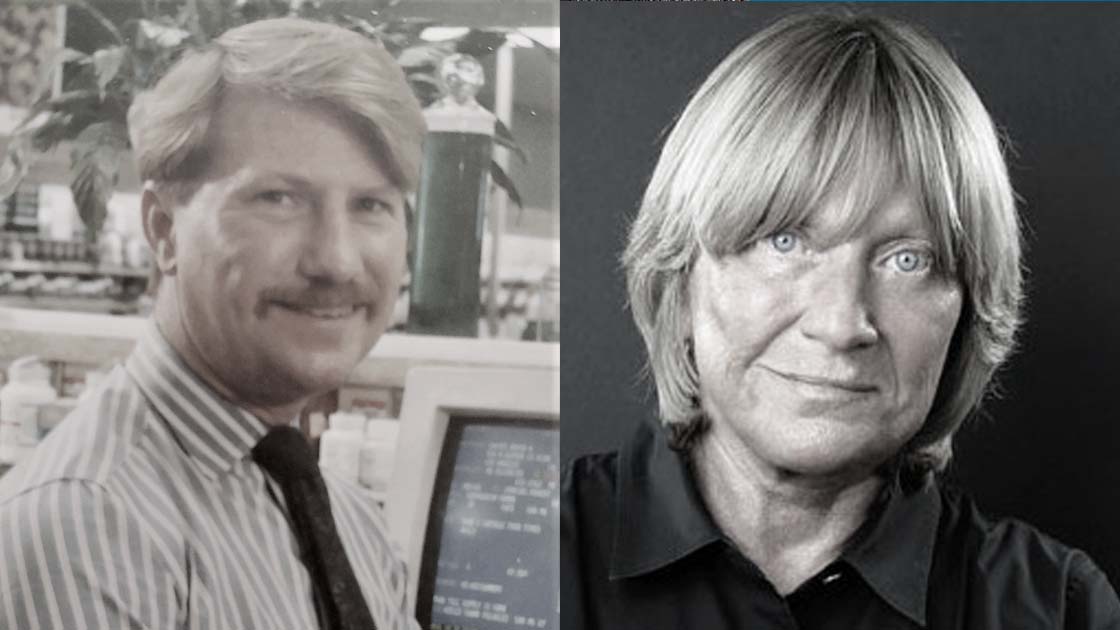

Spotlight: Ruth Tittle, Loyd Tittle & Capitol Drugs

By Irwin M. Rappaport

Ruth Tittle was a founding Board member for the Foundation for the AIDS Monument, and served as Board Secretary for many years. She also served for many years as a board member and officer of the West Hollywood Chamber of Commerce.

In 2017, Ruth received a Rainbow Key Award from the City of West Hollywood. The award was given in recognition of her 16 years of services to the Lesbian and Gay Advisory Board, her work in support of Gay and Lesbian Elder Housing, her service as a board member of the Foundation for The AIDS Monument, her work with her late brother Loyd Tittle as pioneers in affordable prescription services at their pharmacy Capitol Drugs, and for bringing much-needed attention to addiction, mental health, lesbian visibility, preservation of LGBT history, women’s health, and many other aspects and aspirations of the Gay and Lesbian community.

Capitol Drugs Opens

Ruth’s late brother Loyd came to Los Angeles in 1978. In 1986, Loyd purchased a pharmacy called Capitol Drugs, in Sherman Oaks. It was a homeopathic pharmacy. Among other things, Loyd helped customers with supplements that would aid them in recovery from drug and alcohol addiction, based on his own experience as a recovering alcoholic.

In 1990, Loyd opened the West Hollywood location of Capitol Drugs at 8578 Santa Monica Boulevard across from the Ramada Plaza hotel. The business expanded in 1991 to include the Power Zone next door to the pharmacy, offering supplements and a juice bar with smoothies and protein shakes.

Holistic and Personal Approach

Much of the success of Capitol Drugs and Power Zone was due to the way Loyd (and, later on, Ruth) and their staff (including VPs Robert Frydrych and Bruce Senesac) cared for their customers.

Ruth explains: “We knew their spouses, their doctors — each customer was treated like someone you knew and cared about. We took a holistic approach, caring for the whole person.”

By the early 1990s, AIDS was the leading cause of death among Americans ages 25 to 44 and had hit Los Angeles particularly hard. AZT was a single-drug treatment which wasn’t effective when the virus began to mutate, and many people couldn’t tolerate the side effects such as extreme nausea. Often, people stopped taking it because it left them no quality of life.

Organizations such as Being Alive and AIDS Project Los Angeles (APLA) worked with Capitol Drugs to get the latest information to their customers about experimental treatments. They organized lectures in Power Zone and Capitol Drugs, where doctors would talk about the latest experimental treatment options. People would try anything they’d heard might work. They would try garlic enemas, which made the pharmacy smell like an Italian restaurant. Loyd and Ruth grew kombucha mushrooms in a refrigerator and offered Chinese herbs.

Customers would come into the pharmacy and looked like they might not live more than a few days. This was the case with John Duran three different times, according to Ruth, but fortunately he pulled through! Ten friends from Chicago, including Loyd, moved to Los Angeles together but only three survived.

In the early ’90s, Ruth and Loyd would go to four or five memorials a week. Ruth estimates that she lost over 400 friends, customers and employees to AIDS.

Caring for Loyd

Loyd was diagnosed with AIDS in 1988. For four years, Ruth frequently traveled from Lexington, Kentucky to Los Angeles to help care for Loyd, using accrued sick time and paid leave from her government job as a civil engineer.

