Stories of Resilience

Lawrence Buckley, 1957 -1995

Story & Recording by Chris Creegan

In July 1995, my partner of ten years, Lawrence, left me. He’d been leaving for a while. First his body and then, in the last few months, his mind. Not a sudden parting, more an ebbing away. Like a lingering tide, occasionally he would threaten to come back. But the pull was unstoppable. He had to go.

Every year, I take a brief sojourn from the routine of life to relive his last weekend. A little melancholy, but comforting, too. Perhaps because I’ve been going for 23 years. Some years it approaches like a hazard warning light. Others it seems to catch me unawares. But it always comes. And I always go.

It can’t be said often enough that grief is not something you get over or move on from. The intensity doesn’t change, only the frequency. It can be random, sparked off by the mention of a book, a place, or a piece of music. But there’s nothing random about this weekend. It comes round again. Right on time.

A friend in the throes of very new grief asked me recently how I got from Lawrence’s death to the joyousness of my marriage to Allan last year. Almost an exam question, that. Hard to answer, no matter how well you’ve revised. My stumbling response was that I got here for Lawrence. He wanted me to thrive, not just survive.

But as I came away, I thought of something else. I didn’t get here by forgetting. I came here by way of remembering, too.

DJing at Eagle’s Nest

Read by Susan Morabito

Story by Jimmy Perigny

Jimmy’s story first appeared on The AIDS Memorial on Instagram

Hi, my name is Susan Morabito, DJ and producer. And I’m pleased to share this story from Jimmy Perigny about his days of DJing at the Eagle’s Nest — a former bar known for low lighting, leather, and Levi’s — on the Westside Highway at 11th Avenue and 21st Street.

Jimmy wrote:

Here is a story I would like to share on World AIDS Day. When I was hired as the Friday resident DJ at Eagle Nest in New York City in 1994, I was forbidden by the owner, Jack Modica, to play any disco or any music from the club the Saint. One night, I sneaked on The Main Event Barbra Streisand extended version at around midnight.

Jack ran into the booth and ripped the record off the turntable and proclaimed, “You are not allowed to play any disco, because it reminds people of the sad deaths from AIDS.”

I responded, “If I didn’t play any song that reminded anyone of AIDS, there would be no music to be played.”

He thought about it and later agreed. So I struck a deal to play only one song after the bar stopped serving … the last song. Patrons mostly stayed to hear my last song, which was a tribute to the Saint and our friends we danced with that passed on.

* * * *

Jimmy’s story reminds me of a similar one I experienced from the mid-90s, when Michael Fierman was playing the Pavilion one night at Fire Island Pines. He was playing a song called “Move Your Body (Elevation), which was big back then. The dance floor was packed. He then slammed into “Don’t Leave Me This Way” by Thelma Huston, a song from 1977. There was a notable shift on the dance floor.

Dozens of younger guys fled, and just as many people ran to the dance floor, but they were over 35-ish. As I was moving towards the dance floor, I walked past these two guys and one said to his friend, ” What is he playing this for? They’re all dead.”

That comment captured the vibe on the island for several summers. During those days, I never felt the dance floor so divided.

West Hollywood Aquatics 1982

Story and Recording by James Ballard

There are not a lot of us left who were there at the beginning of West Hollywood Aquatics in 1982. Our numbers have grown thin, especially for those of us who seroconverted in the early days of what was then was called the gay plague. My name is James Ballard, and I am one of those survivors.

I am blessed with the remembrances of a team that used joy, compassion, courage, and love to fight against a virus that silently spread for years before it was given a name and started taking lives. This is our history as I know it.

Our team was first known as West Hollywood Swim Club, but in many aquatic circles we were dismissed at the onset as “that fag team.” Back then, abuse at meets was not whispered, it was shouted — at least until the races ended and the results were posted. No, we didn’t win every race, but we won more than enough to make it hurt, and we wanted to make it hurt every time another team called us out for being gay.

Looking back, I’d say we found a fair amount of joy in being aggressively gay, because we were building more than a team. We were building pride and an environment where no one need apologize for living out loud. That light still shines.

It would be years before we zeroed in on National and World Masters records, but we could see the possibility, if only we could stay in the water and stay alive. You see, at the beginning, none of us knew that our world had already changed, that a virus was taking hold of our lives. Colds grew into pneumonia, what seemed like bruises became Kaposi sarcoma, and fear spread. There was no test to detect the virus.

We had been working out at E.G. Roberts, a Los Angeles city pool on Pico Boulevard where we had a permit, but our eviction came without notice. The pool manager didn’t want us spreading our disease even though no one knew how it spread or even what caused the disease.

It was like facing a tidal wave in the dark. We lobbied LA City Hall and the LA County Supervisors with very limited success. We took workouts where we could find them, moving from pool to pool. We were constantly searching.

Where could our openly gay team find workout space, and how much chlorine would be dumped into the pool before we walked on deck?

We were rarely welcomed, and we wondered whether our team would survive. November 29th, 1984 changed that. West Hollywood incorporated into an independent city and the next year we were given a home in the old pool that lived below where STORIES: The AIDS Monument now stands. Yes, the pool deck was cracked and the tile needed repair, but it didn’t matter. It was our home and with every lap, we sang a little louder and prayed a little harder.

To us, the space where the AIDS Monument now stands will always be sacred. The smiles and the talent and the souls that lifted us up live on here, and I see the tall bronze Traces as spires rising from the light in the water that connected us with hope and the strength to swim the next mile and believe tomorrow was possible.

By the time we moved to the old pool in West Hollywood Park, we knew it was a virus. Medical researchers, however, offered no promise of a treatment.

The disease was relentless. We grieved and we cried as we said goodbye to the teammates we loved. There was no reprieve as the virus continued to take its toll. The grief overwhelmed us as we wondered who would be next. Most of us knew we could be next. No one felt safe, but in diving into the water we could escape and feel the beauty of living.

It became our freedom. Swimming was living.

We started reading the names of those we lost at swim meets, but those lists were always incomplete. So many simply disappeared. We hoped they had gone home to be with family, but we knew that home was a door that would never open for so many. And year after year, we read more names and remembered.

The lessons we learned was we had to form our own family because who else would understand? We did not turn away, and through it all, new members stepped up. The gay male team gave way to the team of everyone. It was magical. We lived with acceptance, and those who joined gave us hope and proved that change was possible.

Now four decades later, we have not lost the faith. We swim in a new pool that has a view of the bronze Traces, and we know they will carry the light of our team into the heavens. We will not forget. We are West Hollywood Aquatics.

A Life Shaped by HIV/AIDS

Story & Recording by Louis Buchhold

My name is Louis Buchhold, and I live in West Hollywood, California. My entire adult life has been shaped by HIV and the AIDS crisis. It has done things to me and for me I would have never chosen had I not been gay and HIV positive.

The early talk about a mysterious gay disease didn’t scare me. I was young and horny and full of wanderlust. I was one of those beautiful young men you may have encountered on Santa Monica Boulevard, a runaway from the Midwest, in a life resembling a John Rechy novel.

Before my young adulthood bloomed, I took a wild ride through a world that soon came apart around us. The generation of free love I grew up in had turned to free death. I watched everyone in my life fall to the disease and die.

I was a lucky one. I only had minor and treatable opportunistic infections.

I became an art director at Liberation Publications and oversaw the national bi-weekly magazine, The Advocate. It was a hot time for everyone trying to get the latest information about AIDS, what the government was doing or not doing about the epidemic, about support services, about hate crimes, and details on organizations like ACT UP and how they were making the world aware of what was happening to us.

I vividly recall the growing AIDS quilt photos and stories I laid out – probably the only information small-town gays saw. I felt I had an important function to our community at that time, and it pushed me forward.

