expected me to keep up my end of the conversation, regardless of the topic or my lack of knowledge about it. Local politics or Best Dressed at the Oscars, my opinion mattered to them.

They didn’t baby me. They treated me like an equal. But that didn’t mean that they didn’t spoil and coddle me. They made me feel special and valued and respected. Perhaps because society didn’t offer them the same respect as gay men, they felt compelled to make sure I was always treated as a whole person.

For a young girl of color, this went far in developing my sense of self and worth and pride in being who I was.

They also showered me with gifts, some that I still have to this day:

– A beautiful hand-woven throw made on an old-fashioned loom

– A hand-beaded necklace with an antique tiny bell at its center (too tiny now for my adult neck but still cherished)

– A beautiful white cake stand from Tiffany’s, an odd gift for a 10-year-old girl, you might think, but as the gift giver said when he handed me the HUGE blue box, “Sweetie, if I’ve taught you nothing else, please remember this: The light blue box is always the BEST box!”

I still have those treasures, but I no longer have my fairy godfathers.

They all eventually succumbed to AIDS. They were all in long-term relationships. Their partners died, too. By the early ’90s, they were all gone.

These men were the first and most prominent adult male figures in my young life; in truth, the only father figures I had growing up. I know for a fact that it is because of my time with them that I am the person, the woman, the friend, the activist, I am today.

They didn’t live to see the many strides and advances that the LGBTQ community has made. If they were still alive today, they would be at the front of the line continuing to fight the good fight for the strides still to be made.

But they aren’t, so I do it for them. It is the least I can do to honor their legacy and repay them for all they have given me.

My description of these men might seem almost disrespectful in its seemingly stereotypical depiction of gay men, but these were the men I knew, as I knew them, when I knew them. This was who they were, at a time when the gay community in San Francisco was thriving and carefree, when the pulse of the disco beat of the day seemed to ring in sync with the beat of the cultural awakening that was taking the world by gloriously gay rainbow storm on the streets of San Francisco.

I am so lucky that I spent my formative years as their fairy goddaughter, wrapped up in the glow of this historical time. But my golden carriage turned into a pumpkin well before midnight of my young adulthood dawned and my fairy god-fathers vanished with it.

I am a better human being because I knew them. THIS, I know for sure.

My fairy godfathers may be gone, but their rainbow-colored fairy dust flows in my veins forever.

They had their Pride. And they gave me mine, too.

Love,

Lulu

Elizabeth Glaser, 1947–1994

Ariel Glaser, 1981-1988

Story & Recording by Jake Glaser

“My life had certainly not turned out the way that I expected, but while tomorrow would bring what it would, today was glorious.”

– Elizabeth Glaser, wife, sister, mom and angel

On a Los Angeles summer night, in a chance meeting at a stop light on Sunset Boulevard, Elizabeth Glaser, a second grade school teacher, and Paul Michael Glaser, a television star from Starsky & Hutch, rolled down their car windows and found one another on this spinning rock in the cosmos to create a family whose creation, passion, love, fear, tragedy and sacrifice would change the world.

It was in 1981 when my mother, Elizabeth Glaser, gave birth to our guardian angel, our guide in life, Ariel. While in labor at Cedars Sinai in Los Angeles, my mother hemorrhaged and lost seven pints of blood. In order to save her and her baby, a blood transfusion was necessary, one that would forever change the path of their lives. What began as new virus predominantly showing up in gay men, the Human Immunodeficiency Virus was spreading fast and amongst many communities, not just the homosexual community.

My sister Ariel became sick. She would sink into sickness one week and bounce back the next, signs of what most called an extreme flu, but became known soon after as the global health crisis we now know as AIDS.

It was soon after this that I was born, HIV positive and with an unknown future. After years of antibiotics, and medications never designed for the fragility of a child’s immune system, my sister’s HIV turned into AIDS and took my sister’s life at age 7.

A mother’s response to losing her child is like a crack of thunder across the world. My mother knew she lived with this same virus, and so did I. Her only choice was to do something about it. So she asked for help, used her skills of getting people to come together and work together, and applied it to the start of the Pediatric AIDS Foundation, in an effort to raise essential funds for medical research into pediatric treatments for HIV.

She smashed down politicians’ doors, called Hollywood to action with my father, raised the funds, and built a team of interdisciplinary medical researchers to start asking questions to which we did not have the answers. She used every last bit of her energy to humanize this issue, speaking at the 1992 Democratic National Convention, advocating in Washington, and telling her story to the world in hopes of bringing enough light to this dark place so our future could be bright.

In 1994 after witnessing the creation of the first antiretroviral medications and seeing a step in the right direction, her health declined and my mother passed away at the age of 46, when I was only 10 years old.

The spark that she ignited, lit up the world. Elizabeth Glaser and so many others sacrificed their lives to provide us the opportunity we have now, to create a world free of HIV, to make sure no one dies from this disease and to make sure no child is ever born HIV positive again.

Through the collaborative efforts of The Pediatric AIDS Foundation, a medication that was designed for a different use was applied to stop in-utero transmission of the virus from mother to child. The Pediatric AIDS Foundation has grown into a community health organization in 19 countries, with over 5,500 sites across the globe and over 30 million women reached to prevent the transmission of HIV to their babies.

Today we are not only an HIV-focused family, our programs support a variety of health issues, most recently being COVID-19.

The ripple that Elizabeth Glaser and Ariel Glaser left in this world will forever be reinforced by each and every one of us who choose to do something when we feel we can’t, who choose to run into our fears when we feel helpless and show each other that even when we feel all hope is lost, in the darkest moments in the darkest places in our lives, light will always prevail if we choose to turn the light on.

Connie Norman (1949-1996)

Story & Recording by Peter Cashman

Constance Robin Norman — Connie — was, contrary to popular belief, born right here in California, in Oxnard in 1949. She had been a boy called Robbie who would later transition to Connie at the age of 26. That was in the mid 1970s.

Hello, I’m Peter Cashman, and Connie was my dear, dear friend.

Many of her formative years were spent in Texas in the Houston area, where her grandmother Mabel Murphy owned a bar. Connie would end up working for Mabel, and there she gained a good deal of the Connie that we came to know. The hard-scrabble life in the South made her streetwise and tough, but with a great sense of humor like Mabel.

Many years later, reflecting on her life, she said, “I often tell people I am an ex-drag queen, ex-hooker, ex IV-drug user, ex-high-risk youth and currently a post-operative transsexual who is HIV positive.” And she added very poignantly, “I have everything I’ve wanted, including a husband of ten years, a home and five adorable longhaired cats…. I do however regret the presence of this virus.”

She had discovered she was HIV-positive in 1987.

Connie had met Bruce Norman in San Francisco. Bruce was a gay man who became her soul mate and husband. He had grown up in the Altadena.

The highlight of Connie’s Bay area years was as a manager at the Trocadero Transfer, the world-famous disco in San Francisco’s Mission District. “Disco Connie” with her huge oriental fans immortalized in the documentary Wrecked for Life.

By the mid ’80s, she and Bruce would attend the weekly “Hay Ride” gatherings in West Hollywood hosted by self-help practitioner Louise Hay. That was where I first remember seeing her and Bruce and many other folks who would join the new national AIDS activist group ACT UP when a chapter formed here in Los Angeles in December 1987.

Connie said she saw ACT UP in the Pride Parade in June of ’88. Straightway she knew that was where she belonged and joined up. She had never attended college; in fact, she’d been a teen runaway on the streets of Hollywood. But she had an insatiable thirst for knowledge. Completely self-taught she put in an enormous amount of work. She would end up co-hosting a weekly cable show in Long Beach. She would write a regular column for the Southern California LGBT newspaper Update. And she would become the very first queer person in the U.S. to host a talk show on AM talk radio, broadcasting from Hollywood.