In 1992, Ruth moved full-time to West Hollywood to care for Loyd and to help him with the businesses. Loyd suffered from cytomegalovirus (CMV) colitis, and as a result he couldn’t absorb nutrition. As with many people with AIDS, this condition led to loss of body mass, commonly known as “wasting.”

Loyd was in the hospital 11 times in his last year. Dealing with insurance companies was a difficult challenge. People didn’t want to lose health insurance coverage, or not be able to get coverage, if the insurer found out he or she had HIV/AIDS.

Ruth wanted Loyd’s insurer to approve paying for a home health care worker, but the insurer denied the request. She learned how to fight with the insurance companies as part of caring for Loyd. With advice from APLA, Ruth finally convinced the insurer to cover home health care because it was much cheaper than the cost of a hospital stay.

As Loyd lay close to death in his apartment, one of his close friends, Steven Bair, came to say goodbye. Steven kneeled down and whispered into Loyd’s ear, “I’ll see you soon.”

Steven died a year later. The last words Loyd said to his sister were: “Ruth, take care of the stores, and I love you.”

Loyd died March 6, 1993, at 42 years old.

“One of the things my brother said is that ‘I don’t want people to forget me.’ And that breaks your heart to hear somebody say that.”

A plaque remembering Loyd is on the sidewalk in front of Capitol Drugs, part of the AIDS Memorial Walk. To deal with the grief from the death of her brother and soulmate, Ruth joined the LA Physicians on AIDS Forum and jumped into work running the pharmaciy. She created and promoted the West Hollywood Health Fair (held in March and October of each year, except during the COVID-19 pandemic).

The Health Fair is an opportunity for local health-conscious businesses to work together and for residents to get healthy and support such businesses. The most recent Health Fair featured more than 70 vendors and attracted more than 2,000 attendees. Later, Ruth became one of the founding members of the Board of the Foundation for The AIDS Monument.

Fear and Discrimination

Drug cocktails (protease inhibitors) finally became available in 1995, and they were a lifesaver, a complete game-changer in the treatment of people with AIDS. But in the beginning, Ruth recalls, there was one mail-order company shipping out the medication for the whole country, and the pharmacy had to send them patient information.

Patients were afraid of losing their jobs or housing if their employer or landlord found out they had AIDS. The company promised that it would send out the medication in a plain brown package directly to the patient, but that didn’t happen — it was marked as being from a pharmacy. It would arrive at workplaces and get left in hallways. The controversy and concern led to a push for patient privacy which ultimately helped bring about the federal law, HIPPA.

The Origins of the AIDS Monument Project

In 2011, Ruth had been on LGAB (Lesbian & Gay Advisory Board, City of West Hollywood) for 12 years, along with Ivy Bottini who had then served on the advisory board for 11 years. Each year, LGAB would pick its top three issues they wanted to work on, but for a number of years, the idea of an AIDS monument didn’t make it into LGAB’s top three.

Ruth wanted to keep pushing the City of West Hollywood to do a monument. Ruth recalls people saying, “We don’t have a cure yet. You’re wanting to build a memorial, but we still need to help people.”

And Ruth thought, “If we don’t do it now, look how long it’s been since all these people died. How long do they have to wait before something is done in remembrance of them?”

“So many times,” Ruth recalls sprinkling ashes “off the coast, because they had nowhere to go, they needed cremation to be paid for, they had … no one to call, no family to come to them … Those are the unspoken, un-memorialized, unmarked graves, unrecognized, that we need to honor. For them.”

So she and Ivy went in to speak to West Hollywood City Councilmember John Duran, who had appointed Ruth to the city’s Lesbian and Gay Advisory Board. Duran said that the city didn’t have the money at the time to build a monument, but that there were “some guys in the community” [Craig Dougherty, Jason Kennedy, Conor Gaughan and Hank Stratton] who had been talking about trying to raise money for an AIDS memorial. He introduced Ruth and Ivy to the men with similar ideas about the monument. [Craig Dougherty wrote a position paper proposing an AIDS monument in 2010, and met with Duran earlier that year].

Ruth, Ivy and a few of the men met at West Hollywood City Hall. At the time, Ivy became focused on another project (senior housing for the LGBTQ community, which would become known as Triangle Square), but Ruth kept working with Craig, Jason, Hank and Conor.

Ruth had worked with Mark Lehman on the Gay and Lesbian Elder Housing project, so she contacted Mark and asked if he was interested in working on the AIDS memorial (now called The AIDS Monument) project. Mark jumped at the idea, and a group of them met at Joey’s Café, located across from City Hall, and hit it off. After that, the Board was formed and started to grow.

Ruth recalled that, while volunteering at a health fair at the Grove, she spoke with a man who told her that his brother died of AIDS. The man didn’t know his brother was sick and he wished he had been able to do something to help.

Ruth told him: “We are building a place where you’ll be able to go anytime you want, and you’ll be able to talk to your brother.”

He said,” I’ll keep watching and when that happens, I’ll be there.”

Ruth sold Capitol Drugs and Power Zone in 2016, 30 years after Loyd opened the first pharmacy location. She currently resides once again in Lexington, KY, near her daughter and grandchildren.

At 70 years old, Ruth hasn’t slowed down. At the time, she and her youngest granddaughter had plans to go to the Dominican Republic to swim with humpback whales during migration season in the spring of 2022.