Stories of Caregiving

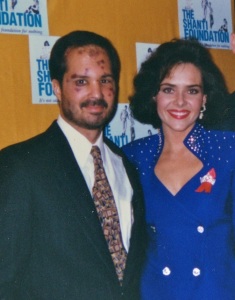

Dr. Anthony Fauci, AIDS Researcher and Champion

Recording by Peter Staley (pictured left of Dr. Fauci)

Story by Irwin Rappaport & Peter Staley

Photo provided by Peter Staley

If you’re like most Americans, you probably first learned about Dr. Anthony Fauci in connection with COVID-19 when he served on the Trump White House Coronavirus Task Force. Fauci later served as Chief Medical Officer under the Biden Administration, until he left government at the end of 2022.

His tenure working with Trump was filled with controversy with the President, other Republican politicians, and the right-wing media and its followers. This was not Tony Fauci’s first brush with controversy, however. For over three decades, Fauci was at the center of public and private battles over public health research and policy.

In 1984, Tony was at the forefront of US scientific research for HIV and AIDS medication as the new Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAD).

I’m Peter Staley. I first met Tony Fauci in 1989 at the International AIDS Conference in Montreal where the AIDS activist group I was a member of, ACT UP, rushed and took control of the stage during the opening session and disrupted various scientific presentations. We demanded faster access to experimental AIDS drugs.

Fauci was familiar with ACT UP by then. He had been quietly meeting with ACT UP members for the prior two years. The AIDS epidemic was killing thousands of our friends and loved ones in America each year and infecting many thousands more. On top of facing death, fear and homophobia in the 1980s and the first half of the ‘90s, those of us with HIV or AIDS had to confront the sky-high cost of approved AIDS drugs, and the slow drug trial and approval process.

We were denied access to experimental drugs. As patients, we were excluded from advocating for ourselves during the process of researching and developing drugs. ACT UP was fed up.

We blocked New York City streets during rush hour. We seized control of the FDA building and stormed the campus of the National Institutes of Health where Fauci worked. We stopped trading on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange. We disrupted Mass at St. Patrick’s Cathedral. We covered anti-gay Senator Jesse Helms’ house with a giant inflatable condom. ACT UP co-founder Larry Kramer called Fauci a murderer in an essay in the Village Voice.

Yet as controversial and critical as we were, Dr. Fauci sat down with us, even inviting us to frequent dinners at the home of his deputy. Days after our takeover of the AIDS conference in Montreal, we met with Dr. Fauci to hammer out details of a new program that expanded public access to experimental drugs. As I was led away in handcuffs after climbing the portico at the NIAD building where I was tackled by police, Tony spotted me and asked me if I was OK.

He cared enough about us and those we spoke for to listen to us, both our criticism and our suggestions. That led to a new policy where patients affected by HIV and AIDS, and all other diseases thereafter, were given a seat at the table to advocate for themselves and those like them during the scientific research process.

He was the driving force in designing President George W. Bush’s game-changing policy called the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), which has saved over 25 million lives worldwide. Perhaps Tony’s empathy, dedication to science, and willingness to persevere in the face of relentless criticism were strengthened because, outside of public view, he cared for hundreds of AIDS patients participating in clinical trials at the NIH hospital during the 1980s and early ‘90s, and continued to do rounds there until he left government at the end of 2020.

As I wrote in a guest essay in The New York Times on Fauci’s final day in government service:

“We draw hope from the progress of science. We are blessed with heroes willing to stand up for truth, unbowed by withering assaults. On behalf of all of us, thank you, Tony Fauci.”

Jaime Jesus Jimenez, 1963-1995

Story & Recording by Guy Berube

Jaime Jesus Jimenez (May 18, 1963 – October 27, 1995). That’s us in 1990, Jaime in front, in Little Rickie’s photo-booth, madly in love.

I had just ‘landed’ in New York in 1989 — illegally — and got a gig as bouncer and bar back at The Bar, an infamous queer hangout in the East Village where some scenes of “Cruising” where shot with Al Pacino. I met Jaime on my first shift. It was instant, our connection.

