Stories of Isolation

Ryan White, 1971-1990

Recording by Jim Parsons

Story by The AIDS Memorial

Ryan White (December 6, 1971 – April 8, 1990) was a teenager from Kokomo, Indiana, who was expelled from his school due to his HIV status. He died when he was 18 years old.

White is buried in Cicero, close to the former home of his mother. In 1991, his grave was vandalized on four occasions.

White, a hemophiliac, contracted HIV through a blood transfusion. He was diagnosed in December 1984 and told that he had only 6 months left to live.

Doctors said that White posed no risk to other pupils. However, when he attempted to return to school, parents and teachers protested against his attendance, scared that he could transmit HIV through casual contact.

The dispute made news headlines around the world and turned White into an advocate for AIDS research and education. Although he lived 5 years longer than predicted, he sadly died just one month before his high school graduation.

Over 1,500 people attended White’s funeral on April 11, 1990 at the Second Presbyterian Church on Meridian Street, Indianapolis. His pallbearers included Sir Elton John AIDS Fundation and Phil Donahue. His funeral was also attended by @MichaelJackson.

Sir @EltonJohn performed a song he wrote in 1969, Skyline Pigeon, at the funeral. White also inspired him to create @ejaf.

On the day of the funeral, former President Ronald Reagan wrote a tribute to White that appeared in The Washington Post. This was seen as an indication of how White had helped change the public’s view of HIV AIDS, especially when considering Reagan’s indifference to the virus. By the time he finally addressed the epidemic in 1987, nearly 23,000 Americans had already perished.

Mark Morgan, 1961-1993

Story & Recording by Rev. Dr. Ginny Brown Daniel

My friend Mark Morgan (1961-1993) died of “the flu.” I miss him every day.

He gave me my first job when I was 15 years old in 1986. Mark owned Toomer’s Drug Store in Auburn, Alabama. This was his dream as a pharmacist and a huge Auburn football fan, because the drug store was where we all rolled the oak trees with toilet paper whenever we won a game.

I knew Mark was gay, but we never talked about it because it was the mid-80s in Alabama, and Mark was Southern Baptist. I grieve that I could never talk to him about being gay, but I saw how much he struggled with being a Christian and gay. I assumed that when he was ready, he would share.

Each year, Mark took a vacation to New England. He would tell us about this area called Provincetown and share how much he loved it there. Even then, I knew in the marrow of my being that he went there so that for one week a year, he could truly be as God created him without judgment or shame.

Mark was an active leader in our church and when I was asked to preach the sermon on Youth Sunday, Mark helped me prepare my delivery. I vividly remember practicing my sermon in the sanctuary as he walked down the aisle giving me pointers.

I stopped working at Toomer’s in 1991 but often saw Mark until I heard at Christmas 1992 that he was sick. I really wanted to visit him to tell him my exciting news that I was going to seminary to be a minister. But his parents told me he was in the hospital and was too sick for anyone to visit him. When I asked what he had, they quickly told me and everyone else in town that he had a bad case of the flu.

Mark died on January 5, 1993. I have never said this out loud, but I will say it here in this holy ground of @theaidsmemorial: My friend, Mark Morgan, died from complications of AIDS.

Mark not only shaped my adolescence, he shaped my ministry because I vowed to welcome all in the Church and celebrate that all — especially those who are gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender — are created in God’s image because my friend Mark was created in God’s image!

Albert Delègue (1963-1995)

Story by The AIDS Memorial and Irwin M. Rappaport

A version of this story first appeared on The AIDS Monument on Instagram

Recorded by Gus Kenworthy

French male supermodel Albert Delègue was among the top male models of the early to mid-1990s. Albert grew up in Mérilhu, a small village in Southwestern France where he worked as a ski instructor. But Albert’s days as a ski instructor came to an end when, at age 26 while visiting Paris, a friend introduced him to Olivier Bertrand, the head of modeling agency Success, who signed him.

Bertrand told OK Podium magazine, “I realized immediately that he would become a top model. Two days after we signed him, he was already getting a very important contract.”

Hi, there. I’m Gus Kenworthy, and I won the Silver Medal in slopestyle skiing at the 2014 Winter Olympics. When I came out in 2015, I became the first-ever openly gay professional athlete in an action sport.

Albert entered the modeling world in an era when supermodels were thrust into the international spotlight, becoming celebrities in their own right. Naomi Campbell, Kate Moss, Linda Evangelista, Cindy Crawford, Christy Turlington, Claudia Schiffer, and Tyra Banks were instantly recognizable. Some of the male models who, like Albert Delègue, ascended to stardom in that decade include Mark Vanderloo, Alain Gossuin, Marcus Schenkenberg, Werner Schreyer, Greg Hansen and Cameron Alborzian.

In 1991, Albert secured a multi-year contract with Giorgio Armani estimated to be worth 5 million French Francs. Armani’s 1992 cologne ad featured the iconic Bruce Weber photo of Albert’s face pressed against a woman’s shoulder.

Herb Ritts photographed Albert for Versace in 1991. Albert was the face of other top brands, too: Calvin Klein, Valentino, Rene Lezard, Sonia Rykiel, and Kenzo. But Albert’s career lasted only five years, until 1994.

When Albert died on April 14, 1995, his family reported that the cause of death was a skiing accident that they said had happened eight months earlier and had left him paralyzed in the hospital. However, only five days after his death, their story began to unravel.

French newspaper L’Humanité reported that Albert died of AIDS, and similar reporting came out four days later from Spanish newspaper El Pais, which stated that he died of encephalitis developed as a result of the AIDS virus. Later, his family is said to have intervened with the press and censored any further stories about AIDS as the cause of death.

Fellow model Alain Gossuin thought that it was important to tell the truth about the scourge of AIDS. So when he was interviewed on French TV show “Tout es Possible,” he said that press reports of Albert’s death from AIDS were censored by his family. His interview was edited out of the show.