Connie was fierce and strong, a force to be reckoned with, whether talking with legendary talk radio host Tom Leykis on KFI or with someone she didn’t agree with, like Wally George, appearing on his infamous shock jock talk show on KDOC 56. Speaking at rallies and demonstrations she was loud, forceful and eloquent. By now she was known as the AIDS Diva, to which I added “Self-Appointed and Self Aggrandizing,” typical of the banter between her and I during those times. So she became a statewide figure and was ACT UP/LA’s representative on the LIFE AIDS Lobby.

One thing that really made Connie stand out to me and so many others was her nurturing instinct, her kindness and her ability to speak to people from all walks of life. Connie educated, informed and spoke from the heart, an innate talent that so impressed people. Later she became public policy director at Pasadena’s AIDS Service Center, continuing the work she’d done with ACT UP. Talking with policy makers, lawmakers, locally, in Sacramento and in Washington.

As a respite from the death and dying that surrounded all of us, Connie and Bruce annually took time out with numerous friends, including myself, in their beloved Kauai. A time to tend to rebuilding health and spirit and befriending queer folk all over the island. Her last trip was in late 1995. Her health was failing, and she rapidly declined during the first part of 1996, passing on Bastille Day that year.

Later that year in early October, ACT UP folks gathered from around the country for a second Ashes protest — scattering the ashes of loved ones on the White House lawn. So, my final goodbye to Connie was as I clung to the White House fence, scattering her ashes onto that famous lawn.

Connie Norman – a beloved warrior who remains in our hearts and dreams.

Daniel Warner (1955 – 1993)

Story & Recording by Mark S. King

It wasn’t easy keeping my composure when I interviewed for my first job for an AIDS agency in 1987. Sitting across from me was Daniel P. Warner, the founder of the first AIDS organization in Los Angeles, LA Shanti. Daniel was achingly beautiful. He had brown eyes as big as serving platters and muscles that fought the confines of the safe sex t-shirt he was wearing.

I’m Mark S. King, a longtime HIV survivor.

At 26 years old, with my red hair and freckles that had not yet faded, I wasn’t used to having conversations with the kind of gorgeous man you might spy across a gay bar and wonder plaintively what it might be like to have him as a friend. But Daniel did his best to put me at ease. He hired me as his assistant on the spot, and then spent the next few years teaching me the true meaning of community service.

As time went on, Shanti grew enormously but Daniel’s health faltered. He eventually made the decision to move to San Francisco to retire, but we all knew what that really meant. I was resigned to never see him again.

In 1993, Shanti hosted our biggest, most star-studded fundraiser we had ever produced. It was a tribute to the recently departed entertainer Peter Allen, lost to AIDS, and the magnitude of celebrities who came to perform or pay their respects was like nothing I have ever seen. By that time, I had become our director of public relations, and it was my job to corral the stars into the media room for interviews.

Celebrities like Lily Tomlin, Barry Manilow, Lypsinka, Ann-Margret, Bruce Vilanch, and AIDS icon Michael Callen were making their way through the gauntlet of cameras to the crowded media room. And then one of my volunteers approached me with a look of shock and excitement on his face. He pulled me from the doorway.

“I didn’t know he was going to be here,” he said with wide eyes. “I mean –“

“Who?” I asked. Oh my God. Tom Hanks? Richard Gere?

“He’s with Miss America, Mark,” he said. “They’re right behind me.”

We both turned as the couple rounded the corner of the hallway. They entered the light of the media room and I barely kept a gasp from escaping.

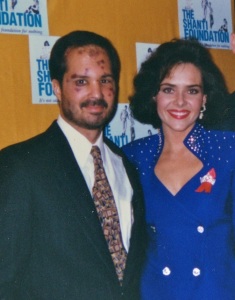

Beautiful Leanza Cornett, who had been crowned Miss America, in part, by being the first winner to have HIV prevention as her platform, had a very small man at her side. His head bore the inflated effects of chemotherapy, which had apparently done little to stem the lesions that were horribly visible across his face, his neck, his hands. His eyes were swollen nearly shut. In defiance of all this, his lips were parted in a pearly, shining smile that matched the one worn by his gorgeous escort.

I stepped into the media room, wanting to collect myself, to wipe the look of pity off my face. I swallowed hard and stepped into the doorway to announce them to the press.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” I said. “Miss America 1993 Leanza Cornett, escorted by Mr. Daniel Warner, co-founder of the Los Angeles Shanti Foundation.”

“Ladies and gentlemen,” I said. “Miss America 1993 Leanza Cornett, escorted by Mr. Daniel Warner, co-founder of the Los Angeles Shanti Foundation.”

The couple walked into the bright light and several flashes went off at once. And then the condition of Miss America’s companion dawned on the camera crews. A few flashes continued, slowly, like a strobe light, and across the room a few of the photographers lifted their eyes from their equipment to be sure their lenses had not deceived them.

Daniel looked to me with a graceful smile, and it became a full, sunny grin as he looked to the beauty queen beside him and put his arm around her. She pulled him closer to her. Their faces sparkled and beamed – glorious, joyful, defiant – in the blazing light of the room.

That man, I thought to myself, that brave, incredible man is the biggest star I have ever seen.

And then the pace of the flashes began to grow as the photographers realized they were witnessing something profound. The couple walked the path through the room and toward the other door.

“Just one more, Mr. Warner?” one suddenly called out.

“Miss America! Just another?”

The room became a cacophony of fluttering lenses and calls to look this way and that, all of it powered by two incandescent smiles.

Daniel and Leanza held tight to each other, their delight lifted another notch as they basked in their final call. Every moment of grace, every example of bravery and resilience I have known from people living with HIV, can be summed up in that glorious instant of joy and empowerment.

“Boss,” I said to him as they exited the room, “I didn’t know you would be here. It’s just… so great.”

He winked at me.

“I’ll be around,” he said. “I brought my whole family with me tonight. I need to get to the party and show off my new girlfriend!”

The three of us laughed, and then I watched Daniel and Miss America, arm in arm, disappear down the hall and into the reception.

Only months later, I received a phone call.

“Mark, this is Daniel,” said a weakened voice. “Monday is my birthday, and I thought that might be a good day to leave.”

Daniel had always been fiercely supportive of the right of the terminally ill to die with dignity and on their own terms. We shared some of our favorite memories of our days at Shanti, and I was able to thank him for his faith in me and setting into motion a lifetime of work devoted to those of us living with HIV.

Daniel P. Warner, as promised, died on his birthday on Monday, June 14, 1993. He was 38 years old.

* * * * *

This story is an edited version of the essay “The Night Miss America Met the Biggest Star in the World,” which Mark S. King published in March 2015 on his website, My Fabulous Disease. Photo credit: Leanza Cornett and Daniel Warner by Karen Ocamb.

My HIV Story

Story and Recording by Mallery Jenna Robinson

Hi! My name is Mallery Jenna Robinson. My pronouns are she/her/hers, I identify as an AfraCaribbean Trans woman who has been empowered in her truth for 16 years as a trans woman and over 10 years as a trans woman living with undetectable HIV.

On May 2, 2011, I was living in Montgomery, Alabama, a junior in college and in a monogamous romantic and sexual relationship with a cisgendered male when I became violently ill and collapsed while working as a server at a local restaurant. I was rushed to the emergency room, where a panel of tests were run including blood work.

I received a phone call from the Montgomery County Health Department on May 21, 2011 to come into the health department to receive an update regarding my recent blood work. The medical provider walked inside the door to the office where I was waiting anxiously, and informed me I was HIV positive. He then referred me to the Copeland Care Clinic, also known as The Montgomery AIDS Outreach, where I would be linked into care at the Ryan White Program to receive HIV care and management.