At a point the terror on the streets was deafening, and things became so grim. Funerals and wakes were turned into parties set up by the deceased only weeks or days before their death, and strictly intended to be fun memories of and for our friends and lovers. It was too much to think about the corroded decimated shells the disease left behind.

One good friend, Wade, had been a clown, a very sensitive and happy man who believed in the power of laughter and loved nothing more than to make people smile, volunteering his time all over LA. He was a son of fame, born in LA privilege – the privileged family who threw him out, disowned him and left him to the streets, where he was eaten from the inside out by Candida, an opportunistic infection. It was a ghastly way to go. He went through it without family, in County Hospital, only loved by us AIDS outcasts. It was better for his high-profile parents if he died forgotten.

A week after Wade’s ugly demise, all his friends met at his memorial margarita party he arranged. I was loaded. I was so loaded in those days just to make it through. It took a lot to hold back my fear and hatred and agony from all the loss and death. I stood in front of Wade’s photo with my margarita, surrounded by his adoring friends, my friends. I fell apart at the seams, crashed onto my knees and couldn’t catch my breath.

How could such a thing happen to such a beautiful man? How could the world allow, or even sanction, the death of my entire generation of gay men?

All my friends were dead or dying. My youth was stolen. I couldn’t hold onto it. I saw my future: like so many of my kind, I would meet my end alone on the street.

Someone lifted me up and took me home, and the daily drinking continued without a pause. The world hurt too much. Eventually I received my diagnosis and death date, summer of 1997. And like others before me, I tried to drink myself away before the unthinkable happened. Unfortunately, I appear to have pickled myself instead – and wasn’t able to die. I only preserved eternal pain and woke up one day laying in the street in Cathedral City at 40.

Similar to Wade’s memorial, a man pulled me up and drove me to AA. It is there I re-started my life, having mostly no fond memories of my youth. But my health struggle didn’t stop with cleaning up. In 2008, I came home from the hospital to die from complications of HIV/AIDS. I didn’t want to die alone trapped in a hospital bed. I wasn’t expected to live past that week. Miraculously, I lived, my work apparently not completed.

I’m 22 years sober today and over 17 years undetectable on medication. I’m a psychologist in Counseling Psychology, and a licensed Marriage and Family Therapist. I work in rehabilitative counseling and recovery.

A Mother’s Unconditional Love

Story & Recording by Aaron Holloway

I never even told my mother I was gay and she didn’t know. While lying there in what I perceived to be my deathbed, I thought that my mother would abandon me. She never did.

I was a graduating senior at Prairie View A&M University in Texas and on my spring break visiting my mother when I was diagnosed with AIDS and end-stage renal failure. When I arrived home, I was greeted very warmly by my mom. Her retirement party was that night. Over the weekend, my health continued to deteriorate. On March 10, 2008, the anniversary of my father’s passing four years prior, my mom insisted on taking me to the emergency room. She drove us to the hospital, where I was born and where my father passed away. I was beyond terrified.

After check-in and having my vitals taken, the nurses began taking several laboratory tests. Within 24 hours, I was checked into the hospital and had an AV fistula implanted into my heart. I was diagnosed with end-stage renal failure. The nephrologist assigned to me was shrewd and proclaimed that my kidneys were “gone” and I would never urinate again.

The same general physician I saw previously in the presence of my mother informed me about my AIDS diagnosis, and thereby outed me — twice. I will never forget what that physician said to me.

“Wake up! It’s AIDS. Are you surprised?”

Miraculously, during one of my dialysis treatments over that summer, my kidneys regained their proper function. I was able to return to my undergraduate studies.

In May 2009, I graduated cum laude from Prairie View A&M University with Bachelor of Business Administration in Management degree. I also graduated cum laude from Texas A&M University – Commerce with a Master of Science in Technology Management degree.

Daniel Warner (1955 – 1993)

Story & Recording by Mark S. King

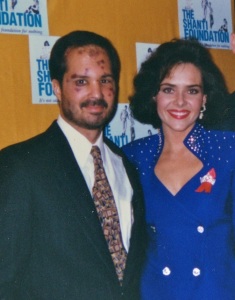

It wasn’t easy keeping my composure when I interviewed for my first job for an AIDS agency in 1987. Sitting across from me was Daniel P. Warner, the founder of the first AIDS organization in Los Angeles, LA Shanti. Daniel was achingly beautiful. He had brown eyes as big as serving platters and muscles that fought the confines of the safe sex t-shirt he was wearing.

I’m Mark S. King, a longtime HIV survivor.

At 26 years old, with my red hair and freckles that had not yet faded, I wasn’t used to having conversations with the kind of gorgeous man you might spy across a gay bar and wonder plaintively what it might be like to have him as a friend. But Daniel did his best to put me at ease. He hired me as his assistant on the spot, and then spent the next few years teaching me the true meaning of community service.

As time went on, Shanti grew enormously but Daniel’s health faltered. He eventually made the decision to move to San Francisco to retire, but we all knew what that really meant. I was resigned to never see him again.

In 1993, Shanti hosted our biggest, most star-studded fundraiser we had ever produced. It was a tribute to the recently departed entertainer Peter Allen, lost to AIDS, and the magnitude of celebrities who came to perform or pay their respects was like nothing I have ever seen. By that time, I had become our director of public relations, and it was my job to corral the stars into the media room for interviews.

Celebrities like Lily Tomlin, Barry Manilow, Lypsinka, Ann-Margret, Bruce Vilanch, and AIDS icon Michael Callen were making their way through the gauntlet of cameras to the crowded media room. And then one of my volunteers approached me with a look of shock and excitement on his face. He pulled me from the doorway.

“I didn’t know he was going to be here,” he said with wide eyes. “I mean –“

“Who?” I asked. Oh my God. Tom Hanks? Richard Gere?

“He’s with Miss America, Mark,” he said. “They’re right behind me.”

We both turned as the couple rounded the corner of the hallway. They entered the light of the media room and I barely kept a gasp from escaping.

Beautiful Leanza Cornett, who had been crowned Miss America, in part, by being the first winner to have HIV prevention as her platform, had a very small man at her side. His head bore the inflated effects of chemotherapy, which had apparently done little to stem the lesions that were horribly visible across his face, his neck, his hands. His eyes were swollen nearly shut. In defiance of all this, his lips were parted in a pearly, shining smile that matched the one worn by his gorgeous escort.

I stepped into the media room, wanting to collect myself, to wipe the look of pity off my face. I swallowed hard and stepped into the doorway to announce them to the press.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” I said. “Miss America 1993 Leanza Cornett, escorted by Mr. Daniel Warner, co-founder of the Los Angeles Shanti Foundation.”

“Ladies and gentlemen,” I said. “Miss America 1993 Leanza Cornett, escorted by Mr. Daniel Warner, co-founder of the Los Angeles Shanti Foundation.”

The couple walked into the bright light and several flashes went off at once. And then the condition of Miss America’s companion dawned on the camera crews. A few flashes continued, slowly, like a strobe light, and across the room a few of the photographers lifted their eyes from their equipment to be sure their lenses had not deceived them.

Daniel looked to me with a graceful smile, and it became a full, sunny grin as he looked to the beauty queen beside him and put his arm around her. She pulled him closer to her. Their faces sparkled and beamed – glorious, joyful, defiant – in the blazing light of the room.

That man, I thought to myself, that brave, incredible man is the biggest star I have ever seen.

And then the pace of the flashes began to grow as the photographers realized they were witnessing something profound. The couple walked the path through the room and toward the other door.

“Just one more, Mr. Warner?” one suddenly called out.

“Miss America! Just another?”

The room became a cacophony of fluttering lenses and calls to look this way and that, all of it powered by two incandescent smiles.

Daniel and Leanza held tight to each other, their delight lifted another notch as they basked in their final call. Every moment of grace, every example of bravery and resilience I have known from people living with HIV, can be summed up in that glorious instant of joy and empowerment.