Jamie was the first to make a move on me. That fuckin smile did it.

“Hey Babe, when do you get off work?” he says.

“Wait in line, Buttercup,” I replied.

That ride lasted five crazy years. Jaime was the only man I ever fell in love with. He was insanely beautiful, inside and out. The stories are endless but one that I cannot erase is bathing Jamie at his weakest in the last stages of his illness. That very moment, looking at each other, knowing this was it. I felt something shift in my chest. It was my heart literally aching.

Fuck I miss him.

Rev. Dr. Stephen Pieters: Survivor & Trailblazer

(1952-2023)

Recording (2022) by Jessica Chastain

Story by Irwin M. Rappaport

The Rev. Dr. A. Stephen Pieters is an AIDS survivor, an AIDS activist and a pastor who ministered to people with AIDS from the earliest years of the AIDS epidemic. Steve received his Master of Divinity Degree from McCormick Theological Seminary in 1979 and became pastor of the Metropolitan Community Church in Hartford, Connecticut.

In 1982, Steve resigned his position as pastor in Hartford and moved to Los Angeles. A series of severe illnesses in 1982 and 1983 eventually led to a diagnosis in 1984 of AIDS, Kaposi’s Sarcoma and stage four lymphoma. One doctor predicted he would not survive to see 1985.

And yet, 1985 proved to be a watershed year for Rev. Pieters. He became “patient number 1” on suramin, the first anti-viral drug trial for HIV which led to a complete remission of his lymphoma and Kaposi’s sarcoma. Unfortunately, suramin was found to be extremely toxic, and it came close to killing him twice.

Also in 1985, during his suramin treatments, he appeared via satellite as a guest on Tammy Faye Bakker’s talk show, Tammy’s House Party, on the Bakkers’ PTL Christian network. Tammy Faye took a huge risk with her evangelical Christian audience by inviting Pieters on the program and advocating for compassion and love for gay people and people with AIDS.

I’m Jessica Chastain, and portraying Tammy Faye in her interview with Rev. Steve Pieters was one of the highlights of my role in the 2021 film The Eyes of Tammy Faye. The interview was done via satellite because of fears that the PTL crew would not be comfortable with an in-person interview.

Steve told People magazine that: “She wanted to be the first televangelist to interview a gay man with AIDS. It was a very scary time and there was still a lot of fear about AIDS and about being around a person with AIDS. And I thought the opportunity to reach an audience that I would never otherwise reach was too valuable to pass by. I’ve had people come up to me in restaurants and tell me, ‘That interview saved my life. My mother always had PTL on, and I was 12 when I heard your interview, and I suddenly knew that I could be gay and Christian, and I didn’t have to kill myself.'”

Tammy Faye’s support for people with AIDS and the gay and lesbian community continued. Bringing

along her two children, she visited AIDS hospices and hospitals, went to LGBT-friendly churches, and

participated in gay pride parades.

When the Bakkers’ PTL network and Christian amusement park were embroiled in scandal and she became the subject of jokes and Saturday Night Live skits, she said in her last interview, “When we lost everything, it was the gay people that came to my rescue, and I will always love them for that.”

Tammy Faye passed away from cancer in 2007, but Rev. Pieters continues to thrive both personally and professionally. He has served on numerous boards, councils, and task forces related to AIDS and

ministering to those with AIDS, and his series of articles about living with AIDS was collected into the

book I’m Still Dancing. For many years, Pieters served as a chaplain at the Chris Brownlie Hospice,

where he discovered a gift for helping people heal into their deaths.

Pieters was one of twelve invited guests at the first AIDS Prayer Breakfast at the White House with U.S. President Bill Clinton, Vice President Al Gore, and the National AIDS Policy Coordinator in connection with World AIDS Day 1993, and President Clinton spoke about Rev. Pieters in his World AIDS Day speech on December 1, 1993.