I was completely nervous and overwhelmed as a then 21-year-old Black trans woman who was working on my Double Bachelor’s in Biology and History, but nonetheless I was determined to not let this diagnosis deter me from living my best life. I arrived at the Copeland Care Clinic and received training on best practices to ensure I would become and remain undetectable. I met my amazing medical provider at the time, Dr. B, and he also recognized that I had no access to hormone replacement therapy, so he also prescribed that along with my anti-retroviral medication.

Despite my medical diagnosis, I was tenacious and determined to continue to live an amazing life and not let HIV define my existence. I was diligent about taking my medication and, as a result, I went from lab work twice a month to lab work once every six months.

I went on to graduate with my double Bachelor’s in biology and history in May 2014. I began teaching as a middle school science and history teacher in Duval County, Florida from August 2014 until June 2019. I traveled to Paris, France and London, England, and finally worked up the gumption to move to Los Angeles, California. After moving to Los Angeles, I began receiving medical care at the Los Angeles LGBT Center under Dr. V.

Since moving to Los Angeles, I have become a transgender and HIV healthcare advocate, raising awareness to promote accessibility, visibility, and equity for all trans identities. I work to destigmatize HIV by professionally speaking about my own journey surrounding HIV as a Black trans woman. I’m a member of the City of West Hollywood’s Transgender Advisory Board, and work as Engagement Specialist and Service Navigator for The Transgender Health Department at the LGBT Center of Long Beach up until 2021. I now work as the Community Advisory Board coordinator for “We Can Stop STDs LA” with Coachman Moore & Associates.

I participate in outreach efforts with other community leaders and partners to ensure that trans women of color and all trans identities in our community are being tested, and getting linked to care and remaining in care. Far too often, individuals hear the letters H-I-V and instantly think of it as a death sentence, but it is not. You can successfully live with HIV as long as you are willing to take your medicines and practice other health and wellness strategies to ensure you are maintaining an undetectable status.

As a Black trans woman who has been living with HIV for over 10 years, I just want to say it is okay to be nervous and overwhelmed. But dig deep and find that determination and tenacity to survive and thrive, so you, too, can motivate and inspire others to stay undetectable by staying in care. Also, if you’re negative, PrEP and PeP services are also available, along with regular HIV testing.

Liberace, 1919-1987

Story and recording by Jake Shears

When I first saw the video from Liberace’s 1978 concert at the Las Vegas Hilton, I was blown away and forever hooked. His mirror-clad, silver Phantom V (Five) Rolls Royce limo is driven onto the stage and, after his chauffeur opens the rear door, Liberace emerges wrapped in a white fox fur coat with a 16-foot train, over a glimmering rhinestone and sequin-studded costume, and rings the size of June bugs. Now that’s an entrance.

I’m Jake Shears, and when I was dreaming up costumes and stage designs for Scissor Sisters, the outrageous, over-the-top looks of Liberace paved the way on a glittery path. His showmanship inspired other performers like Elton John, Lady Gaga and Cher to wow audiences with wild wardrobes, eye-popping glitz, and grandeur. Would Gaga have entered the Grammy’s encased in an egg if decades earlier Liberace hadn’t started his Easter show at Radio City Music Hall by springing from a gigantic Easter egg?

And count me in as number 3. And I actually jumped out of an egg myself at an early Scissor Sisters TV performance many years ago, so eggs all around! I’ll never forget when I went into the Liberace museum in Las Vegas when it was still up and they had the largest rhinestone in the entire world in a glass case, and I’ve never been the same since.

But Liberace was far more than a showman with crazy costumes and gimmicks. He was a very accomplished piano player as comfortable with classical compositions as he was with the popular music of his era. Although critics often scoffed at his playing, he responded, in his words by “laughing all the way to the bank.”

He commanded the stage in Las Vegas for two decades, toured internationally, and starred in his own television variety show, which lasted four years and had 35 million viewers at the height of its popularity. It has been reported that during his hey-day in the 1950s to the 1970s, Liberace was the highest paid entertainer in the entire world. He won two Emmy Awards and six of his albums went gold.

Although he never came out publicly as gay, “his closet had walls of glass,” as the head of his foundation is fond of saying. Anyone who didn’t know this man was gay had willful blindness. Yet he sued a British magazine for libel in 1956 when it clearly implied he was gay. He managed to win that lawsuit and later settled another one with a US magazine that suggested his theme song should be “Mad About the Boy.”

In 1982, Liberace’s 22-year old former bodyguard and chauffeur, Scott Thorson, sued him for support, claiming they had been lovers and lived together for five years. The case settled out of court and Thorson wrote a tell-all book about their life together in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s.

When Liberace died in 1987, his doctor reported the cause of death as a heart attack, but a coroner’s report showed that he died from AIDS-related pneumonia. Two of Liberace’s alleged former lovers also died of AIDS.

Alexis Arquette, 1969-2016

Story & Recording by Patricia, Richmond, David, and Rosanna Arquette

Photo by John Roecker

Patricia Arquette:

We are honored to be asked to memorialize our sister Alexis Arquette. You’ll first be hearing me, Patricia, then our brother Richmond, then David, then our sister Rosanna.

I would like to highlight what an incredible artist Alexis Arquette was. As an award-winning actor, her works spanned the screen, theater and cabaret. As a cabaret singer and M.C. performing at top-level nightclubs, Alexis was a powerhouse, often performing as her self-invented alter ego “Eva Destruction.”

On stage, she starred in Libra with the Steppenwolf Theatre Company for director John Malkovich. Alexis received praise in VH1’s reality show The Surreal Life in 2005, embodying a strong trans role model at a time when transgender representation was literally non-existent.

Her long career in film began with her widely heralded performance as Georgette in Hubert Selby’s Last Exit to Brooklyn. She continued with notable performances in Terminal Bliss, American Playhouse, Hollow Boy, Of Mice and Men, Threesome, Jumpin’ at the Boneyard, Grief, Jack Be Nimble, Pulp Fiction, The Wedding Singer, Bride of Chucky, Killer Drag Queens on Dope, and Wigstock, among many others.

Alexis studied Fine Arts at Otis Parsons. Like her, her paintings are beautiful, evocative, strong, uninhibited, and spirited, encompassing diverse themes such as fantasy, other-worldliness, religious struggle, and erotic art.

Her series of video compilations from local television documented societal norms of the time, capturing blatant anti-LGBT bias. These works also examine human sexuality, desire and desirability through her observing gaze.

When Alexis was dying, she said about her nephew’s work as an artist, “You signed your name on the tree of life.” But I want to say, “Alexis, that you are Darling, you are Brave One, you signed your name on the tree of life, and you will never be forgotten.”

Richmond Arquette:

Alexis was an original, wildly creative, fun and funny, every bit her own person. Her absence continues to be deeply felt. The world is missing out and I wish she were still alive.

Alexis grew up with a president who refused to even mention AIDS by name, let alone take any measures to prevent its spread. She heard the blowhards who judged, criticized and condemned her entire life. I believe the insensitivity in our culture is part of what wore her down.

Death is often reduced to statistics, as if each number isn’t a complete life, intricately interwoven with the lives of those who love them. The recent worldwide effort to address COVID begs the question, why is it not always this way? Why are we not as a species more reverent of life?

I promise you that humanity would be richer if Alexis were still around, and I’m sorry for those of you who never got to be around her.

David Arquette:

Alexis was always ahead of her time. I shared a room growing up with Alexis. He taught me everything I knew about art, Hollywood, fashion, music. She would turn me on to bands years before they became popular.

I’m going to bounce back and forth between pronouns, because that’s what Alexis did.

She was a fighter, always standing up for herself and others. Anyone who knew Alexis loved her. The gangsters, the skaters, the club kids, the runaways. She was a Pied Piper wherever she or he went.

When Alexis decided to live fully as a woman, she also decided to only play female or trans roles as an actress. Again, she was ahead of her time. Despite her career suffering because of that decision, she taught us to stay true to ourselves and fought for us to see a world that we had just not caught up to yet.