“Boss,” I said to him as they exited the room, “I didn’t know you would be here. It’s just… so great.”

He winked at me.

“I’ll be around,” he said. “I brought my whole family with me tonight. I need to get to the party and show off my new girlfriend!”

The three of us laughed, and then I watched Daniel and Miss America, arm in arm, disappear down the hall and into the reception.

Only months later, I received a phone call.

“Mark, this is Daniel,” said a weakened voice. “Monday is my birthday, and I thought that might be a good day to leave.”

Daniel had always been fiercely supportive of the right of the terminally ill to die with dignity and on their own terms. We shared some of our favorite memories of our days at Shanti, and I was able to thank him for his faith in me and setting into motion a lifetime of work devoted to those of us living with HIV.

Daniel P. Warner, as promised, died on his birthday on Monday, June 14, 1993. He was 38 years old.

* * * * *

This story is an edited version of the essay “The Night Miss America Met the Biggest Star in the World,” which Mark S. King published in March 2015 on his website, My Fabulous Disease. Photo credit: Leanza Cornett and Daniel Warner by Karen Ocamb.

Rev. Dr. Stephen Pieters: Survivor & Trailblazer

(1952-2023)

Recording (2022) by Jessica Chastain

Story by Irwin M. Rappaport

The Rev. Dr. A. Stephen Pieters is an AIDS survivor, an AIDS activist and a pastor who ministered to people with AIDS from the earliest years of the AIDS epidemic. Steve received his Master of Divinity Degree from McCormick Theological Seminary in 1979 and became pastor of the Metropolitan Community Church in Hartford, Connecticut.

In 1982, Steve resigned his position as pastor in Hartford and moved to Los Angeles. A series of severe illnesses in 1982 and 1983 eventually led to a diagnosis in 1984 of AIDS, Kaposi’s Sarcoma and stage four lymphoma. One doctor predicted he would not survive to see 1985.

And yet, 1985 proved to be a watershed year for Rev. Pieters. He became “patient number 1” on suramin, the first anti-viral drug trial for HIV which led to a complete remission of his lymphoma and Kaposi’s sarcoma. Unfortunately, suramin was found to be extremely toxic, and it came close to killing him twice.

Also in 1985, during his suramin treatments, he appeared via satellite as a guest on Tammy Faye Bakker’s talk show, Tammy’s House Party, on the Bakkers’ PTL Christian network. Tammy Faye took a huge risk with her evangelical Christian audience by inviting Pieters on the program and advocating for compassion and love for gay people and people with AIDS.

I’m Jessica Chastain, and portraying Tammy Faye in her interview with Rev. Steve Pieters was one of the highlights of my role in the 2021 film The Eyes of Tammy Faye. The interview was done via satellite because of fears that the PTL crew would not be comfortable with an in-person interview.

Steve told People magazine that: “She wanted to be the first televangelist to interview a gay man with AIDS. It was a very scary time and there was still a lot of fear about AIDS and about being around a person with AIDS. And I thought the opportunity to reach an audience that I would never otherwise reach was too valuable to pass by. I’ve had people come up to me in restaurants and tell me, ‘That interview saved my life. My mother always had PTL on, and I was 12 when I heard your interview, and I suddenly knew that I could be gay and Christian, and I didn’t have to kill myself.'”

Tammy Faye’s support for people with AIDS and the gay and lesbian community continued. Bringing

along her two children, she visited AIDS hospices and hospitals, went to LGBT-friendly churches, and

participated in gay pride parades.

When the Bakkers’ PTL network and Christian amusement park were embroiled in scandal and she became the subject of jokes and Saturday Night Live skits, she said in her last interview, “When we lost everything, it was the gay people that came to my rescue, and I will always love them for that.”

Tammy Faye passed away from cancer in 2007, but Rev. Pieters continues to thrive both personally and professionally. He has served on numerous boards, councils, and task forces related to AIDS and

ministering to those with AIDS, and his series of articles about living with AIDS was collected into the

book I’m Still Dancing. For many years, Pieters served as a chaplain at the Chris Brownlie Hospice,

where he discovered a gift for helping people heal into their deaths.

Pieters was one of twelve invited guests at the first AIDS Prayer Breakfast at the White House with U.S. President Bill Clinton, Vice President Al Gore, and the National AIDS Policy Coordinator in connection with World AIDS Day 1993, and President Clinton spoke about Rev. Pieters in his World AIDS Day speech on December 1, 1993.

Pieters has been a featured speaker for AIDS Project Los Angeles and his story is told in the

books Surviving AIDS by Michael Callen, Voices That Care by Neal Hitchens, and Don’t Be Afraid Anymore by Rev. Troy D. Perry. He has received many awards for his ministry in the AIDS crisis from

church organizations, the Stonewall Democratic Club in Los Angeles, and the West Hollywood City

Council.

In 2019, his work in AIDS Ministry, including his Tammy Faye Bakker interview, became part of the LGBT collection in the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. Pieters left his position with UFMCC AIDS Ministry in 1997, earned a masters’ degree in clinical psychology, and worked as a psychotherapist at Alternatives, an LGBT drug and alcohol treatment center in Glendale, California.

Now retired, Pieters is busier than ever with speaking engagements, interviews, and finishing up his memoir. He has been a proud, singing member of the Gay Men’s Chorus of Los Angeles since 1994.

* * * * *

Steve Pieters passed away on July 8, 2023, at age 70. Pieters’ memoir, Love is Greater than AIDS: A Memoir of Survival, Healing, and Hope, was published posthumously in April 2024.

I had to Fight for My Right to Work

Story and Recording by Andrea de Lange

I’m Andrea de Lange and this is my story about what happened to me starting in 1987, when I tested positive for HIV.

I was 23. My boyfriend and I had been living together for a year, and we called each other “soulmates.” But HIV is a litmus test for whether someone really is a soul mate, and John failed miserably.

He treated me like a leper every single day! I was afraid of being single, so I tolerated his rage and cruelty for the next two years. Finally, I kicked his ass out.

All that abuse hacked away at my self-esteem. The support of my friends and family helped me through that scary and stressful time. Being a full-time college student at Cal State Northridge and doing a lot of public speaking and interviews also helped. It rechanneled my pain and fear into ways I could benefit others.

Dr. Tilkian gave me hope that I could stay healthy. I became involved in alternative treatments through holistic healers I met at Louise Hay’s weekly Hayrides and at Marianne Williamson’s Center for living. I became healthier than ever.

This helped me separate myself from all the fatalistic dogma medical sources and the media were imposing on anyone HIV-positive. We were slapped with timelines: supposedly, we could remain asymptomatic for up to five years. Then we’d get AIDS, and succumb to a nightmarish death, within two years. AZT helped fulfill that prophecy, usually much quicker than the timeline.

I got my Bachelor’s in Art, then completed a Master’s program in counseling. While doing an internship, I bought a ’52 Packard from a friend; then side-hustled as a driver and extra on the film Ed Wood. Johnny Depp’s bodyguard and driver became my husband.

Ben and I moved to Albuquerque, and I worked in the HIV field over the next four years. My career was great. But my marriage? Not so much. I ended it after three years. And that, along with several other stressful things, led to my burn out.

I knew of the New Mexico School of Natural Therapeutics, and I completed the school’s six-month, 750-hour program for massage therapy. I returned to LA as a nationally certified massage therapist, and picked up a permit application. It was insulting to learn LA Police Commission was in charge of certifying massage therapists – but it got worse. Applicants needed to submit a doctor’s letter stating they were HIV- and Hepatitis C- negative!

I knew the U.S. Supreme Court added HIV to the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1997. The LA Police Commission was messing with the wrong HIV+ massage therapist.

I contacted the HIV & AIDS Legal Services Alliance, and they provided me with a lawyer. The Police Commission was funded by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, so Brad Sears and I literally made a federal case about it.