Homophobia was and still is so prevalent that families like Albert’s, and people living with HIV or AIDS, were and are ashamed to admit that they or their loved ones are HIV-positive or have AIDS.

Can you think of another disease where social stigma would convince parents to lie about their child’s cause of death?

Gia Carangi, January 29, 1960 – November 18, 1986

Recording by Cindy Crawford

Story by Irwin M. Rappaport and Cindy Crawford

Photo by Aldo Fallai for the 1980 Giorgio Arman campaign

Hi, I’m Cindy Crawford. Before the word “supermodel” was coined, there was Gia Carangi.

From her first major modeling job with Versace, she was catapulted to the covers of Cosmopolitan and Vogue magazines, and became a favorite model of many of the world’s best-known fashion photographers, including Helmut Newton, Francesco Scavullo and Arthur Elgort. Arthur first saw photos of Gia in 1978, when she worked behind the counter at her father’s restaurant, Little Hoagie, in Philadelphia.

Gia brought a new dark, edgy, moody look — and an “I don’t give a damn” attitude to American fashion modeling that had been dominated by smiling, blonde, blue-eyed beauties. She was a rebel who unabashedly posed nude when most American models shied away from nudity. She was also a troubled young woman who had been sexually abused at five years old and whose mother abandoned her, her father and siblings for another man.

She was a lesbian who wore black motorcycle jackets, no makeup, and vintage men’s clothing in an era when being homosexual was an act of defiance; a heroin addict who used drugs to deal with her loneliness as a famous young model in New York City with few friends.

The drugs made it harder and harder for her to work. She fell asleep or walked out on jobs. But she was in such high demand that those hiring her would look the other way or enable her behavior rather than helping her or forcing her to deal with her drug addiction.

As former girlfriend Elyssa Stewart told the UK newspaper The Independent: “The problem was that people were more interested in hiding the marks than helping her.”

In 1984, she entered rehab for six months at the insistence of her family, but was soon back on heroin, and by 1985, she was in the hospital with pneumonia. She was sleeping on the streets, she was bruised, had been raped, and was reportedly doing sex work.

She died in November 1986, the first famous woman to die of AIDS and a warning that AIDS was not just a disease that took the lives of gay men. Her death brought attention to the risk of needle-sharing and the benefits of needle-exchange programs and AIDS education rather than demonizing drug users.

Even as troubled as she was, her exit from the fashion industry left a gaping hole and people longed for her dark-haired, brown-eyed beauty. So much so, that when I first came to New York as a young model, my agent sent me out to some of those same photographers, saying they had “baby Gia.” I will forever be grateful to her for opening so many doors for me.

Francesco Scavullo, the photographer who adored Gia even as he hid the sores and track marks on Gia’s arm in a photo shoot late in her life, explained her allure: “Gia is my darling – old, young, decadent, innocent, volatile, vulnerable, and more tough-spirited than she looks. She is all nuance and suggestion, like a series of images by Bertolucci.”

“I never think of her as a model, though she’s one of the best,” he said. “She doesn’t give you the Hot Look, the Cool Look, the Cute Look. She strikes sparks, not poses. She’s like photographing a stream of consciousness.”

Rest in peace, Gia.

Spirituality, Medicine, and Art

Story & Recording by Vasilios Papapitsios

My name is Vasilios Papapitsios. I became HIV-positive when I was 19, in North Carolina, through barebacking. The first five years I lived with HIV, it’s like I was stuck in a vacuum. I couldn’t breathe.

In 2011, three months after my diagnosis, I was expelled from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill under homophobic claims that I was the center of the local HIV outbreak. This was simply not true.

The school told me I was a threat to campus and banned me from stepping foot on the grounds. This caused me serious mental health issues which forced me into a dark place for many years. I even went to the ACLU for assistance, but decided not to put up a fight, because that meant disclosing to the public and to my family.

I didn’t get on antiretroviral treatment because I had little accessibility to care and stigma made me fear taking my next steps. I got really sick. At one point, I was reduced to 104 pounds and 6 CD4 or immune cells. I should have had thousands of those little warriors. My doctors told me I had one to three months left to live, if left untreated.

There I was. staring death in the face. But I made a new start, through spirituality, medicine, and art.

I did an exercise in transmutation with my mentor, Sharon Jeffers. She’s the grandmother I never had growing up and a true mystic. On pieces of paper, she laid down the words “fear” and “love” in front of me. She had me stand on fear and feel with every particle of my being what that felt like. I saw HIV — the virus, as well as the stigma associated with it — as lead in my body: dense, dark, and heavy.

She then asked me to step forward onto love, and to begin visualizing what loving my HIV would look like. Love was only two feet in front of me, but getting there felt like pushing through a wall of cement.

I thought to myself, “I can love HIV.”

As I moved from fear into love, I visualized darkness turning into something full of light, sparkly and golden, pumping life through my once ‘polluted’ tunnels, now made into a magical network of veins transmitting healing forgiveness inside of me. I made the intention to let go, to breathe, and to finally begin to heal and feel pleasure, to experience joy, and be more fully me, by embracing HIV.

Finally I was ready to start my journey towards a more holistic health. It felt like I was taking a deep breath for the first time in a while.

You might wonder why I avoided treatment for five years, especially when doctors tell us how important it is to start treatment as soon as we test positive. I don’t have an easy answer for you, except to say that lots of bad things happened to me during those five years, and I couldn’t cope.

For starters, I was so poorly educated that I didn’t think things would get as bad as they did. Then there was my struggle to get good medical care in North Carolina after they had defunded the AIDS Drug Assistance Program in 2012, not to mention the ugly layers of stigma and self-stigma.