Rosanna Arquette:

Alexis passed away before we had today’s language around respectful gender identity. There was no “They/Them” yet.

In this moment of reflection on who our sister was, I’m reminded of just one of the many moments with her where her individuality was crystalized for me. It was a conversation we had in the hours before she left this life. I asked Alexis what clothes she wanted to be dressed in before her cremation. Alexis had every kind of outfit, every type of fluid expression. Fashion was one of the many ways that she shared her creative voice. And Alexis answered, “It doesn’t matter! Me! I’m just me!” We didn’t have the pronouns “They/Them” yet, but that was her message in her final moment with me.

It’s important to recognize and memorialize when any artist breaks new ground. Our sister Alexis Arquette was a pioneer. She was compelling, hypnotic, she drew you in. And she knew she had this power, whether with an individual friend or an endless audience of strangers. She could instantly hold you in the palm of her hand. And when she did, she showed you, me, us, all how to live a life fully self-expressed. She showed us where our own power resides.

Alexis challenged me to be who I am in every moment that I live with fearlessness and pride. In this moment of reflection on who was Alexis Arquette, they were a bad-ass!

Ryan White, 1971-1990

Recording by Jim Parsons

Story by The AIDS Memorial

Ryan White (December 6, 1971 – April 8, 1990) was a teenager from Kokomo, Indiana, who was expelled from his school due to his HIV status. He died when he was 18 years old.

White is buried in Cicero, close to the former home of his mother. In 1991, his grave was vandalized on four occasions.

White, a hemophiliac, contracted HIV through a blood transfusion. He was diagnosed in December 1984 and told that he had only 6 months left to live.

Doctors said that White posed no risk to other pupils. However, when he attempted to return to school, parents and teachers protested against his attendance, scared that he could transmit HIV through casual contact.

The dispute made news headlines around the world and turned White into an advocate for AIDS research and education. Although he lived 5 years longer than predicted, he sadly died just one month before his high school graduation.

Over 1,500 people attended White’s funeral on April 11, 1990 at the Second Presbyterian Church on Meridian Street, Indianapolis. His pallbearers included Sir Elton John AIDS Fundation and Phil Donahue. His funeral was also attended by @MichaelJackson.

Sir @EltonJohn performed a song he wrote in 1969, Skyline Pigeon, at the funeral. White also inspired him to create @ejaf.

On the day of the funeral, former President Ronald Reagan wrote a tribute to White that appeared in The Washington Post. This was seen as an indication of how White had helped change the public’s view of HIV AIDS, especially when considering Reagan’s indifference to the virus. By the time he finally addressed the epidemic in 1987, nearly 23,000 Americans had already perished.

Peter Grant

Story & Recording by Danny Lee Wynter

“Christy Turlington’s legs are the bees knees” he said flicking through my mum’s copy of Vogue. I’d never seen anyone like him. Exquisitely dressed, Peter Grant, my mother’s childhood friend arrived in my life when I was 8. A time I was terrified of being me. I was aware of him throughout my childhood. I didn’t really know him but I knew how he made me feel. Awkward. Embarrassed. Brimful with self loathing. Peter was what kids today describe as a ‘femme queen.’ And every inch of him denoted his right to be so.

I heard little about Peter in the intervening years. Then one day I overheard my mum saying he had AIDS. The news paralysed me. At 11, it was something nobody in my surroundings was sympathetic to. I learnt of Peter’s death while in the midst of experiencing the routine humiliations of a young homosexual in high school. The skirting about the issue of why you don’t have a girlfriend. The shame of the changing rooms during games practice and feigning asthma attacks to be excused. When Peter died I was still denying the biggest part of me which only came to life in the art rooms or choir practice.

Peter’s funeral took place where he died, the London Lighthouse. I was asked to sing at the service. Hesitant at first, I made the connection as to why I’d been so scared of him. I felt I owed him an apology, so I sang Barbra Streisand’s ‘The Way We Were’ accompanied by the piano. There surrounded by his lover, family, friends and the staff who cared for him, I encountered for the first time a tribe unlike any I’d ever come into contact. I was 13. At one point my mum points to a severely handsome man sat holding his boyfriend’s hand. He was as ‘masculine’ as any man I grew up with. ‘That’s Guy!’ my mother’s friend whispered, ‘I wish he was my Guy!’ mum replied, my tiny frightened childish mind blown.

Years later I would come to experience the gay community’s own deep and complex relationship with the performance of masculinity and the chastising of those deemed ‘too femme’ or too much like Peter! I think back to the scared little boy who met him and now know you can’t ever be too much of yourself. Peter taught me that.

Joan Baker, 1966-1993

Story & Recording by Judith Cohen

My friend, Joan Baker was diagnosed with AIDS in 1986 and died on September 3, 1993. She was a tireless and outspoken activist who unfortunately had to deal with ignorance and misunderstanding from her own (lesbian) community … ergo, she would often say:

“It doesn’t matter how I got it, it’s that I have been diagnosed and I am coming out as a women with AIDS because a lot of lesbians still think that they cannot get AIDS and I’m here to say that this can and did happen.”

In early October 1993, members of San Francisco Lesbian Avengers and ACT UP held a public funeral demonstration and march that went from from Dolores Park to Market and Castro and was covered on television news that night. This would end up being likely the only public funeral for a lesbian with AIDS anywhere, ever.

The images of the demo/funeral posters of Joan which were carried that day are now held at the GLBT History Museum in San Francisco.

We love you and we miss you incredibly, Joan. Thank you for your inspiration, your contribution, your life and love.

Pedro Zamora, 1972-1994

Recording by Wilson Cruz

Story by The AIDS Memorial and Irwin M. Rappaport

Photo © MTV

Pedro Zamora’s bravery and commitment to AIDS advocacy engaged and educated TV audiences around the world. Pedro was a cast member on Real World: San Francisco from 1993 to 1994. I’m Wilson Cruz, and hardly a day goes by that I don’t remember Pedro’s courage and dedication.

On Real World: San Francisco, Pedro was one of the first openly gay people with AIDS that many people ever saw on TV. Simultaneously, on My So Called Life, I was the first openly gay actor playing an openly gay character in a series regular role on American TV. And to this day, Pedro still inspires me as an actor, as a man, and as an activist.

Pedro Zamora was the youngest of eight children living in Havana, Cuba when his parents decided to emigrate to Florida as part of the highly-publicized Mariel Boat Lift in 1980. Pedro was an honor student, captain of the cross-country team and President of the Science Club at his high school where he was voted Best All Around and Most Intellectual. But at 17 years old, Pedro learned he was HIV positive after donating blood at a blood drive.

His HIV-positive diagnosis propelled him to become a full-time AIDS educator, so that other young people could learn what he was never taught. This led to hundreds of speaking engagements; a front page article about him in the Wall Street Journal; appearances on major talk shows hosted by Oprah Winfrey, Geraldo Rivera and Phil Donahue; and testimony before the U.S. Congress on AIDS education.

Producers of the Real World wanted to cast an HIV-positive person. Being cast on the series gave Pedro his biggest platform for AIDS education and won him fans all over the world. Audiences watched how his HIV status affected his relationships with housemates and his health. They celebrated his commitment ceremony with partner Sean Sasser, which was the first such ceremony in the history of television.

But about midway through the taping of the series, Pedro’s health began to decline, but he told producers that he wanted them to tell his story until the end. When the stress from his conflict with a homophobic housemate, Puck Rainey, led Pedro to want to move out of the Real World house, his other housemates instead voted to evict Rainey. Time magazine ranked that episode #7 of the top 32 most epic episodes in reality TV history.