Our grievance ended after a year, and we won. The commission had to remove all discriminatory wording from permit applications and send permits to anyone previously denied one because of HIV or Hep C. Plus, they had to conduct HIV educational trainings for their staff.

Recently, Brad told me he cited our case in another discrimination case. That is one of many things that make me think it was all worth it.

Wayland Flowers (1939-1988)

Recorded by Mario Cantone

Story by Karen Eyres

Wayland Flowers, who became famous on TV for creating and voicing the sassy puppet Madame, was one of the first openly gay entertainers to find acceptance in mainstream America. When breaking into show business as an actor proved unsuccessful, Flowers began performing in bars and clubs as a puppeteer and comedian. It was during this time he created the now legendary and influential character “Madame.”

I’m Mario Cantone from Sex and the City and Just Like That, and I know a little something about sassy comedy.

After refining his cabaret act throughout the 1960s, Flowers – and Madame – debuted on The Andy Williams Show, a long-running TV variety hour. From there, Flowers became a regular presence on network TV — although it was not unusual for Madame to get more closeups. Madame was gaudy, glamorous, and bitchy… a queer icon. With an act that included edgy jokes and social commentary, Flowers began to garner mainstream success with appearances on hit TV shows such as Laugh In, The Merv Griffin Show, and The Johnny Carson Show. When Paul Lynde left Hollywood Squares in 1979, Flowers and Madame took over the center square.

Flowers offered prime-time television audiences the attitudes of 1970s-era gay men taking their first steps towards Gay Liberation, a point of view that could have been regarded as controversial and provocative to mainstream audiences. Flowers managed to do it without worrying about the network censors, because the dialogue was coming from a dummy.

By the end of his career, Flowers had won two Emmy awards, and had played such venues as the Radio City Music Hall, the Universal Amphitheater in Los Angeles, the Sahara Hotel in Las Vegas, the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis, and the Warner Theater in Washington, D.C. In 1983, he authored the book Madame: My Misbegotten Memoirs.

Sometime in the early 1980s, Flowers was diagnosed with HIV. His performing career came to an end on September 2, 1988, when he collapsed during a show at Harrah’s resort in Lake Tahoe. Several days later, Flowers was flown by air ambulance to make one last visit to his hometown of Dawson, Georgia. Then he returned to Los Angeles, where he checked into the Hughes House, an AIDS palliative care facility.

Flowers died on October 11, 1988 at the age of 48. His publicist originally reported the cause of Flowers’ death as cancer. In keeping with his request, Flowers was cremated and his ashes were interred with his dummy, Madame, in Cedar Hill Cemetery in Georgia.

POZ magazine: Help, Hope, and HIV

Story and Recording by Sean Strub

I’m Sean Strub, and in 1994 I founded POZ magazine with the tagline “Help, Hope, and HIV.”

Hope was important. At the time, not many people believed there would be many survivors, if any, of the epidemic. And while the media context at the time was AIDS was inevitably fatal, dread disease, terminal illness, no treatment, no cure, no survivors – I was living in a world full of people with HIV who were living vibrant lives, raising their children, making art, going to school, creating businesses, engaging in activism, going to demonstrations, caring for others, despite this tremendous health challenge that was likely and only did kill most of us.

It was important to show the example of people who were leading vibrant and full lives, despite that challenge – especially for people who were culturally and geographically isolated and didn’t have the option of going to an ACT UP meeting in the Village and being surrounded by that kind of support.

At the time when we started the magazine, we had a number of, sort of, rules. When we had science coverage, we made sure that a person with HIV was quoted in the first few paragraphs of the story. We didn’t want to hear just from scientists or just from the clinicians; we always wanted to hear from people with HIV themselves.

We sought to make stars. We put people on the cover no one had ever heard of. They weren’t famous; that’s not why we put them on the cover. They were doing really important and inspiring work, and we wanted to bring attention to what it was that they were doing.

The idea of the magazine was to strengthen our community, foster empowerment, resistance and pride, and give that example of survival and hope to people anywhere who read the magazine.

Our first issue featured Ty Ross on the cover. Ty was a very attractive young man who was the grandson of famously conservative presidential candidate Barry Goldwater. He was interviewed by Kevin Sessums, who at the time was the top celebrity interviewer for Vanity Fair magazine. Hollywood photographer Greg Gorman took really great pictures of Ty, added to the appeal.

Frank Rich was a columnist for the New York Times, and he called POZ “easily as plush as Vanity Fair, and against all odds, the only new magazine of the year that leaves me looking forward to the next issue.”

We were criticized, even for the fact that we had high production values and glossy paper and beautiful photography. As if somehow people with AIDS had to have a publication on newsprint with typos, or something. I never understood that criticism. At the time, the publisher of The Advocate said to a trade publication he didn’t understand why anyone would ever advertise in a magazine with such a grim topic.

In those first years, every month, we ran my lab work — the actual scan of the report from NetPath or Quest or whatever the lab was — and explained each of the different things on it. And then we had different physicians and experts comment on my health.

One of my very favorite ones was when my CD-4 count was down, I think, to 1 and my viral load was in the millions. And one doctor looked at my health records and said: Sean is in very serious shape, he is at great risk at becoming ill, and what he needs to do immediately is A, B and C.

In the next paragraph was a different doctor, also an expert, and said: Sean’s situation is dire, but what he shouldn’t do is A, B or C. He should be doing X, Y and Z.

And it wasn’t about trying to call out one doctor or the other. That was the reality at the time is that people were getting conflicting advice even from people who were expert and well-meaning, because so little was known about how best to treat the disease and the opportunistic infections that arose from it.

We were also very focused on the Clinton administration and their failure to support syringe exchange programs when the science was utterly clear that they were incredibly effective at reducing HIV transmission. And that became a campaign that went on for several years. And we were a thorn in their side.

Bob Hattoy, who worked in the White House, used to surreptitiously report to me what people were saying at meetings when the topic came up or things about the epidemic came up.

A year or so after we started, my health had really plummeted. I had spent the money I had saved in my life; I’d sold my insurance policies to fund the magazine. My CD-4 count was almost non-existent, I had pulmonary Kaposi’s sarcoma in my lungs, and I had lesions all over my body. But we carried on, and we found a path through to a point where POZ became the most trusted information source for people with HIV.

In survey after survey, done by us or by government agencies or even the pharmaceutical industry, found that people with HIV trusted POZ more than they trusted even their own personal physicians or any non-profit organization. The only category of information source that they trusted more were their personal friends who were also living with HIV.

In 2004, I sold the magazine and it found a new life online with a much broader audience around the world.

I’ve done a lot of things in the epidemic. I was involved with ACT-UP, co-chaired the fundraising committee, raised a lot of money. I was at demonstrations at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, climbing on the top of Jesse Helms’ house, putting a giant condom over it, working with the People With AIDS Coalition in the early ‘80s even before ACT UP was around, running for Congress as the first openly HIV-positive person to do so in 1990. I produced David Drake’s hit play The Night Larry Kramer Kissed Me, and in 2014, I published a memoir called Body Counts.

But POZ holds a very special place in my heart, because of what it came to mean to so many millions of people living with HIV and affected by HIV in the U.S. and around the world. And I’m proud that it endures and our community endures.

Alvin Ailey (1931-1989)

Written by Irwin M. Rappaport & The AIDS Memorial

Recorded by Debbie Allen

Alvin Ailey’s dance choreography grew out of his early childhood in segregated rural Texas in the 1930s. He and his mother worked as domestic servants and picked cotton, moving from one town to another to find jobs. His famous works — Blues Suite and Revelations — portrayed dance, blues music, the church, and nighttime parties as a diversion for Black people from their daily lives of drudgery.

In his words, “I wanted to explore Black culture, and I wanted that culture to be a revelation.”