Pieters has been a featured speaker for AIDS Project Los Angeles and his story is told in the

books Surviving AIDS by Michael Callen, Voices That Care by Neal Hitchens, and Don’t Be Afraid Anymore by Rev. Troy D. Perry. He has received many awards for his ministry in the AIDS crisis from

church organizations, the Stonewall Democratic Club in Los Angeles, and the West Hollywood City

Council.

In 2019, his work in AIDS Ministry, including his Tammy Faye Bakker interview, became part of the LGBT collection in the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. Pieters left his position with UFMCC AIDS Ministry in 1997, earned a masters’ degree in clinical psychology, and worked as a psychotherapist at Alternatives, an LGBT drug and alcohol treatment center in Glendale, California.

Now retired, Pieters is busier than ever with speaking engagements, interviews, and finishing up his memoir. He has been a proud, singing member of the Gay Men’s Chorus of Los Angeles since 1994.

* * * * *

Steve Pieters passed away on July 8, 2023, at age 70. Pieters’ memoir, Love is Greater than AIDS: A Memoir of Survival, Healing, and Hope, was published posthumously in April 2024.

Rev. Bernárd Lynch: A Priest on Trial

Story & Recording by Cosgrove Norstadt

Photo © Life Through a Lens Photography

With so many tributes to loved ones who fell victim to HIV and AIDS, I want to pay tribute to one man who has devoted his life to caring for those with HIV and AIDS. This one person has made such a positive impact on the LGBTQIA community and has literally ministered to thousands of men who were alone and lost. This man is Reverend Bernárd Lynch.

During the AIDS crisis of the 1980s and ‘90s, Bernárd was a tireless voice in the New York City community and traversed the difficult road of illness and death. His leadership served as a beacon of light to those of us lost in the sea of dying faces we could not save. Bernárd took up a fight of which many other men shied away. This man used every ounce of his being to provide care to those who died and to those of us living and blindsided by AIDS. Bernárd’s faith in God never wavered.

Bernárd is an out and proud Roman Catholic priest who has marched in the Gay Pride parades of New York and London for the past 30 years. He has touched the hearts of gay men and lesbian women from the shores of the United States to England to his homeland of Ireland. Few men living can be called icons, but I certainly would call Bernárd an icon.

Bernárd’s list of accomplishments is long and varied. He has worked for the betterment of the LGBT community worldwide.

Father Lynch first came to notice in New York City in 1982 when he formed the first AIDS ministry in New York City with the Catholic group Dignity. It was this same year that he was drafted to work with the then-New York City Mayor Koch’s Task Force on AIDS.

In 1984, Father Lynch publicly backed Executive Order 50 in New York, which forbade discrimination from employers who did business with the city or received business funding. At the height of the AIDS pandemic in 1986, he used his voice to publicly speak up against Cardinal O’Connor in New York City Council chambers for Intro 2, that guaranteed lesbian and gay New Yorkers the right to work and housing without prejudice against their sexual orientation.

Accusations of sexual abuse were lodged against Rev. Lynch in a criminal case in 1989, in which

he was found not guilty and acquitted. Some, including Rev. Lynch, believe that the prosecution

was part of a smear campaign against him by Cardinal O’Connor and his allies in the church and

government. A 2019 civil lawsuit against the Catholic Archdiocese of New York, in which Rev.

Lynch was accused of sexual abuse, was dismissed for lack of evidence.

His work related to HIV and AIDS and his persecution in New York were profiled by Channel 4 in

three documentaries: AIDS: A Priest’s Testament, Soul Survivor, and Priest on Trial. He

received the AIDS National Interfaith Network Award for Outstanding Contribution to HIV and AIDS

Ministries in 1990. In 1992, Father Lynch was the first priest of any denomination to march in

London’s LGBT parade dressed as a priest. In 1993, he founded a support group for priests who

are gay.

His autobiography, A Priest on Trial, was published in 1993. In 1996, the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence canonized Father Lynch outside Westminster Cathedral in London. In 2006, Father Lynch became the first legally married and legally valid priest in the world to have a civil partnership with his partner and husband, Billy Desmond.