In late June 1994, the Real World: San Francisco began to air on MTV. At a cast reunion party only two months later in August, Pedro’s progressing illness was evident. He was diagnosed with toxoplasmosis, a disease that causes brain lesions, and also a rare and often fatal virus that causes inflammation of the brain. Doctors estimated that he had 3-4 months to live.

In September 1994, he was transferred to a hospital in Miami near his family. With the help of the U.S. government, the remainder of his family was allowed to move to the U.S., so that they could be with Pedro before he died. MTV paid for his medical costs, because Pedro was unable to get health insurance due to having a pre-existing condition.

Pedro Zamora died of AIDS at age 22, the morning after the final episode of the show was broadcast.

A memorial fund, youth clinic, a public policy fellowship, a youth scholarship fund and a street in Miami are named in Pedro’s honor. He was one of the 50 people first included on the National LGBTQ Wall of Honor as part of the Stonewall National Monument, the first national monument in the U.S. dedicated to LGBTQ history.

Reflecting on Pedro’s death, President Clinton reminded us, “We must remember what Pedro taught us: One person can change the world — and whether or not we are living with HIV or know someone who is, we all have a responsibility as global citizens to do whatever we can. Life is short enough as it is. No one should die from a disease that is both preventable and treatable.”

Tim Richmond (1955-1989)

Recorded by Karleigh Webb

Story by The AIDS Memorial, Irwin Rappaport and Karleigh Webb

A version of this story first appeared on The AIDS Memorial on Instagram

Photo from Tim Richmond: To the Limit (ESPN)

NASCAR’s rough-and-tumble history has its share of legends and folk heroes down South. But a Northerner named Tim Richmond may be the wildest of the bunch.

Hello everybody, I’m Karleigh Webb. I’m a sports journalist with outsports.com, a transwoman athlete, an activist, and I’m a lifelong motorsports fan. As youngster watching NASCAR in the 1980s, I was a fan of Tim Richmond. Because he was that dude. High energy. Free spirit. Raw Talent.

NASCAR commentator Mike Joy recalled, “When he walked into a room, there was suddenly a party going on. And it was just that infectious enthusiasm for life and for racing that really defined him … He was fun to be around. He knew he was the center of attention, and he really kind of cherished it.”

Perhaps that’s why Richmond had the nickname “Hollywood,” and inspired Tom Cruise’s character in the movie Days of Thunder. He was fun even when he was trying to be serious. When team owner Rick Hendrick told Tim to clean up his appearance, the driver responded by appearing in a silk suit, clutching a purse, and a cane like an old woman.

The Tim Richmond story began in his native Ohio, with dreams of Indianapolis. In 1977, he was Rookie of the Year at Sandusky Speedway and was a track champion. In 1978, he was the U.S. Auto Club’s national sprint car Rookie of the Year. In 1980, he was Indianapolis 500 Rookie of the Year. But after that, Richmond took an offer to head south to NASCAR.

He snagged his first of 13 career wins in 1982 on the road course at Riverside. By the end of the 1984 season, Esquire magazine tagged him one of the “best of a new generation.” 1986 was the breakthrough year. Driving for owner Rick Hendrick, Richmond became a Winston Cup championship threat — seven wins, third in the championship. And the Motorsports Press Association named both Tim Richmond and ‘86 Winston Cup Champion Dale Earnhardt as Co-Drivers of the Year.

In 1987, an illness reported as double pneumonia caused him to miss the first 11 races. But when Tim Richmond came back, boy, he came back. He won at Pocono, and then followed it up back-to-back with a win at Riverside. But after six more starts that year, he was too ill to keep driving.

He tried another comeback in 1988. NASCAR reported that he tested positive for banned substances and was suspended prior to start of qualifying for the Daytona 500 that year. Richmond denied the findings and challenged them publicly.

Days later, those substances were identified as Sudafed and Advil. Richmond sued NASCAR for defamation and later settled out of court. He was retested and reinstated later in the year but couldn’t find a ride for any team. By then the rumors concerning Richmond, HIV and AIDS were prevalent. He denied those rumors as well. A doctor friend claimed that Tim was hospitalized due to a motorcycle accident.

Tim Richmond died on August 13, 1989, at the age of 34.

Ten days after his death, his family announced at a press conference that he had died from complications from AIDS and was diagnosed during his breakthrough season in ‘86. It was asserted that he had become infected through sex with an unknown woman. A few months following his death, a Washington DC television station reported on sealed court documents and interviews that showed that a doctor employed by NASCAR had falsified drug test results to keep Richmond out.

Looking back at a brief yet brilliant career, Rick Hendrick concluded that Tim Richmond was 20 years ahead of his time.

“I think he was good for the sport,” Hendrick observed. “He had a tremendous following of fans. He could drive anything. Not afraid of anything. We need a little bit of that charisma today.”

During NASCAR’s 50th anniversary celebrations in 1998, Tim Richmond was named one of the top 50 drivers of all time. In 2002, he was inducted into the International Motorsports Hall of Fame.

Leonard Matlovich (1943-1988)

Recorded by Lt. Gen. Leah Lauderback

Story by The AIDS Memorial and Irwin M. Rappaport

A version of this story first appeared on The AIDS Memorial on Instagram

Photo by Ted Thai, Time magazine

Leonard Matlovich was a decorated Vietnam War veteran who came out as gay to challenge the U.S. military’s ban on gays and lesbians.

Following in the footsteps of his Air Force veteran father, Matlovich voluntarily enlisted in the Air Force in 1963 at the age of 19 and served three tours of duty. He received a Bronze Star for heroism under fire, and a Purple Heart after he was seriously wounded by a land mine.

I’m Air Force Lieutenant General Leah Lauderback. Openly LGBTQ servicemembers like me owe a debt of gratitude to the courage of Leonard Matlovich and I’m deeply honored to tell his story.

After serving in Vietnam, Sgt. Matlovich was posted at an air base near Pensacola. There, he started visiting gay bars and, at the age of 30, had his first relationship with a man but stayed in the closet in the military for over another year.

The Air Force assigned Matlovich to teach race relations, and he traveled the country to coach other instructors. That experience helped him to understand the similarities between discrimination on the basis of race, and discrimination against the gay and lesbian community.

After reading an article by gay rights activist Frank Kameny in the newspaper The Air Force Times, he contacted Kameny and they devised a plan with the ACLU to challenge the ban on gays and lesbians in the military. On March 6, 1975, he hand-delivered a letter to his commanding officer announcing that he was gay. His brave pronouncement landed him on the cover of Time magazine in September of

1975.

When he refused to promise never again to engage in homosexual conduct, he was

discharged from the Air Force in October of that year. He sued for reinstatement and, after a long court battle, a federal judge ordered the Air Force to reinstate and promote him. Rather than risk discharge for a made-up reason or an appeal of the court decision by the military, Matlovich accepted a financial settlement and dropped the case.

Leonard’s activism continued with his fundraising and advocacy efforts against Anita Bryant’s campaign to overturn a non-discrimination ordinance in Florida and against an attempt to ban gays and lesbians from teaching in California.

He moved to Guerneville, California on the Russian River, where he opened up a pizza restaurant. Later he moved to San Francisco and worked as a car salesman. In 1986, after fatigue and a prolonged chest cold, he tested positive for HIV. In 1987, Leonard came out as HIV positive on “Good Morning America.” He continued his advocacy and later that year he was arrested in front of the White House protesting the Reagan Administration’s inattention to HIV and AIDS.

Leonard Matlovich died on June 22, 1988. He chose to be buried in Congressional Cemetery in Washington D.C. where, unlike Arlington National Cemetery, he could have a tombstone which omits his name. His tombstone simply reads: “When I was in the military, they gave me a medal for killing two men and a discharge for loving one.”

As a final joke, Leonard chose a grave site in the same row as J. Edgar Hoover, the infamous FBI Director who is widely believed to have been a closeted gay man.