I’m Debbie Allen, and I met Alvin Ailey my freshman year in college at Howard University when I went to the New London Dance Festival, and he changed my life — he and his entire company. I was trained with him, I learned his repertoire. And they wanted to take me on the road, but he said I was too young.

When I met him, I knew where I needed to go.

In 1949, Alvin Ailey studied at Lester Horton’s Dance Studio in Los Angeles, one of the early schools in the United States with a racially diverse group of students and teachers. That experience underscored for him the importance of a dance company whose artistic work and composition celebrated Black culture and reflected the diversity of America. When Horton died unexpectedly in 1953, Ailey, who had only joined the company as a dancer that same year, took over as artistic director and choreographer. As a dancer, he performed in the Broadway shows House of Flowers starring Pearl Bailey and Diane Carroll, and Jamaica starring Lena Horne and Ricardo Montemagno. He also toured with Harry Belafonte, but Ailey felt the need to have his own company.

In 1958, he formed the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater after realizing that the work of other choreographers didn’t satisfy his expressive needs as a dancer. Although his early works were critically acclaimed and successful, the company struggled to book performances in its first 10 years.

His company’s international tours in the 1960s, sponsored by the U.S. State Department, were marked using the derisive term “ethnic dance.” The FBI reportedly surveilled the tours and threatened the company with bankruptcy if Ailey or his work on tour exhibited effeminacy or homosexuality, which they called “lewd and criminal.”

A successful tour of Russia in 1970 saved Ailey’s company, which he had announced would close that year. That tour was followed by a sold-out booking at a Broadway theater soon thereafter. Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater became the resident company at New York City Center.

Although he reflected the African American experience in his dance, Ailey disliked being labeled a “Black” choreographer. He hired dancers based on talent and character.

“My dancers must be able to do anything,” he said. “I don’t care if they’re black or white or purple or green. I want to help show my people how beautiful they are. I want to hold up the mirror to my audience that says: This is the way people can be. This is how open people can be.”

His company performed not only Ailey’s nearly 80 works of choreography, but also the works of many other choreographers. Ailey created works for other major arts companies. A dance school, the Alvin Ailey American Dance Center, opened in 1969, and is now called The Ailey School.

Among the honors bestowed on Ailey are the Guggenheim Fellowship, a Spingarn Medal from the NAACP, the Kennedy Center Honors, and a posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom, America’s highest honor for a civilian. He was inducted into Chicago’s Legacy Walk and San Francisco’s Rainbow Honor Walk.

Known for being a very private person, he was not open about his homosexuality. Although he died of AIDS at the age of 58 on December 1, 1989, the cause of his death was attributed to a blood disorder so that his mother would not suffer the stigma associated with a death from AIDS.

Alvin Ailey, we applaud you. We salute you. We will forever speak your name. You left for so many of us — millions of people around the world — a pathway to be courageous, to be creative, to be free, to be, to be.

Pride Tirade 2021

Story and Recording by John Kelly

Happy as I limp my wrist in pride for us — the outcast, the maligned, the persecuted, the entrapped, the murdered, the sweated, the followed, the avoided, the violated, the blackmailed, the serial-tattooed, the sneered, the ostracized, the erased, the hated, the invisible, the raped, the tolerated, the patronized, the parodied, the joke, the denigrated, the evicted, the diminished, the emasculated, the de-promed, the expelled, the therapized, the shock-treated, the lobotomized, the numbed and the drugged, the lost, the dead, the erased, the removed from tangible history, the persistent dwellers in blessed proximity, the survivors, the warriors, the steadfast, the persistent, the inclusive, the non-ageist, the color blind, the expansive, the essential, the imaginative, the true, the warriors, the activists both stewing and shout spewing, the long term survivors demanding to be honored, the generational glue that is gold, the striving and striding toward our place in the sun that demands to be respected, and the imperative that we acknowledge that the AIDS pandemic ruptured our inter-generational dialogue, and our personal, systemic, collective and more generally cadenced growth.

This/MY generation of artists — and OUR audiences — disappeared.

YOU are standing on our generational, grave–like, culturally curtailed, and tribally intrinsic sinkhole. You may be afloat and faring ok on the gravitas of a vast family of ghosts and heart shattering loss, of dead young unresolved spirits. Advance, as we had done, in your own way and manner, and as you continue to grow and transform the world, please aim to bless the ground on which you re-trace our analog step.

WE walk the very same path.

AIDS Project Los Angeles: A Typical Day

Story & Recording by Stephen Bennett

Hello, my name is Stephen Bennett, and I was Chief Executive Officer of AIDS Project Los Angeles in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, which was a very dark period as there was no hope, there was no treatment for people with HIV, and there was so much fear in the world and fear in our community. And hate. And it was a really tough time.

APLA began with an information hotline, and just emergency basic health for people who found out they were sick. It expanded quickly into a food bank, case management, buddy programs, public education and a very sophisticated hotline system.

I want to tell you a story about a morning at work that gives you a slice of what life was like. So, it was early on in the morning, and I was going to work. Our building — the windows were shot out — meaning warnings — and graffiti was put on the wall saying, “We hate faggots,” “You deserve to die.” All kinds of really vulgar and ugly things. And we really didn’t want our clients coming to their place of safety and refuge to see it.

So, we put a Teflon paint on the building and we put bulletproof windows in, and every morning we had a company come and power wash the building. So I went early, because I wanted to make sure that the building was cleaned and looking good and the contractors were doing what they were supposed to be doing.

So I got there, and as I was about to enter the building — there was a little alcove for the front door was – and lying there was a young man, a 16-year-old, and his clothes were torn and he was asleep.

And I said, “Hey, you got to get up, you got to get moving.”

And he woke up and said, “I don’t know where to go. I don’t know who to talk to.”

But he told me he lived outside of Lincoln, Nebraska, and he had come home from school, told his mother he was gay.

She said, “No, you’re not. You cannot be. Go to your room, and don’t tell your father.”

He heard his father come in. His mother and father argued. His father came up to the room and beat him and beat him and beat him. And threw him out the second-floor window. He fell to the ground, he passed out, and he woke up a number of hours later. He walked to the farm nearby, got $100, hitchhiked into Lincoln, and took the bus from Lincoln to downtown Los Angeles.

He then arrived at three o’clock in the morning and walked the seven miles from downtown to the AIDS Project building on Romaine, and curled up on the front door, hoping to be found.

He said that he didn’t know anybody that was gay, but he had read in People magazine about the AIDS Project’s Commitment to Life event, and he knew there had to be gay people there, and he was hoping somebody gay would find him and rescue him. That was the world we were living in.

So, I took him over to the Gay and Lesbian Center. There was a lesbian at the desk who was just fantastic, and she hugged him and told him that they had a place for him.

While this was happening, one of our client’s mother was trying to reach him at home, and she hadn’t been able to reach him for two or three days. And so she went over to see him, and early in the morning, she was quite concerned – he had been very ill, very sick.

And she knocked on the door. Nobody answered. She unlocked it, she came in and found her son. He had taken a gun and blown his brains out. And they were splattered all over. The place was a mess.

Of course, she was very torn up. She didn’t know what to do, so she called his case manager at AIDS Project – Bill, one of our best case managers.

He went immediately and tried to comfort her and figure out what they were going to do. During that time, emergency workers wouldn’t care for us when we were injured, and mortuaries wouldn’t have us in their mortuaries. So they were dealing with that.

At the same time, out in Simi Valley, which is about an hour and a half from here, a young man got up, he was living with his sister, he was quite sick. He lost his home, he had lost his job. He was living there with his sister, and his sister was pretty tired of it.

And she told him, “You get on a bus, you go to APLA to their food bank, and you come back and you bring something home with you. You bring some food back.”

He took the bus from Simi Valley into — over the hill into Granada Hills, and then another bus to Studio City, and then another bus over the mountain into Hollywood, down to our building on Romaine. Well, you can imagine what this was like for somebody who was feeling just terrible.