The important thing is that, shortly after I accepted the virus and stepped out of fear, I was ready to take my meds. Within three months, I had gained 30 pounds and my CD4 cells returned to near normal. My body felt better than it had in years. And I was breathing again.

Which brings me around to the role of art in transforming my life. I am an artist. I make digital art and soft sculptures. Disclosure is one of the most important aspects of fighting HIV stigma, preventing the spread of the virus, and gaining a healthy sense of self.

One day I had this idea. I thought, what if I could use art to disclose my status and help others to disclose theirs? And what if it was light-hearted and cute, not heavy and scary?

I began to embroider weathered jocks and underwear I’d lived in since I contracted HIV. I call this series of artworks “Intimacy Issues.” They are like my magical protective garments and have titles like Love AIDS, I’m Poz, and my personal fave, Poz4pleasure.

I began embroidering my underwear as art therapy, and with each stitch, I felt empowered. Through this work, my fear started to dissipate and I could see myself having an intimate relationship again.

I believe there are blessings and hidden blessings in everything, including HIV. As the great Sufi poet Rumi said, “The wound is where the light enters you.” HIV is but one of many wounds I have, but for me it is where the most light pours through.

Ed Junior, 1982-2015

Story & Recording by Dave Coleman

Ed Junior had the voice of an angel, but only those of us involved in the karaoke scene of southern California got to hear it. Affectionately known by his friends as Rihanna, he could match the best singers of our time like @WhitneyHouston, @CelineDion, @Siamusic and Freddie Mercury.

But Ed had a secret that he kept from his friends: He was in the United States illegally. This explained why he never had a good job that lasted for long and why he never had a bank account. It also explained why he never sought medical attention after being diagnosed with AIDS. He didn’t have medical insurance, and thought he’d be deported back to Mexico and outed to his family.

Ed was too afraid to enter a hospital until the disease deteriorated his body so badly that he was collapsing and couldn’t hide it any longer. Friends admitted him into the hospital. He wasn’t deported. He never left the hospital. A few weeks later, he was dead.

As Ed laid on the hospital bed dying from AIDS, I would play his favorite songs for him, like Rihanna, “Shine bright like a diamond / Find light in the beautiful sea / I choose to be happy.”

Ed’s family came to the United States to claim his body. A celebration of Ed was held at his favorite gay bar to raise money for funeral expenses, where we all tried to sing in his memory. His family came and met all of Ed’s friends. They shed tears for the loss of their child, but also happy tears for the amount of love this tight knit community had for this angelic human being.

Ed’s voice and kindness touched all of our lives. He will be remembered always. He shone bright like a diamond in our sky.

Tested

Story & Recording by River Huston

I’m River Huston and this is my HIV story, which I call “Tested.”

Claude taught people how to sing. He was charming and sweet. We started to hang out. We did not have sex. But we did make out a lot.

One day he asked me if I would be willing to go with him to take an HIV test. It was in a flirty way, like if we take this step together, we would be making some kind of weird commitment.

I didn’t know anything about HIV, but I couldn’t possibly have it. At the time, I’d been clean and sober five years. I could run eight miles without any effort. I did yoga every day and ate brown rice. I knew what AIDS looked like from the guys in the Village. I saw the emaciated men, covered in sores, walking with canes and toting oxygen tanks. I knew people from Narcotics Anonymous who had had AIDS, but it was a secret thing. No one talked about it. I had never heard of a woman who had AIDS.

I said yes. It was May 1990. We went to the Department of Health and had our blood drawn. We joked and were relaxed. They told us to come back for our test results in ten days.

I sent up a few prayers to cover my bases. I had struggled with God most my life. I had grown up agnostic. I made up a God that I called Harry when I was a child. He was useful for when I was in trouble. I decided there was no God when I started using drugs at 12. It was simpler that way.

Later, in recovery programs, they talked about a higher power. I never understood it. It was silly to believe with such abandon in what seemed to be a fairy tale. But I needed something to hold onto. I made a decision to just have faith. I didn’t believe in anything specific, but I had faith there was something.

The 10 days preceding our test results were filled with a simple prayer, “Please do not let this test be positive.” I hummed it silently like a mantra. And as Claude and I headed up to Harlem on the A train to the Department of Health, I hummed, “Please do not let this test be positive.”

We were excited and nervous. I was ready to go further with Claude than with anyone else I had met. He seemed real. He was not an addict, had a loving family. He was normal. I was almost normal, or I could appear normal. I worked, I went to college, tried to learn social skills, participate in society.

I had spent most my life living on the edges of civilization, not exactly legal, but not hurting anyone. I grew weed in the ’70s in Humboldt County, I lived in a van, played music in the streets. I roamed the country, selling my body along the way since I was 15. I made the leap into the world of conformity when I got sober at 25. I often felt like an interloper in the so-called real world.

We took our seats in the clinic. The testing had been anonymous. I fingered the piece of paper with my number on it as if it was a winning lottery ticket. We were the only ones in the waiting room.

They called his number first. I waved, “Bye, honey.” Then it was my turn, and I followed the doctor into a small room.

She smiled at me, but looked tense, almost scared. I sat down. She was sitting across from me staring at the folder. Finally, she looked at me and said, “Your test came back positive.”

I couldn’t quite grasp this.

“Is this good?” Knowing it wasn’t.

She said “no” and explained to me that I was HIV-positive.

Then my denial kicked in. My voice trembled when I said, “They make mistakes, right? We should take another test. I’m sure this is mistake.”

She explained they had done both the Western Blot and the Eliza test. “You have this virus in your bloodstream.”

I felt like I was in a horrible car accident where the car rolls over and over and all you hear is the sound of metal against metal, then silence. And somehow, you get out of the car. Physically, you have survived, not even a scratch, but the world as you see it is no longer the same. I couldn’t hear a word she was saying. I stared out the window at broken glass that littered the asphalt beneath an empty swing set.