Matlovich was one of the 50 people first selected for inclusion in the National LGBTQ Wall of Honor at the Stonewall National Monument in New York City. Leonard’s courage paved the way for service members like me to openly serve.

Thank you, Leonard “Mat” Matlovich, for your tenaciousness and your leadership. And lastly, I thank you for your service to this nation.

Rand Schrader (1945 – 1993)

Recording by David Bohnett

Story by Karen Eyres and David Bohnett

Rand Schrader was an openly gay activist who fought discrimination and homophobia to become one of the first two openly gay California municipal court judges appointed in 1980 by then-Governor Jerry Brown. This was a time when the majority of voters in the state supported conservative Ronald Reagan for president.

I’m David Bohnett, and I was Rand’s partner for 10 years.

As a UCLA Law School student in the early 1970s, Schrader volunteered countless hours providing legal guidance to leaders at the Los Angeles LGBT Center (then called the LA Gay Community Services Center). Many of his cases involved police discrimination against gay men.

After graduating from UCLA in 1973, Schrader took a job with the City of Los Angeles, becoming the first openly gay staffer in the city attorney’s office. Then-City Attorney Burt Pines was impressed with Schrader’s work, saying the young staffer was able to command respect from people across the political spectrum. In 1980, Governor Jerry Brown appointed Schrader to the LA Municipal Court and immediately received pushback from conservative politicians expressing public outrage at the judicial appointment of an openly gay man. Brown held firm on his decision.

In 1987, Los Angeles County established an AIDS Commission, and Schrader was among its first cohort of commissioners. At the time, LA county had surpassed San Francisco in the number of HIV and AIDS cases. San Francisco had established an AIDS ward at San Francisco General Hospital in 1983, but there was nothing comparable in LA County.

The Los Angeles chapter of ACT UP organized a steady stream of demonstrations at LA County Medical Center, demanding that persons living with HIV and AIDS be provided with a specialized unit that would protect them from discrimination and neglect. As a commissioner, Schrader found himself siding with the activists and at odds with the AIDS Commission’s chairman, Rabbi Allen Freehling, who argued that patients put in a separate unit would feel isolated. The commission formed a task force to determine a course of action, and soon it became apparent that people living with AIDS would benefit significantly from access to having their own clinic.

In 1988, the LA County Hospital finally opened a ward dedicated to AIDS healthcare. The next year, Schrader was elected the new chair of the AIDS Commission.

When Schrader was diagnosed with AIDS-related illness in 1991, he went public with his condition and continued his work in the municipal court and on the AIDS Commission. Two years later, the LA County Board of Supervisors unanimously approved a motion to name the LA County AIDS ward after Schrader in tribute to his courage, his vision and his tenacity.

Rand Schrader died of AIDS-related illness on June 13, 1993 at the age of 48.

As I said in 1999, “When Randy died, I honestly did not know how I could go on. But I had friends. I had a family — mine and Randy’s. And we all shared our grief and comforted one another during our time of loss. But what if I had been alone in that grief? What becomes of a man or woman when one loses a partner whom no one else knows was a partner? What happens to people who are afraid to tell the truth about who they are and whom they love?”

While I grieved Randy’s passing and with these thoughts in mind, I created the very early social network e-commerce company GeoCities.com, where people could create free personal web pages on the internet; give voice to their hopes, dreams and passion; and find connection with one another.

Randy’s legacy also endures in the HIV/AIDS clinic he helped to create. Today, the University of Southern California manages the Rand Schrader HIV Clinic, where more than 40 faculty members provide primary and specialty care to more than 3,000 patients in LA County.

Rest in peace, my dear Randy.

No on 64

Story & Recording by Torie Osborn

I’m Torie Osborn, telling the story of the “No on 64” campaign against the heinous 1986 proposition to quarantine people with AIDS, put on the California ballot by right-winger Lyndon LaRouche.

Remember, that was during the dark time when AIDS was still new, all the urban gay and bi-men were at risk, there was zero treatment, and the general population still thought it was transmitted in the air, if not by mosquitos. Early polling showed a potential big win for Prop 64 – largely due to the fear and misinformation out there. Seventy percent of the electorate was undecided. But our community rallied, and in four short months, we won the day.

Our campaign consultant was David Mixner – the best in the biz in our world. He’d headed up the “No on 6” campaign in 1978 against the Briggs Initiative to fire gay teachers. I was Southern California Campaign Coordinator for “No on 64,” and Dick Pabich (R.I.P) was my counterpart up north. Co-chairs of the campaign were Harry Britt and Diane Abbitt. So many who are now gone were key spokespeople, such as Rob Eichberg, Randy Klose, Duke Comegys, Bruce Decker, Peter Scott, Jean O’Leary.

We’d learned from Prop 6 that to win, we needed both the volunteer-driven, grassroots mobilization arm and the paid professional campaign, so “Stop LaRouche” worked alongside “No on 64” campaign — we were tightly coordinated. It was run by Ivy Bottini, Lee Werbel, Phill Wilson, and others.

AIDS phobia was so widespread that at the start of the campaign, no mainstream liberal groups – except the docs and nurses — were with us, except the Southern California ACLU chapter, and a few random Hollywood straight types, like Paul Newman. But we mobilized like crazy.

In four short months, we raised over $2 million, 90% of which came from our own community, and mounted a professional, bi-partisan campaign that ended up winning 71% of the vote in November.

We had hundreds of House Parties and a thousand volunteers who spoke at every civic club and community group and Dem Club around the state. By the last month, every single slate card, every labor union, everyone was with us. And every voter in California – including every Republican! – received a strong “NO on 64” mailer.

That 71% victory belonged to our entire LGBTQ+ community that rose up en masse to forge a victory out of the agony of AIDS, and, in the course of it, firmly established ourselves, alongside medical experts, as trusted spokespeople on the issue of HIV and AIDS.

Rev. Dr. Stephen Pieters: Survivor & Trailblazer

(1952-2023)

Recording (2022) by Jessica Chastain

Story by Irwin M. Rappaport

The Rev. Dr. A. Stephen Pieters is an AIDS survivor, an AIDS activist and a pastor who ministered to people with AIDS from the earliest years of the AIDS epidemic. Steve received his Master of Divinity Degree from McCormick Theological Seminary in 1979 and became pastor of the Metropolitan Community Church in Hartford, Connecticut.

In 1982, Steve resigned his position as pastor in Hartford and moved to Los Angeles. A series of severe illnesses in 1982 and 1983 eventually led to a diagnosis in 1984 of AIDS, Kaposi’s Sarcoma and stage four lymphoma. One doctor predicted he would not survive to see 1985.

And yet, 1985 proved to be a watershed year for Rev. Pieters. He became “patient number 1” on suramin, the first anti-viral drug trial for HIV which led to a complete remission of his lymphoma and Kaposi’s sarcoma. Unfortunately, suramin was found to be extremely toxic, and it came close to killing him twice.

Also in 1985, during his suramin treatments, he appeared via satellite as a guest on Tammy Faye Bakker’s talk show, Tammy’s House Party, on the Bakkers’ PTL Christian network. Tammy Faye took a huge risk with her evangelical Christian audience by inviting Pieters on the program and advocating for compassion and love for gay people and people with AIDS.

I’m Jessica Chastain, and portraying Tammy Faye in her interview with Rev. Steve Pieters was one of the highlights of my role in the 2021 film The Eyes of Tammy Faye. The interview was done via satellite because of fears that the PTL crew would not be comfortable with an in-person interview.

Steve told People magazine that: “She wanted to be the first televangelist to interview a gay man with AIDS. It was a very scary time and there was still a lot of fear about AIDS and about being around a person with AIDS. And I thought the opportunity to reach an audience that I would never otherwise reach was too valuable to pass by. I’ve had people come up to me in restaurants and tell me, ‘That interview saved my life. My mother always had PTL on, and I was 12 when I heard your interview, and I suddenly knew that I could be gay and Christian, and I didn’t have to kill myself.'”