So he gets to our offices. We had a volunteer there, an older woman who was like our mother, and she would take the kids — the men — when they came into the building and hug them and wrap them in a blanket to keep them warm.

He got very sick while he was waiting in the lobby. They had to take him to the bathroom and change his clothes and wrap him up. There he lay, waiting for his case manager to come in, and his case manager didn’t show up and didn’t show up and didn’t show up. And he felt so lost.

Well, his case manager was at the apartment with the mother and her son who had killed himself, and he had been trying to find a mortuary that would come and get the body, and he couldn’t find one. And finally, they found some guy in Sylmar that if they paid in cash, he would come get the body, but they had to have everything wrapped up in big double-plastic black bags.

The guy said, “I won’t touch this body. I won’t have anything to do with this body.”

And so they were putting the body in these bags, and so they were waiting for the mortuary to come. Finally, the case manager comes to the office and sees his client laying there on one of our couches in the lobby, sobbing. He picks up the client in his arms. The client was very sick, had lost lots of weight, was pretty light – and he carried him to his office to sit him down and talk to him. And when he kicked open his office door, the door squeaked.

After this kind of morning, Bill had had it. This was the last straw, and he totally flipped out. I’m upstairs in my office, Bill comes into my office. He starts screaming and knocking stuff off my desk, and very upset.

And I said, “What in the hell is going on with you?”

And he said, “My door squeaks.”

I came around the desk, gave him a hug, and we went downstairs to the supply room, and I got some WD40, and we went to his office. He told me the entire story of his day. The day went forward.

I spent the day in staff meetings, talking about testing, talking about when we’re going to see a treatment. And then I went to cocktail parties and dinner to raise money. And that was a day in the life of one of our case managers and for me, the CEO of the AIDS Project, at the height of the AIDS epidemic.

Spirituality, Medicine, and Art

Story & Recording by Vasilios Papapitsios

My name is Vasilios Papapitsios. I became HIV-positive when I was 19, in North Carolina, through barebacking. The first five years I lived with HIV, it’s like I was stuck in a vacuum. I couldn’t breathe.

In 2011, three months after my diagnosis, I was expelled from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill under homophobic claims that I was the center of the local HIV outbreak. This was simply not true.

The school told me I was a threat to campus and banned me from stepping foot on the grounds. This caused me serious mental health issues which forced me into a dark place for many years. I even went to the ACLU for assistance, but decided not to put up a fight, because that meant disclosing to the public and to my family.

I didn’t get on antiretroviral treatment because I had little accessibility to care and stigma made me fear taking my next steps. I got really sick. At one point, I was reduced to 104 pounds and 6 CD4 or immune cells. I should have had thousands of those little warriors. My doctors told me I had one to three months left to live, if left untreated.

There I was. staring death in the face. But I made a new start, through spirituality, medicine, and art.

I did an exercise in transmutation with my mentor, Sharon Jeffers. She’s the grandmother I never had growing up and a true mystic. On pieces of paper, she laid down the words “fear” and “love” in front of me. She had me stand on fear and feel with every particle of my being what that felt like. I saw HIV — the virus, as well as the stigma associated with it — as lead in my body: dense, dark, and heavy.

She then asked me to step forward onto love, and to begin visualizing what loving my HIV would look like. Love was only two feet in front of me, but getting there felt like pushing through a wall of cement.

I thought to myself, “I can love HIV.”

As I moved from fear into love, I visualized darkness turning into something full of light, sparkly and golden, pumping life through my once ‘polluted’ tunnels, now made into a magical network of veins transmitting healing forgiveness inside of me. I made the intention to let go, to breathe, and to finally begin to heal and feel pleasure, to experience joy, and be more fully me, by embracing HIV.

Finally I was ready to start my journey towards a more holistic health. It felt like I was taking a deep breath for the first time in a while.

You might wonder why I avoided treatment for five years, especially when doctors tell us how important it is to start treatment as soon as we test positive. I don’t have an easy answer for you, except to say that lots of bad things happened to me during those five years, and I couldn’t cope.

For starters, I was so poorly educated that I didn’t think things would get as bad as they did. Then there was my struggle to get good medical care in North Carolina after they had defunded the AIDS Drug Assistance Program in 2012, not to mention the ugly layers of stigma and self-stigma.

The important thing is that, shortly after I accepted the virus and stepped out of fear, I was ready to take my meds. Within three months, I had gained 30 pounds and my CD4 cells returned to near normal. My body felt better than it had in years. And I was breathing again.

Which brings me around to the role of art in transforming my life. I am an artist. I make digital art and soft sculptures. Disclosure is one of the most important aspects of fighting HIV stigma, preventing the spread of the virus, and gaining a healthy sense of self.

One day I had this idea. I thought, what if I could use art to disclose my status and help others to disclose theirs? And what if it was light-hearted and cute, not heavy and scary?

I began to embroider weathered jocks and underwear I’d lived in since I contracted HIV. I call this series of artworks “Intimacy Issues.” They are like my magical protective garments and have titles like Love AIDS, I’m Poz, and my personal fave, Poz4pleasure.

I began embroidering my underwear as art therapy, and with each stitch, I felt empowered. Through this work, my fear started to dissipate and I could see myself having an intimate relationship again.

I believe there are blessings and hidden blessings in everything, including HIV. As the great Sufi poet Rumi said, “The wound is where the light enters you.” HIV is but one of many wounds I have, but for me it is where the most light pours through.

Spared, Blessed and Fully Awake

Story by Alexandra Billings

When it happened it was not a surprise. It was not out of left field and it was not unexpected. When it happened it was happening to everyone. Everyone I knew. Everyone around me. A black curtain had been thrown over the heads of us all and smothered us all in a cloud of decaying flesh and bloodied foot prints.

And the stench of the AIDS virus infiltrated the inside of my being and it is still potent. It is still thriving. Because I still have AIDS.

And I have outlived most everyone I knew, and we were in our 20s and we were in our 30s and we were still young and still having sex and still doing drugs and still running and jumping and skipping and singing and being queer. And yet one by one, we were being ticked off like ducks at a carnival. In the heart. In the brain. In the limbs.

And for some unknown reason . . . some of us were spared. And it is daily. And it is not gone. And it is getting worse. And it is still potent and it is still fresh. And it still lives in me and one day it will kill me. I know that.

But I am here and I am present and I am fully awake. And I love my life and I am married to the greatest human on the planet and I have spirits around me that bathe me in light.

And so I am truly blessed. Not that I have this disease, but that I learn from it. I remember very well when it happened. Because it seems like it happened yesterday.

Pedro Zamora, 1972-1994

Recording by Wilson Cruz

Story by The AIDS Memorial and Irwin M. Rappaport

Photo © MTV

Pedro Zamora’s bravery and commitment to AIDS advocacy engaged and educated TV audiences around the world. Pedro was a cast member on Real World: San Francisco from 1993 to 1994. I’m Wilson Cruz, and hardly a day goes by that I don’t remember Pedro’s courage and dedication.

On Real World: San Francisco, Pedro was one of the first openly gay people with AIDS that many people ever saw on TV. Simultaneously, on My So Called Life, I was the first openly gay actor playing an openly gay character in a series regular role on American TV. And to this day, Pedro still inspires me as an actor, as a man, and as an activist.

Pedro Zamora was the youngest of eight children living in Havana, Cuba when his parents decided to emigrate to Florida as part of the highly-publicized Mariel Boat Lift in 1980. Pedro was an honor student, captain of the cross-country team and President of the Science Club at his high school where he was voted Best All Around and Most Intellectual. But at 17 years old, Pedro learned he was HIV positive after donating blood at a blood drive.