“Why did you ever think it would get better? You don’t deserve anything. You’re a piece of shit, and you’ll always be a piece of shit. Damaged goods, garbage, a pariah.”

These thoughts paraded along with, “You will never have children, you’re going to die alone, diseased and untouchable. I fucking hate you, you stupid piece of shit.”

The doctor broke through my barrage of self-loathing when she said, “Listen, according to everything you told me in the last visit, you have a good few years left.”

I started to cry. I cried the way you do when you can’t stop. After a few minutes, I looked up. She handed me a box of tissue with a sad face. I felt dizzy and sick. The walls seemed to close in on me. I couldn’t stand to be in that room another second.

I pulled on my sunglasses and I walked out without another word. Walked right past Claude. I couldn’t even look at him, I felt so ashamed and dirty. I headed for the door, went down the stairs to the street, and started to run.

I cut through the kids on the sidewalk that were getting out of school and the moms with their baby carriages. I just wanted to get to the train. I wanted to go home, I wanted to hide under the covers. I wanted to forget this day ever happened. I finally reached the train as it pulled into the station. I got on and the doors slid shut. I stared straight ahead, shaking, numb, nauseous. I felt someone slide next to me. I turned my head, and it was Claude.

He had this look on his face. The fucking look I would come to dread for the next 30 years, the look of pity. He was out of breath from running.

He leaned over and said, “River, it’s going to be okay.”

I wanted to scream. “It’s not okay, and it will never be okay, and okay is over.”

But I didn’t say anything. I stared straight ahead. The train stopped and went, and stopped and went. The wall I started to build around me was impenetrable. Claude lapsed into silence. We exited together at Union Square. We climbed the stairs to the street.

With a weak smile, he said, “If you need anything …”

He gave me a quick, awkward hug. He went his way, and I went mine. End of my relationship with Claude, beginning of my relationship with HIV.

At 61, HIV has been the only constant in my life. I’ve done amazing things, wrote books, painted paintings, traveled the world, did a one-woman show. I also spent many years sick, in beds, in hospitals, poked and prodded, alone, depressed, in enormous physical and psychological pain.

I tried so hard to not define myself by HIV, even if the world continues to define me as diseased. I have walked this journey alone with as much kindness and love I can muster for myself. But mostly I’m just waiting to die.

Max Robinson, 1939-1988

Recording by Don Lemon

Story by The AIDS Memorial and Irwin M. Rappaport

Max Robinson was an inspirational figure for me when I decided to become a TV journalist and news anchor. I’m Don Lemon, and Max’s professional ascent to become, in 1978, the co-anchor of ABC World News Tonight on ABC News, alongside Peter Jennings and Frank Reynolds, showed me that it was possible for a Black American to become a news anchor on a major network.

Many people aren’t aware that Max was the first to reach that height in our business, and was also a founder in 1975 of the National Association of Black Journalists. He mentored and supported other Black journalists and technicians trying to work their way up the ladder in a White-dominated news business. Sadly, however, Max struggled with alcohol, and died of AIDS on December 20, 1988, at the age of 49.

After growing up in segregated Richmond, Virginia, Max’s first news anchor job was for a Portsmouth, Virginia, TV news station where – and this seems unbelievable now – he had to recite the news from behind a screen, so that viewers didn’t know he was Black. One day, he pulled down the screen and the station was flooded with complaints, leading to his firing the next day.

But Max rebounded, and in 1966, he was hired as a reporter at Channel 4, the NBC affiliate in Washington, DC, and became a regular guest on Meet the Press. He won an Emmy award for the documentary series The Other Washington, portraying life in Anacostia, a Black section of Washington, DC known for crime and poverty, and showed how discriminatory laws perpetuated poverty and inequality in healthcare and education.

Max moved to Channel WTOP in 1969 and later moved up to co-anchor the nighttime newscasts at 6:00 p.m. and 11:00 p.m. But being the first Black man in his position at a series of jobs apparently took a toll on his mental health and self-esteem.

“I can remember walking down the halls and speaking to people who would look right through me,” Robinson is quoted as saying in the book Contemporary Authors. “It was hateful at times … I’ve been the first too often, quite frankly.”

Famed Watergate journalist Carl Bernstein, who was ABC’s Washington bureau chief in 1980-1981, claimed that Max was deliberately excluded from any decision-making regarding the newscast he co-anchored. Max publicly complained about racism at the network, including at a Smith College speech in 1981.

After Frank Reynolds died in 1983, Robinson was a no-show at the funeral where he was supposed to sit next to First Lady Nancy Reagan. He claimed he had had too many drinks, couldn’t sleep, took some prescription drugs, and didn’t wake up on time the next morning. Soon thereafter, Peter Jennings was named the sole anchor of World News Tonight, and Max was moved into a weekend anchor position.

The next year, Max left ABC to become anchor at a local NBC-owned station in Chicago, but often failed to show up at work, entered rehab for alcohol abuse, and retired in 1985. The autobiography he was writing with the help of Chicago Tribune columnist Clarence Page was never finished.

My CNN colleague Bernard Shaw observed: “Max, at the time of his death, had more arms around him than he had when he was fighting lonely battles fighting racism in the industry, fighting the things all of us deal with in our personal lives.”

AIDS in Prison, and My Lost Brothers

Story & Recording by Richard Rivera

My name is Richard Rivera, and I remember how devastating AIDS was in the New York State prison system. It was much worse than the public realizes or would imagine.

All around me during the early 1980s, prisoners began to experience sudden weight loss, sores in their mouth, a persistent cough, and other inexplicable medical problems. Popping up on the news were rumors of “that gay disease.” Its official name was Gay-Related Immune Deficiency, or GRID. But no one really knew what was going on or how it was transmitted. All we knew was that this new thing was a death sentence.