Tammy Faye’s support for people with AIDS and the gay and lesbian community continued. Bringing

along her two children, she visited AIDS hospices and hospitals, went to LGBT-friendly churches, and

participated in gay pride parades.

When the Bakkers’ PTL network and Christian amusement park were embroiled in scandal and she became the subject of jokes and Saturday Night Live skits, she said in her last interview, “When we lost everything, it was the gay people that came to my rescue, and I will always love them for that.”

Tammy Faye passed away from cancer in 2007, but Rev. Pieters continues to thrive both personally and professionally. He has served on numerous boards, councils, and task forces related to AIDS and

ministering to those with AIDS, and his series of articles about living with AIDS was collected into the

book I’m Still Dancing. For many years, Pieters served as a chaplain at the Chris Brownlie Hospice,

where he discovered a gift for helping people heal into their deaths.

Pieters was one of twelve invited guests at the first AIDS Prayer Breakfast at the White House with U.S. President Bill Clinton, Vice President Al Gore, and the National AIDS Policy Coordinator in connection with World AIDS Day 1993, and President Clinton spoke about Rev. Pieters in his World AIDS Day speech on December 1, 1993.

Pieters has been a featured speaker for AIDS Project Los Angeles and his story is told in the

books Surviving AIDS by Michael Callen, Voices That Care by Neal Hitchens, and Don’t Be Afraid Anymore by Rev. Troy D. Perry. He has received many awards for his ministry in the AIDS crisis from

church organizations, the Stonewall Democratic Club in Los Angeles, and the West Hollywood City

Council.

In 2019, his work in AIDS Ministry, including his Tammy Faye Bakker interview, became part of the LGBT collection in the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. Pieters left his position with UFMCC AIDS Ministry in 1997, earned a masters’ degree in clinical psychology, and worked as a psychotherapist at Alternatives, an LGBT drug and alcohol treatment center in Glendale, California.

Now retired, Pieters is busier than ever with speaking engagements, interviews, and finishing up his memoir. He has been a proud, singing member of the Gay Men’s Chorus of Los Angeles since 1994.

* * * * *

Steve Pieters passed away on July 8, 2023, at age 70. Pieters’ memoir, Love is Greater than AIDS: A Memoir of Survival, Healing, and Hope, was published posthumously in April 2024.

Marlon Riggs (1957-1994)

Recording by Lee Daniels

Story by Irwin M. Rappaport

Photo: Marlon Riggs in foreground, shown with Essex Hemphill in 1989

Filmmaker and professor Marlon Riggs proclaimed that “Black men loving Black men is THE revolutionary act.”

Born in 1957, Marlon Riggs graduated magna cum laude from Harvard in 1978. In 1981, at Cal Berkeley, he received a master’s degree in journalism, with a focus on documentary film. He later became the youngest tenured professor at Berkeley’s Graduate School of Journalism and won a string of prestigious awards in his tragically short career.

Hi, I’m Lee Daniels, two-time Oscar-nominated director and producer of Precious and The Butler, and co-creator of the television series Empire.

In its introduction to its collection of seven of Riggs’ films, the Criterion Collection describes Riggs as “an unapologetic gay Black man who defied a culture of silence and shame to speak his truth with resounding joy and conviction. An early adopter of video technology, Riggs employed a bold mix of documentary, performance, poetry, and music in order to confront the devastating legacy of racist stereotypes, the impact of AIDS on his community, and the very definition of what it means to be Black.”

Amidst the culture wars of the 1990s, Marlon exposed and explored what it’s like to be intersectional, to be gay, Black and marginalized in a culture with defined expectations for Black masculinity. In the film Tongues Untied, Marlon came out as gay and HIV positive but also was clear in his objective of making a film about and for Black gay men.

The principal virtue of the film, in his words, was “its refusal to present an historically disparaged community on bended knee, begging courteously for tidbits of mainstream tolerance.” The International Documentary Association describes the film as “a manifesto that calls for Black gay men to unburden themselves of the shame-induced silence and claim the centrality and dignity of their identity and voice.”

Former Reagan Communications Director Pat Buchanan, running for President in 1992, used clips of the film to attack President George H.W. Bush as too liberal because tax dollars were being used to support what Buchanan called pornography and immorality. Riggs had received a grant of only $5,000 for Tongues Untied from the National Endowment for the Arts. PBS released the film as part of its POV series. Although some public TV stations wouldn’t broadcast it, Tongues Untied was the first televised documentary about the Black gay experience. Riggs was diagnosed with HIV during the filming of that documentary.

Riggs didn’t shy away from the controversy. As he put it, “My struggle has allowed me to transcend that sense of shame and stigma identified with my being a Black gay man. Having come through the fire, they can’t touch me.”

Riggs won an Emmy in 1988 for Ethnic Notions, a documentary about Black stereotypes that fueled racial prejudice. He received the prestigious Peabody Award in 1992 and the Distinguished Documentary Achievement Award in 1991 from the International Documentary Association for his documentary Color Adjustment, which tracked 40 years of the denigrating and exploitative depiction of Black Americans in primetime television. Tongues Untied won the Los Angeles Film Critics Award and won Best Documentary at the 1988 Berlinale Film Festival.

Riggs died of complications due to AIDS in 1994, at the young age of 37. His film Black Is, Black Ain’t was completed after his death. It won the Grand Jury Prize and Filmmakers Trophy at the 1995 Sundance Film Festival. In 2022, Tongues Untied was added to the National Film Registry at the Library of Congress.

Marlon Riggs is the reason that I am here today.

Michael Jeter, 1952-2003

Recording by Annette Bening

Story by Irwin Rappaport and Annette Bening

Photo from “Evening Shade” (CBS)

Kids and kids at heart knew Michael Jeter as “The Other Mr. Noodle” on Sesame Street. Others would recognize him as Eduard Delacroix, the death row prisoner with pet mice from the film The Green Mile, or as the hilarious homeless man with AIDS who became a balloon-bearing birthday singer in drag in The Fisher King.

Standing at 5 feet 4 inches, Michael was the unlikely and excitable assistant football coach to Burt Reynolds on the series Evening Shade. He won an Emmy Award for that role, and a Tony Award for his performance in the Broadway musical Grand Hotel.

I’m Annette Bening. Kevin Costner and I had the privilege of working with Michael on the film Open Range. He was an absolute delight, a hard worker, a jokester and he had a heart of gold.

Other notable credits for Michael included a sweet mental hospital patient in Patch Adams, a mercenary hunting dinosaurs in Jurassic Park III and Emmy-nominated guest starring roles on the television series Picket Fences and Chicago Hope.

Michael was candid about his battles with drug and alcohol addiction, which led him to quit acting for a while, until he was brought back to TV with a small role in Designing Women. In his Tony Award acceptance speech, he offered himself as living proof that people with an addiction can stop, can change their lives one day at a time, and that their dreams can come true.

Michael was also open about his homosexuality and HIV-positive status, disclosing it in an interview with Entertainment Tonight in 1997, where he said “you’re as sick as your secrets.” He counseled young people about protecting themselves from contracting HIV.

In Grand Hotel, Michael portrayed Otto, a mortally-ill small-town bookkeeper who wants one night living the good life in the big city before he dies. Reviewing the show for The New York Times, Frank Rich wrote, ”Mr. Jeter lets loose like a human top gyrating out of control — literally breaking out of his past into a new existence.”

Michael Jeter died unexpectedly of an epileptic seizure in 2003, leaving behind his partner of many years, Sean Blue. Our film Open Range and his last film, The Polar Express, were both dedicated to Michael. As Robin Williams observed when Michael died, “He lit the place up.”