His HIV-positive diagnosis propelled him to become a full-time AIDS educator, so that other young people could learn what he was never taught. This led to hundreds of speaking engagements; a front page article about him in the Wall Street Journal; appearances on major talk shows hosted by Oprah Winfrey, Geraldo Rivera and Phil Donahue; and testimony before the U.S. Congress on AIDS education.

Producers of the Real World wanted to cast an HIV-positive person. Being cast on the series gave Pedro his biggest platform for AIDS education and won him fans all over the world. Audiences watched how his HIV status affected his relationships with housemates and his health. They celebrated his commitment ceremony with partner Sean Sasser, which was the first such ceremony in the history of television.

But about midway through the taping of the series, Pedro’s health began to decline, but he told producers that he wanted them to tell his story until the end. When the stress from his conflict with a homophobic housemate, Puck Rainey, led Pedro to want to move out of the Real World house, his other housemates instead voted to evict Rainey. Time magazine ranked that episode #7 of the top 32 most epic episodes in reality TV history.

In late June 1994, the Real World: San Francisco began to air on MTV. At a cast reunion party only two months later in August, Pedro’s progressing illness was evident. He was diagnosed with toxoplasmosis, a disease that causes brain lesions, and also a rare and often fatal virus that causes inflammation of the brain. Doctors estimated that he had 3-4 months to live.

In September 1994, he was transferred to a hospital in Miami near his family. With the help of the U.S. government, the remainder of his family was allowed to move to the U.S., so that they could be with Pedro before he died. MTV paid for his medical costs, because Pedro was unable to get health insurance due to having a pre-existing condition.

Pedro Zamora died of AIDS at age 22, the morning after the final episode of the show was broadcast.

A memorial fund, youth clinic, a public policy fellowship, a youth scholarship fund and a street in Miami are named in Pedro’s honor. He was one of the 50 people first included on the National LGBTQ Wall of Honor as part of the Stonewall National Monument, the first national monument in the U.S. dedicated to LGBTQ history.

Reflecting on Pedro’s death, President Clinton reminded us, “We must remember what Pedro taught us: One person can change the world — and whether or not we are living with HIV or know someone who is, we all have a responsibility as global citizens to do whatever we can. Life is short enough as it is. No one should die from a disease that is both preventable and treatable.”

Tom Rolfing, 1949-1990

Story & Recording by Ralph Bruneau

Dear Tom Rolfing,

It has been such a long time since you’ve been gone. I honor your life, death and the years we spent together. You were my first real love and biggest loss. I am forever in your debt. So much of who I have become is due to our time together.

We were: Summers on Fire Island, cocaine and Scotch, Upper West Side and West Village, sexy boys, quaaludes, Cartier roll rings, Studio 54, ordering in Chinese food, Levis and white tees.

Then AIDS came and we were: Kaposi’s sarcoma, doctors and hospitals, ACT UP, funerals, terror, wheelchairs and hospital beds — and then you were gone.

I want you to know that I’m still here and fighting. I am well and able to love in a way I couldn’t have imagined back then. You are still in my thoughts and in my heart. I think, I hope, that you would be proud of me.

I remember you. I remember us. I love you.

Legacy of Survival

Story & Recording by Brenda Goodrow

When I was 6 years old, my adoptive mother told me I was born HIV-positive. That same year, in 2003, my biological father passed away from AIDS-related complications. His family still believes that it was non-AIDS related cancer, but my childhood nurse, who also took care of him at the adult clinic, told me that he refused his antiretroviral treatment until he died. Suicide by AIDS. I grew up telling people it was a drug overdose.

When my birth mom, who everyone expected to pass away from AIDS sooner than later, died when I was in high school in 2009, I was finally able to tell people one truth about my parents: My mom was a homeless drug addict who died of hypothermia outside of a hospital in the dead of winter. I always left out the part about her being HIV positive, though. It was easier to keep my secret that way.

It’s taken me a long time to find forgiveness for them; to not view their deaths as them abandoning me to live with HIV on my own. But in my darkest moments of living with HIV, I found compassion for them in ways I never thought I would. I realized they were just humans who were hurting, too, and if they felt anything close to what I have then I understand why my mom kept choosing drugs and my dad chose to not fight for his life.

Ever since going public with my status and sharing my story, I’ve found so much healing in the amount of love, compassion, and understanding people have extended to me.

In my short-term experience with activism, I’ve heard a lot of talk about the term “Long-Term Survivors,” and how that encompasses way more than just our HIV statuses. People living with HIV are also often survivors of abuse, domestic violence, homelessness, drug addiction, mental illness, and so many other things.

Despite everything, both of my parents were fighters until they died, in more ways than one. I am their surviving story and I’m proud of that. I like to think they are, too.

Sylvester, 1947-1988

Recording by Billy Porter

Story by Dave Marez and Irwin M. Rappaport

Sylvester, sometimes known as the Queen of Disco, was famous for an androgynous look and a fierce falsetto voice. Born in the Watts section of Los Angeles on September 6, 1947, he grew up singing in a Pentecostal church but left the church at age 13 and soon after left home after being shunned by the congregation and his mother for being gay.

Refusing to bow to pressure to conform, for his high school graduation photo Sylvester wore a blue chiffon prom dress and his hair in a beehive. He moved to San Francisco in 1970, where he performed for a couple of years with the infamous group of drag performers “The Cockettes.”

He released in a solo album in 1977, performed regularly in gay bars in San Francisco’s Castro neighborhood, and was cast in a cameo singing role in the Bette Midler film, The Rose. It wasn’t until his third album in 1978 that Sylvester found success including his best-known hit “You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real)”. That album, with background vocals from the Two Tons of Fun, Martha Wash and Izora Rhodes, went gold, topped the dance charts in the U.S., and led to major talk show performances and promo tours in the US.

On March 11, 1979, while Sylvester recorded his Living Proof live album in a sold-out show at San Francisco’s War Memorial Opera House, then-Mayor Dianne Feinstein awarded him the key to the City and proclaimed it “Sylvester Day.”

Never forgetting his community roots, Sylvester performed at gay pride festivals that year in San Francisco and London. Another dance hit, “Do You Wanna Funk,” released in 1982, was co-written with Sylvester’s frequent collaborator, writer-producer Patrick Cowley, who died of AIDS that year when the disease was still known as GRID.

Sylvester, along with Joan Rivers and Charles Nelson Reilly, did the first-ever AIDS fundraiser at Los Angeles’ Studio One nightclub in 1982. He called his 1983 song “Trouble in Paradise,” an AIDS message to San Francisco, and performed benefit concerts to raise awareness and money about the epidemic.

Sylvester’s boyfriend at the time died of AIDS in 1987, and Sylvester’s own health began to decline later that year. In the spring of 1988, Sylvester was hospitalized with pneumonia but managed to attend the Gay Freedom Parade in June in a wheelchair.

The Castro Street Fair in October of that year was dubbed “A Tribute to Sylvester.” Although he was too ill to attend, he heard crowds schanting his name from his bedroom and continued to give press interviews, openly stating that he was dying of AIDS and trying to highlight the impact of the disease on African-Americans.

Sylvester James, Jr., died on December 16, 1988 at age 41. At his direction, his body was dressed in a red kimono in an open casket. In his will, he bequeathed all future royalties to two AIDS charities.

In 2005, Sylvester was inducted into the Dance Music Hall of Fame and in 2019 the Library of Congress chose “You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real)” to be preserved in the National Recording Registry.

Growing Up HIV+

Story & Recording by Noelle Simeon

Photo by Julie Ann Shaw

Hello, everyone. My name is Noelle Simeon. I have been living with HIV since I was two weeks old.

Back in November 1982, my mom was attending a routine ultrasound close to her due date. Her excitement of soon meeting her first child quickly turned to dread when it was discovered some of my intestines and other organs were on the outside of my belly, a condition called gastroschisis. An emergency c-section was ordered for a few days later. My birth was complicated, to say the least.