Ironically, despite our fears and superstitions, prisoners continued to do what prisoners did. Intravenous drug use, tattooing, and high-risk sexual behavior remained the norm.

In 1985, concerned over a friend named David who had disappeared from general population, I convinced one of the nicer officers to sneak me into the infirmary for a visit. When the doors opened, I saw a dorm-like area with beds neatly made with hospital corners lining the wall like a military barrack. But the room and the beds were empty.

The officer pointed to the back of the room, which was much darker. I made my way to an area sealed off with Plexiglas. It had an additional eight beds, on which eight prisoners lay: some on their backs, others in tight little balls. Their eyes were sunken into their skull, their hair thinning; their arms looked like twigs and their fingers were impossibly long. Some of them were covered in sores. One had swollen, purple legs, the skin so tight it looked like ripe fruit. He was softly moaning. It was my friend David.

I met David in 1983 at Great Meadow Correctional Facility, aka “Comstock.” Prisoners called it “Gladiator School,” because of its propensity for violence. I was 17 when I arrived. I couldn’t read or write, and I had no friends and reputation. I got into so many fights that I lost count after the fifth month there.

It was after a particularly violent encounter that I met David. He took me under his wing, showing me who to avoid and what not to do, while encouraging me to wear my glasses and stop eating my fingernails. I had no more trouble at Comstock. But David had a history of intravenous drug use and, I suspected, continued using and sharing needles.

In 1984, I was transferred to Green Haven Correctional Facility, and David followed soon after. He arrived smaller, thinner, and not at all the strong, robust, confident man I remembered. Then a few months later, David was transferred. That’s when I heard rumors of the secret ward and went looking for him.

The conditions in that ward were deplorable. Porters almost never went in to clean, medical staff rarely visited, and officers refused to have any contact with them at all. There were no medications, with the exception of the over-the-counter stuff like cough syrup and Motrin. AZT was still years away.

But every week from 1985 to 1987, I went there to care for David and the other men. David’s condition worsened, and ultimately, he was transferred to St. Agnes Hospital in White Plains, where he died.

The reason I am here today is because of brothers like David — and Jamel and Mongo and Joe and Pierre and Larry — who cared for me, corrected me, encouraged me, nudged me along the way. I went looking for David in that ward, because men like him had saved me, too, from being broken.

Debbie Lynn Kellner, 1964 – 2004

Story & Recording by Crystal Gamet

My Mama, Debbie Lynn Kellner, August 2, 1964 – January 20, 2004.

My beautiful mama, who never knew she was beautiful and never got that message from this world.

I wish that I could tell her how beautiful she was. Losing my mother was like losing part of my own body. I compiled some pictures to share a little bit about who she was.

She was a woman who was born into extreme poverty to a family of ten. She was blessed to be a twin and have that incredibly deep connection in this world.

My mom could not read or write, and she suffered more physical violence than I can ever bring myself to describe — but she survived longer than the men who tried to kill her. She fought to graduate from high school, despite the incredible bullying she experienced for being in the special education program.

My mom contracted HIV at 21 and was convinced she would never have access to romantic love again in her life. This was partially true.

So when she met Tom, he had just been released from prison and he was homeless, so he immediately moved in with us. Even though that got us kicked out of public housing, my mom was willing to overlook that, because at least she had someone who loved her.

Her ashes are buried with him, and I still find this fact sickening.

She survived to the age of 39. She survived the early years of the AIDS epidemic, despite chronic poverty, domestic violence, stigma and depression.

She loved all of my friends. and to the friends who were brave enough to show her love at the end when they knew she had AIDS, I will never forget. I am grateful for how hard to she fought to live long enough to help me grow into the almost-woman I was when she died.

I will miss her forever.

round the corner now

Outside the dawn is breaking

But inside in the dark

I'm aching to be free

The show must go on'

Freddie Mercury, 1946-1991

Recording by Adam Lambert

Story by Irwin M. Rappaport

Hi, I am Adam Lambert, and I am so honored to tell Freddie’s story and to bring the music of Queen to audiences around the world.

Rock legend Freddie Mercury was a singer, songwriter and pianist who is best known as the front man for the band Queen. Freddie was born in Zanzibar on September 5, 1946. He grew up in India and moved to the UK in 1964.

Early in his music career, he sold second-hand clothing and was an airport baggage handler while singing with a series of bands until forming Queen in 1970 with guitarist Brian May and drummer Roger Taylor.

Praised by Roger Daltry, lead singer of The Who, as “the best virtuoso rock ‘n roll singer of all time,” Freddie Mercury was known for his flamboyant stage persona and four-octave vocal

range. As a songwriter, he wrote 10 of the 17 songs on the band’s Greatest Hits album, including “Bohemian Rhapsody,” “Somebody to Love,” the rock anthem “We Are the Champions,” “Don’t Stop Me Now,” and the rockabilly hit “Crazy Little Thing Called Love.” Other Queen hits include “Another One Bites the Dust” and “Under Pressure,” a collaboration with David Bowie.

The band was famous for its live concerts, including an unforgettable performance at Live Aid in 1985, and broke records with the size of its audiences. Queen was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2001 and the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 2003. The band sold over 300 million records.

The citation for Queen in the Rock Hall of Fame proclaims that, “In the golden era of glam rock and gorgeously hyper-produced theatrical extravaganzas that defined one branch of ’70s rock, no group came close in either concept or execution to Queen.”

Freddie publicly admitted to having gay sexual experiences and had a series of romantic relationships with both men and women, and described himself as bi-sexual. His larger-than-life stage persona contrasted with a shy, sensitive personality when not performing. And he rarely granted interviews.

Rumors that Mercury was sick with AIDS began in 1986 and dogged him for the rest of his life, although his HIV positive diagnosis was actually in 1987. He became increasingly thin, and the band stopped touring. His final performance with Queen was in 1986, and his last public performance was in Barcelona in 1988.