Tom Waddell (1937-1987)

Story and Recording by Jessica Waddell-Lewinstein Kopp

Once described as “the world’s most eclectic person,” Dr. Tom Waddell was a great man, most notable for his participation in the 1968 Olympics and the founding of The Gay Games.

It was while working on the Gay Games that Dr. Tom Waddell met Sara Lewinstein, a prominent and local Bay Area gay and women’s rights activist who came from a strong family of WWII survivors. After becoming best friends, they decided to do what much of society considered unheard of at the time and welcome a child into an openly LGBTQ family.

Hello, I am Jessica Waddell-Lewinstein Kopp, and I am the daughter of Dr. Tom Waddell and Sara Lewinstein.

My dad attended college on a football scholarship. After graduating, he pursued his medical degree and joined the Army as a preventative-medical officer and paratrooper, before going on to work as a doctor who specialized in infectious disease. In 1968, he joined Team USA for the Olympics in Mexico City where he secured 6th place in the Decathlon, followed by goodwill track and field tours across South America and Africa with his fellow teammates. He sadly injured himself before he could participate in the 1972 event but went on to work as a physician for the Saudi Royal Family in in Riyadh as well as the Saudi Arabian Olympic team at the 1976 Olympics in Montreal.

In the late 1970s, he decided to become one of the first professional athletes to publicly come out as a gay man with his partner, Charles Deaton, a former CIA operative. It was also around this time that he finally started to settle down in San Francisco, California – a place where he had always found he was fully able to embrace the beautiful, diverse and flourishing open-minded culture of the Bay Area.

After spending many years travelling the globe, he had a vision. Inspired by the founding principles of the Olympics, he wanted to build an international sporting event that sought to triumph over the discrimination and marginalization he had witnessed all over the world and provide a space for open expression, celebration of identity, and athletic competition. He envisioned the Gay Olympics.

Aware that sports didn’t always offer a welcoming environment for many gay people, the Gay Olympics would be an event that would allow all people, regardless of sexuality or other forms of identity, to come together at all skill levels, have fun, and compete. But when the Gay Olympics were ready to launch in 1982, the U.S. Olympic Committee, having been awarded exclusive use of the word “Olympic,” sued for trademark infringement and won. To say my dad was disgusted was an understatement. This was a move blatantly motivated by discrimination against gay men and lesbians.

Overcoming his anger, he rebranded the event as the Gay Games, revised the promotional and marketing materials, and launched the event that summer with over 1,300 athletes from 170 worldwide cities and 12 countries.

In January 1985, when I was about a year-and-a-half, my dad noticed some white patches on his tongue while brushing his teeth, quickly recognizing it as a possible sign of the HIV/AIDS virus that was emerging as a threat in the community. Testing confirmed that he was right. Still, he continued to focus on planning the next quadrennial event, which was to be held again in San Francisco in the summer of 1986.

As the date for Gay Games II approached, my dad’s health was in decline. I remember visiting him in the hospital at one point. And even though he was bed-ridden, he still managed to pick me up two little figurines from the gift shop (that I still have) to show me he was thinking of me.

But that was not the end! He was so committed to the Gay Games that in a last feat of strength, he checked himself out of the hospital to march into the Opening Ceremonies, deliver an opening address, and take home a gold medal in the javelin event. The second event drew 3,500 athletes from 251 cities and 17 countries.

Within a year of the event, my dad was gone. After the Games, his health had continued to decline, and in July 1987, he uttered his last words of “Well, this should be interesting” at our home in San Francisco with my mom.

He was 49, and I was three. My own understanding of what was happening was limited, and I firmly believed that like Sleeping Beauty, if I could just find my dad and give him a kiss, he would wake up and be with me again. And although I would soon realize I wouldn’t be getting him back, I did later learn that he left an incredible legacy that would stay with me throughout my life.

The Gay Games lives on today and are held every four years in new locations. For over 40 years, the Federation of the Games has continued to propel acceptance of diversity and advocate for a world where dignity and inclusion are the cornerstones of society.

When people talk about great people and who their heroes are, he is mine. I could not be prouder of the man my father was, and what he accomplished in his lifetime, alongside the positive impact he had on this world.

Charles Ludlam (1943-1987)

Recorded by Jackie Beat

Story by Karen Eyres

Photo courtesy of the New York Public Library, Billy Rose Theater Collection

Charles Ludlam was the king — and sometimes queen — of downtown theater. As founder of the Ridiculous Theatrical Company in New York City, Ludlam was an actor, drag artist, writer and director – and one of the most prolific artists on the off-Broadway scene in the 1970s and ’80s.

I’m Jackie Beat, and I want to say right here and right now that drag artists and writers such as myself would not exist were it not for Charles Ludlam.

For nearly 20 years, Ludlam drew dedicated fans to a small basement theater in Greenwich Village for parodies that included Bluebeard, Reverse Psychology, and the Maria Callas spoof Galas. Although Ludlam’s plays were characterized by cross-dressing, free use of double-entendre and comic exaggeration, he resisted attempts to categorize his work as camp. He explained it this way:

”If people take the time to come here more than once, they see I don’t have an ax to grind – even though I do have a mission. That mission is to have a theater that can offer possibilities that aren’t being explored elsewhere.”

The Ridiculous Theatrical Company toured extensively in the U.S. and Europe, and Ludlam received a Drama Desk award and six Village Voice Obie awards. He made forays beyond his own company, as well.

In 1984, he played the title role in the American Ibsen Theater production of Hedda Gabler; and in 1985, he staged the American premiere of The English Cat by Hans Werner Henze for the Santa Fe Opera. Ludlam received fellowships from the Guggenheim, Ford and Rockefeller foundations and a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts.

In early 1987, Ludlam was retained by producer Joseph Papp to direct the production of William Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus for the New York Shakespeare Festival in Central Park. But in March of that year, Ludlam was diagnosed with AIDS and, a month later, he was admitted to St. Vincent’s Hospital.

Ludlam called Papp from his hospital bed to say he couldn’t direct Titus for him. Papp promised to reserve the play for him, perhaps for next season, in a space at the Public Theater. Ludlam’s condition quickly worsened, and he died on May 28, 1987. He was 44 years old.

His obituary appeared on the front page of The New York Times, the first obituary that directly named AIDS as the cause of death. His sixth Obie award, the Sustained Excellence Award, was presented two weeks before his death.

In 2009, Ludlam was posthumously inducted into the American Theater Hall of Fame. The street in front of his theater in Sheridan Square was renamed Charles Ludlam Lane.

Rev. Bernárd Lynch: A Priest on Trial

Story & Recording by Cosgrove Norstadt

Photo © Life Through a Lens Photography

With so many tributes to loved ones who fell victim to HIV and AIDS, I want to pay tribute to one man who has devoted his life to caring for those with HIV and AIDS. This one person has made such a positive impact on the LGBTQIA community and has literally ministered to thousands of men who were alone and lost. This man is Reverend Bernárd Lynch.

During the AIDS crisis of the 1980s and ‘90s, Bernárd was a tireless voice in the New York City community and traversed the difficult road of illness and death. His leadership served as a beacon of light to those of us lost in the sea of dying faces we could not save. Bernárd took up a fight of which many other men shied away. This man used every ounce of his being to provide care to those who died and to those of us living and blindsided by AIDS. Bernárd’s faith in God never wavered.

Bernárd is an out and proud Roman Catholic priest who has marched in the Gay Pride parades of New York and London for the past 30 years. He has touched the hearts of gay men and lesbian women from the shores of the United States to England to his homeland of Ireland. Few men living can be called icons, but I certainly would call Bernárd an icon.

Bernárd’s list of accomplishments is long and varied. He has worked for the betterment of the LGBT community worldwide.

Father Lynch first came to notice in New York City in 1982 when he formed the first AIDS ministry in New York City with the Catholic group Dignity. It was this same year that he was drafted to work with the then-New York City Mayor Koch’s Task Force on AIDS.