The first year of my life was spent in and out of the hospital with six surgeries and a blood transfusion. The main surgeon didn’t want to go through a possibly lengthy process of getting blood from my immediate family, so he recommended using the hospital’s blood bank. Now, this is a world-renowned hospital with some of the best surgeons, so my parents listened.

A few years later, my parents received a letter stating that because I received a blood transfusion, I should get tested for HIV. When the test result came back positive, the hospital suggested my parents keep my HIV+ status a secret to protect me from being alienated from our family or friends.

Ryan White, the middle school student who was banned from attending his school because he was HIV+, was freshly in the news, so my parents listened … at least for a little while. My mom told a few of her close friends whose girls were in my Girl Scouts troop, which quickly led to the entire troop finding out.

An emergency meeting was called. My parents organized for my doctor and another infectious disease doctor to come and educate the parents and Girl Scout leaders. Although only a few felt uncomfortable with me staying, as they didn’t want their daughters to get attached to someone who was just going to die, my parents chose to take me out of the troop. They didn’t want to stir any trouble.

Eventually, the rest of my family found out about my HIV status. I was loved and cared for, never feeling ostracized or unloved by anyone in my family. They are my biggest supporters to this day, and for that, I am forever grateful.

Growing up HIV+ was very alienating in other ways, however. Due to my health, I didn’t go to regular school and was home-schooled for a large chunk of my childhood. I didn’t attend school until about the third grade, and went to my first public school in seventh grade. Until then, my days were mostly spent by myself unless my cousins or family friends with kids were getting together with my parents.

But my lack of social interaction was changed when my parents found Paul Newman’s Hole in the Wall Gang Camp and Camp Laurel. Hole in the Wall Gang Camp is a camp for children with any kind of disease. It was in beautiful Connecticut, its sole location at the time, and I got to fly by myself for the first time in my life.

I remember thinking how green the ground looked as we landed. Camp Laurel is a camp specifically for kids infected with or affected by HIV/AIDS, so direct family members like my younger sister could also attend.

We didn’t need to worry about remembering to take our medications because the staff and counselors kept track. We could just be kids, and run and play and sing camp songs and ride horses and learn to fish and have our first crush and first kisses and tell campfire stories. They were the best summers of my entire childhood.

At one of these camps, I met a girl who was also blood-transfused with HIV at the same hospital as me. Her name was Anique, and she had been going to Hole in the Wall Gang Camp for a few years. Her last wish was to go for one last summer, and so her parents made it happen.

We had never met before, but there was an instant kinship felt between us. Anique even gave me a present: a cute, stuffed bunny that I named Benjamin. Unfortunately, she didn’t survive the drive back home and passed away.

Hers was the first death I experienced. I remember her coffin was so small, and it scared me without me really understanding why. I was nine. I still have Benjamin.

It was not my last death of kids from camp. I still remember and think of them often. Some of their names are Nathan, Billy, Dawn and Raytasha.

Living with HIV when you’re young is interesting. There is no specific time or incident I really remember, but my mom would explain that I had “special blood,” so if I were to ever fall or get cut, I should not let anyone touch it.

I could never be blood brothers or sisters with anyone. When I was a teenager, my doctors told me not to kiss anyone, as my braces could cause me to bleed.

A very small circle of my friends knew about my HIV status when I was in middle and high school, and a few teachers who I deemed to be “cool.” The stigma surrounding HIV made me reluctant to tell many people.

As I got older, I told more and more friends, growing more and more tired of curbing my conversations and hiding my medications. In 2020, I flat-out went public with my HIV status, posting a lengthy letter on my personal blog and social media. The pandemic made me realize that if I wanted to be protected, then I would have to be honest with everyone I have in my life.

HIV/AIDS affects everyone who has it differently, but there’s this underbelly of shame that is carried with each person. My current therapist has experience with the HIV/AIDS community, and with her help, I’ve been able to let go of some of that shame.

I believe living with any disease creates a kind of continuous trauma of explaining yourself, fighting for your medical rights, and feeling side-effects from treatments and medications.

Therapy has made me see how hard it is even to speak about my feelings about having HIV, as I am never asked how it makes me feel. I’m used to telling my story, but those are all the facts and bullet points, not the emotional tolls or daily consequences that are paid. Even writing this has stirred a lot of uncomfortable feelings.

But, I believe having HIV has given me a strength and fortitude that I wouldn’t have otherwise. The people and experiences and hope I have felt is unbelievable.

Being told for most of your life that it’s a miracle you are even here is very humbling. It makes you want to treasure the blessings and the failures in life, because at least you’re here to fail or succeed, because there are so many who aren’t here any longer.

Elizabeth Glaser, 1947–1994

Ariel Glaser, 1981-1988

Story & Recording by Jake Glaser

“My life had certainly not turned out the way that I expected, but while tomorrow would bring what it would, today was glorious.”

– Elizabeth Glaser, wife, sister, mom and angel

On a Los Angeles summer night, in a chance meeting at a stop light on Sunset Boulevard, Elizabeth Glaser, a second grade school teacher, and Paul Michael Glaser, a television star from Starsky & Hutch, rolled down their car windows and found one another on this spinning rock in the cosmos to create a family whose creation, passion, love, fear, tragedy and sacrifice would change the world.

It was in 1981 when my mother, Elizabeth Glaser, gave birth to our guardian angel, our guide in life, Ariel. While in labor at Cedars Sinai in Los Angeles, my mother hemorrhaged and lost seven pints of blood. In order to save her and her baby, a blood transfusion was necessary, one that would forever change the path of their lives. What began as new virus predominantly showing up in gay men, the Human Immunodeficiency Virus was spreading fast and amongst many communities, not just the homosexual community.

My sister Ariel became sick. She would sink into sickness one week and bounce back the next, signs of what most called an extreme flu, but became known soon after as the global health crisis we now know as AIDS.

It was soon after this that I was born, HIV positive and with an unknown future. After years of antibiotics, and medications never designed for the fragility of a child’s immune system, my sister’s HIV turned into AIDS and took my sister’s life at age 7.

A mother’s response to losing her child is like a crack of thunder across the world. My mother knew she lived with this same virus, and so did I. Her only choice was to do something about it. So she asked for help, used her skills of getting people to come together and work together, and applied it to the start of the Pediatric AIDS Foundation, in an effort to raise essential funds for medical research into pediatric treatments for HIV.

She smashed down politicians’ doors, called Hollywood to action with my father, raised the funds, and built a team of interdisciplinary medical researchers to start asking questions to which we did not have the answers. She used every last bit of her energy to humanize this issue, speaking at the 1992 Democratic National Convention, advocating in Washington, and telling her story to the world in hopes of bringing enough light to this dark place so our future could be bright.

In 1994 after witnessing the creation of the first antiretroviral medications and seeing a step in the right direction, her health declined and my mother passed away at the age of 46, when I was only 10 years old.

The spark that she ignited, lit up the world. Elizabeth Glaser and so many others sacrificed their lives to provide us the opportunity we have now, to create a world free of HIV, to make sure no one dies from this disease and to make sure no child is ever born HIV positive again.

Through the collaborative efforts of The Pediatric AIDS Foundation, a medication that was designed for a different use was applied to stop in-utero transmission of the virus from mother to child. The Pediatric AIDS Foundation has grown into a community health organization in 19 countries, with over 5,500 sites across the globe and over 30 million women reached to prevent the transmission of HIV to their babies.

Today we are not only an HIV-focused family, our programs support a variety of health issues, most recently being COVID-19.

The ripple that Elizabeth Glaser and Ariel Glaser left in this world will forever be reinforced by each and every one of us who choose to do something when we feel we can’t, who choose to run into our fears when we feel helpless and show each other that even when we feel all hope is lost, in the darkest moments in the darkest places in our lives, light will always prevail if we choose to turn the light on.