In 1990, the band was in Switzerland recording Innuendo, their last album with Freddie. Freddie was committed to recording as many vocal tracks as possible while he still had the energy to do so – an incredible feat of creativity and powerful vocals, even as his body was failing.

In an interview with Express, Brian May recalled Freddie’s recording of the song “The Show Must Go On”:

“When I gave him the final version to sing, it was like taking the lid off a bottle that was about to explode.”

The song includes these haunting lyrics:

“I’ll soon be turning, round the corner now

Outside the dawn is breaking

But inside in the dark I’m aching to be free

The show must go on

The show must go on

Inside my heart is breaking

My makeup may be flaking

But my smile, still, stays on.”

On November 23, 1991, he issued his first public admission of his illness:

“Following the enormous conjecture in the press over the last two weeks, I wish to confirm that I have been tested HIV positive and have AIDS. I felt it correct to keep this information private to date to protect the privacy of those around me. However, the time has come now for my friends and fans around the world to know the truth and I hope that everyone will join with me, my doctors

and all those worldwide in the fight against this terrible disease.”

Freddie Mercury died the very next day, at age 45.

In Remembrance of Those Who Were Alone

Story & Recording by Cosgrove Norstadt

In 1981, I was living in Ohio and dating a man from New York City. Because of him, I became aware of a strange cancer striking gay men in New York and San Francisco. Unfortunately, in Ohio, no one was worried about AIDS because only people in NYC and San Francisco were at risk.

Four years later, I moved to NYC. I met the Reverend Bernard Lynch who was ministering to those afflicted with AIDS. I ask him how I could help. What could a naive youth from Ohio know about such a massive Holocaust? I wasn’t cut out for ACT UP and criticized for my lack of anger and outrage. I wasn’t angry. I was sad. Terribly sad. I was sad for all the men dying alone in the hospitals.

Bernard directed me to St. Clare’s Hospital to volunteer. They wanted me to wear masks and gloves and footies, but I couldn’t. If I was going to hold you in my arms as you died, I was going to let you touch me, cough phlem on me and cry on my shoulder. From a Christ-like point of of view, I could not do less than Christ himself.

Most men at St. Clare’s lasted two weeks, tops. I hadn’t lived in NYC long enough to make friends. My friends became short term and very deep with the men who were alone and dying. I met sex workers who taught me compassion. I met intravenous drug users who taught me to be accepting. Every two weeks, I lost my newest best friend. All of these men shared their most intimate secrets with me and, most of all, their love.

The number of men I held as they died is impossible to calculate, but as my life continues, I remember the patients of St. Clare’s Hospital. I remember how you were ostracized by friends and family. I remember how, as gay brothers, we loved one another unconditionally.

This is my tribute to those who were alone. They had no friends and no family. I was just a 22-year-old boy from Ohio, learning life lessons I wish never existed. I miss all of you, and I continue to remember you and love you.

Nicholas Dante, 1941-1991

Recording by Steven Canals

Story by @The AIDS Memorial and Irwin M. Rappaport

Nicholas Dante was a dancer and writer who is best known for co-writing the book for the smash-hit Broadway musical A Chorus Line. Born Conrado Morales in New York City, he intended to study journalism but dropped out of high school at age 14 because of the homophobia he faced.

He told journalist Jimmy Breslin: “I grew up in the ’40s, a Puerto Rican kid on 125th and Broadway, and obviously gay. Nobody would hang out with me. I was terrified to go out where anybody could see me.”

He worked as a drag queen and began studying dance. He landed parts as dancer in the choruses of musicals including Applause, Ambassador, and Smith.

Dante wrote the book for the smash-hit Broadway musical A Chorus Line, along with playwright James Kirkwood Jr. The show opened in 1975 and was directed and co-choreographed by Michael Bennett, who started developing the musical.

Bennett invited Dante to attend sessions in which Broadway dancers would tell stories about their lives. Bennett chose Dante, along with Kirkwood, to write the story about seventeen so-called “Broadway gypsies” auditioning for eight spots in a chorus line performing behind the lead actors of a Broadway show. The character Paul was based on Dante’s own experiences growing up poor, lonely, and ridiculed, because he was gay.

I’m Steven Canals, co-creator, executive producer, writer and director of the FX drama series Pose. I grew up as a poor Afro-Puerto Rican queer kid in the Bronx, so I can relate.

The music for A Chorus Line was by Marvin Hamlisch, with lyrics by Edward Kleban. The musical was revived on Broadway in 2006 and on the West End in London in 2013. Dante and Kirkwood won a Tony Award for Best Book of a Musical in 1975, and the Drama Critics Circle Award for Best Musical and the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1976. At the time of Dante’s death, A Chorus Line was the longest running show in Broadway history.

During a tap-dance number, the character Paul falls and injures one of his knees on which he had recently had surgery. Paul is carried off to the hospital, and the remaining dancers see how fragile their careers are, they can come to an end without warning.

Nicholas Dante, who based the character of Paul on his own life, died of AIDS in New York City in 1991 at age 49. Director Michael Bennett also died of AIDS in 1987.

As a prelude to the song “What I Did for Love,” a dancer character named Zach asks the rest of the dancers what they will do when they can no longer dance. Their answer is that whatever happens, they won’t have any regrets. When the eight dancers chosen for the chorus line appear on stage to take their final bow, the audience can hardly tell one apart from the other. They have become the nearly faceless background singers of a chorus line.

Nicholas Dante never again attained the success he had as a writer of A Chorus Line, but hopefully he, like those dancers, had no regrets and will forever stand out from the crowd.

The AIDS Atlanta Outreach Team

Story & Recording by Misha Stafford

This story originally appeared in The AIDS Memorial on Instagram.

After graduating from college, I moved to Atlanta, Georgia for my first real job, and I began volunteering for AID Atlanta.

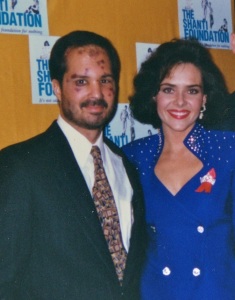

This is a picture of myself with seven of the best friends I ever had, taken in September of 1990. We were trained in an outreach project that gave talks about HIV/AIDS and safe sex.

We spoke at churches — if they would have us. We spoke to schools, civic organizations, local groups — any group that would let us in the door. We came up with a whole routine that had both humor and a very serious aspect to it.

I share this very scared picture of mine, my friends, my Band of Brothers. We were having a cook-out that night and waiting on all of our other friends to arrive when someone snapped this pic. It’s old, it’s not in great shape — but it means the world to me.

We were listening to Roxy Music that night, and the songs “Avalon” and “More Than This” can still take me back to every detail of that evening.

I have ghosted my friends’ images so that those who are too young to remember the early days of AIDS epidemic can maybe understand, just a bit, what it’s like to be the last one left.

In this picture are two high school teachers, one attorney, one in law school, one hairdresser, one college student and one carpenter. They each have their own unique story. By 1997, all had succumbed to AIDS, including my best friend, Phil, and I was the last one left. The only one alive.

I left Georgia after this, taking a position in south Florida. I found that you can change your surroundings, but you still carry the hurt, the loss, and the grief wherever you go.

Growing Up HIV+

Story & Recording by Noelle Simeon

Photo by Julie Ann Shaw

Hello, everyone. My name is Noelle Simeon. I have been living with HIV since I was two weeks old.

Back in November 1982, my mom was attending a routine ultrasound close to her due date. Her excitement of soon meeting her first child quickly turned to dread when it was discovered some of my intestines and other organs were on the outside of my belly, a condition called gastroschisis. An emergency c-section was ordered for a few days later. My birth was complicated, to say the least.

The first year of my life was spent in and out of the hospital with six surgeries and a blood transfusion. The main surgeon didn’t want to go through a possibly lengthy process of getting blood from my immediate family, so he recommended using the hospital’s blood bank. Now, this is a world-renowned hospital with some of the best surgeons, so my parents listened.

A few years later, my parents received a letter stating that because I received a blood transfusion, I should get tested for HIV. When the test result came back positive, the hospital suggested my parents keep my HIV+ status a secret to protect me from being alienated from our family or friends.

Ryan White, the middle school student who was banned from attending his school because he was HIV+, was freshly in the news, so my parents listened … at least for a little while. My mom told a few of her close friends whose girls were in my Girl Scouts troop, which quickly led to the entire troop finding out.

An emergency meeting was called. My parents organized for my doctor and another infectious disease doctor to come and educate the parents and Girl Scout leaders. Although only a few felt uncomfortable with me staying, as they didn’t want their daughters to get attached to someone who was just going to die, my parents chose to take me out of the troop. They didn’t want to stir any trouble.

Eventually, the rest of my family found out about my HIV status. I was loved and cared for, never feeling ostracized or unloved by anyone in my family. They are my biggest supporters to this day, and for that, I am forever grateful.

Growing up HIV+ was very alienating in other ways, however. Due to my health, I didn’t go to regular school and was home-schooled for a large chunk of my childhood. I didn’t attend school until about the third grade, and went to my first public school in seventh grade. Until then, my days were mostly spent by myself unless my cousins or family friends with kids were getting together with my parents.

But my lack of social interaction was changed when my parents found Paul Newman’s Hole in the Wall Gang Camp and Camp Laurel. Hole in the Wall Gang Camp is a camp for children with any kind of disease. It was in beautiful Connecticut, its sole location at the time, and I got to fly by myself for the first time in my life.

I remember thinking how green the ground looked as we landed. Camp Laurel is a camp specifically for kids infected with or affected by HIV/AIDS, so direct family members like my younger sister could also attend.

We didn’t need to worry about remembering to take our medications because the staff and counselors kept track. We could just be kids, and run and play and sing camp songs and ride horses and learn to fish and have our first crush and first kisses and tell campfire stories. They were the best summers of my entire childhood.

At one of these camps, I met a girl who was also blood-transfused with HIV at the same hospital as me. Her name was Anique, and she had been going to Hole in the Wall Gang Camp for a few years. Her last wish was to go for one last summer, and so her parents made it happen.

We had never met before, but there was an instant kinship felt between us. Anique even gave me a present: a cute, stuffed bunny that I named Benjamin. Unfortunately, she didn’t survive the drive back home and passed away.

Hers was the first death I experienced. I remember her coffin was so small, and it scared me without me really understanding why. I was nine. I still have Benjamin.

It was not my last death of kids from camp. I still remember and think of them often. Some of their names are Nathan, Billy, Dawn and Raytasha.

Living with HIV when you’re young is interesting. There is no specific time or incident I really remember, but my mom would explain that I had “special blood,” so if I were to ever fall or get cut, I should not let anyone touch it.

I could never be blood brothers or sisters with anyone. When I was a teenager, my doctors told me not to kiss anyone, as my braces could cause me to bleed.

A very small circle of my friends knew about my HIV status when I was in middle and high school, and a few teachers who I deemed to be “cool.” The stigma surrounding HIV made me reluctant to tell many people.

As I got older, I told more and more friends, growing more and more tired of curbing my conversations and hiding my medications. In 2020, I flat-out went public with my HIV status, posting a lengthy letter on my personal blog and social media. The pandemic made me realize that if I wanted to be protected, then I would have to be honest with everyone I have in my life.

HIV/AIDS affects everyone who has it differently, but there’s this underbelly of shame that is carried with each person. My current therapist has experience with the HIV/AIDS community, and with her help, I’ve been able to let go of some of that shame.

I believe living with any disease creates a kind of continuous trauma of explaining yourself, fighting for your medical rights, and feeling side-effects from treatments and medications.

Therapy has made me see how hard it is even to speak about my feelings about having HIV, as I am never asked how it makes me feel. I’m used to telling my story, but those are all the facts and bullet points, not the emotional tolls or daily consequences that are paid. Even writing this has stirred a lot of uncomfortable feelings.

But, I believe having HIV has given me a strength and fortitude that I wouldn’t have otherwise. The people and experiences and hope I have felt is unbelievable.

Being told for most of your life that it’s a miracle you are even here is very humbling. It makes you want to treasure the blessings and the failures in life, because at least you’re here to fail or succeed, because there are so many who aren’t here any longer.

Daniel Warner (1955 – 1993)

Story & Recording by Mark S. King

It wasn’t easy keeping my composure when I interviewed for my first job for an AIDS agency in 1987. Sitting across from me was Daniel P. Warner, the founder of the first AIDS organization in Los Angeles, LA Shanti. Daniel was achingly beautiful. He had brown eyes as big as serving platters and muscles that fought the confines of the safe sex t-shirt he was wearing.

I’m Mark S. King, a longtime HIV survivor.

At 26 years old, with my red hair and freckles that had not yet faded, I wasn’t used to having conversations with the kind of gorgeous man you might spy across a gay bar and wonder plaintively what it might be like to have him as a friend. But Daniel did his best to put me at ease. He hired me as his assistant on the spot, and then spent the next few years teaching me the true meaning of community service.

As time went on, Shanti grew enormously but Daniel’s health faltered. He eventually made the decision to move to San Francisco to retire, but we all knew what that really meant. I was resigned to never see him again.

In 1993, Shanti hosted our biggest, most star-studded fundraiser we had ever produced. It was a tribute to the recently departed entertainer Peter Allen, lost to AIDS, and the magnitude of celebrities who came to perform or pay their respects was like nothing I have ever seen. By that time, I had become our director of public relations, and it was my job to corral the stars into the media room for interviews.

Celebrities like Lily Tomlin, Barry Manilow, Lypsinka, Ann-Margret, Bruce Vilanch, and AIDS icon Michael Callen were making their way through the gauntlet of cameras to the crowded media room. And then one of my volunteers approached me with a look of shock and excitement on his face. He pulled me from the doorway.

“I didn’t know he was going to be here,” he said with wide eyes. “I mean –“

“Who?” I asked. Oh my God. Tom Hanks? Richard Gere?

“He’s with Miss America, Mark,” he said. “They’re right behind me.”

We both turned as the couple rounded the corner of the hallway. They entered the light of the media room and I barely kept a gasp from escaping.

Beautiful Leanza Cornett, who had been crowned Miss America, in part, by being the first winner to have HIV prevention as her platform, had a very small man at her side. His head bore the inflated effects of chemotherapy, which had apparently done little to stem the lesions that were horribly visible across his face, his neck, his hands. His eyes were swollen nearly shut. In defiance of all this, his lips were parted in a pearly, shining smile that matched the one worn by his gorgeous escort.

I stepped into the media room, wanting to collect myself, to wipe the look of pity off my face. I swallowed hard and stepped into the doorway to announce them to the press.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” I said. “Miss America 1993 Leanza Cornett, escorted by Mr. Daniel Warner, co-founder of the Los Angeles Shanti Foundation.”

“Ladies and gentlemen,” I said. “Miss America 1993 Leanza Cornett, escorted by Mr. Daniel Warner, co-founder of the Los Angeles Shanti Foundation.”

The couple walked into the bright light and several flashes went off at once. And then the condition of Miss America’s companion dawned on the camera crews. A few flashes continued, slowly, like a strobe light, and across the room a few of the photographers lifted their eyes from their equipment to be sure their lenses had not deceived them.

Daniel looked to me with a graceful smile, and it became a full, sunny grin as he looked to the beauty queen beside him and put his arm around her. She pulled him closer to her. Their faces sparkled and beamed – glorious, joyful, defiant – in the blazing light of the room.

That man, I thought to myself, that brave, incredible man is the biggest star I have ever seen.

And then the pace of the flashes began to grow as the photographers realized they were witnessing something profound. The couple walked the path through the room and toward the other door.

“Just one more, Mr. Warner?” one suddenly called out.

“Miss America! Just another?”

The room became a cacophony of fluttering lenses and calls to look this way and that, all of it powered by two incandescent smiles.

Daniel and Leanza held tight to each other, their delight lifted another notch as they basked in their final call. Every moment of grace, every example of bravery and resilience I have known from people living with HIV, can be summed up in that glorious instant of joy and empowerment.

“Boss,” I said to him as they exited the room, “I didn’t know you would be here. It’s just… so great.”

He winked at me.

“I’ll be around,” he said. “I brought my whole family with me tonight. I need to get to the party and show off my new girlfriend!”

The three of us laughed, and then I watched Daniel and Miss America, arm in arm, disappear down the hall and into the reception.

Only months later, I received a phone call.

“Mark, this is Daniel,” said a weakened voice. “Monday is my birthday, and I thought that might be a good day to leave.”

Daniel had always been fiercely supportive of the right of the terminally ill to die with dignity and on their own terms. We shared some of our favorite memories of our days at Shanti, and I was able to thank him for his faith in me and setting into motion a lifetime of work devoted to those of us living with HIV.

Daniel P. Warner, as promised, died on his birthday on Monday, June 14, 1993. He was 38 years old.

* * * * *

This story is an edited version of the essay “The Night Miss America Met the Biggest Star in the World,” which Mark S. King published in March 2015 on his website, My Fabulous Disease. Photo credit: Leanza Cornett and Daniel Warner by Karen Ocamb.