In 1986, he received the Magnus Hirschfeld Award for outstanding services to the cause of Irish LGBT freedom. Father Lynch was welcomed in 1995 to the Palace of the President of Ireland by her Excellency President Mary Robinson.

Never in my life have I met, or been privileged to know, a man who represents the LGBT community so well.

Bearing Witness to Transformation

Story & Recording by Ed Wolf

I met a young gay man on the AIDS Unit at San Francisco General Hospital when I worked there in the ’80s.

He had just been diagnosed with Kaposi’s sarcoma lesions in his lungs and was told he had a short time to live. The medical team contacted his parents, who lived far away, and they came immediately. During a five-minute meeting with the doctor, they found out their son was dying and also that he was gay. When I met the father, he told me it was harder for him to find out his son was a “fag” than to hear that he would be dead soon.

It took almost three weeks for their son to die. Every day, his parents watched as the nurses — primarily lesbians and gay men, some with AIDS themselves — continued to care for him, clean him and lessen his pain as much as possible.

I was there the morning he died. When the father stepped out of the room and saw me, he hugged me and cried and cried and cried. He was as tall as me, and his grief was so vast. I remember thinking we were both going to fall down. He kept saying his boy was gone.

The next day, the parents returned to say good-bye. They thanked everyone for their love and care of their son. The mom took me aside and said she was going to miss me. She said, smiling, that she and her husband had talked and wished they could adopt me and bring me home with them.

I kept in touch with them for a while. They started a support group for parents of children with AIDS in their community.

Daniel Warner (1955 – 1993)

Story & Recording by Mark S. King

It wasn’t easy keeping my composure when I interviewed for my first job for an AIDS agency in 1987. Sitting across from me was Daniel P. Warner, the founder of the first AIDS organization in Los Angeles, LA Shanti. Daniel was achingly beautiful. He had brown eyes as big as serving platters and muscles that fought the confines of the safe sex t-shirt he was wearing.

I’m Mark S. King, a longtime HIV survivor.

At 26 years old, with my red hair and freckles that had not yet faded, I wasn’t used to having conversations with the kind of gorgeous man you might spy across a gay bar and wonder plaintively what it might be like to have him as a friend. But Daniel did his best to put me at ease. He hired me as his assistant on the spot, and then spent the next few years teaching me the true meaning of community service.

As time went on, Shanti grew enormously but Daniel’s health faltered. He eventually made the decision to move to San Francisco to retire, but we all knew what that really meant. I was resigned to never see him again.

In 1993, Shanti hosted our biggest, most star-studded fundraiser we had ever produced. It was a tribute to the recently departed entertainer Peter Allen, lost to AIDS, and the magnitude of celebrities who came to perform or pay their respects was like nothing I have ever seen. By that time, I had become our director of public relations, and it was my job to corral the stars into the media room for interviews.

Celebrities like Lily Tomlin, Barry Manilow, Lypsinka, Ann-Margret, Bruce Vilanch, and AIDS icon Michael Callen were making their way through the gauntlet of cameras to the crowded media room. And then one of my volunteers approached me with a look of shock and excitement on his face. He pulled me from the doorway.

“I didn’t know he was going to be here,” he said with wide eyes. “I mean –“

“Who?” I asked. Oh my God. Tom Hanks? Richard Gere?

“He’s with Miss America, Mark,” he said. “They’re right behind me.”

We both turned as the couple rounded the corner of the hallway. They entered the light of the media room and I barely kept a gasp from escaping.

Beautiful Leanza Cornett, who had been crowned Miss America, in part, by being the first winner to have HIV prevention as her platform, had a very small man at her side. His head bore the inflated effects of chemotherapy, which had apparently done little to stem the lesions that were horribly visible across his face, his neck, his hands. His eyes were swollen nearly shut. In defiance of all this, his lips were parted in a pearly, shining smile that matched the one worn by his gorgeous escort.

I stepped into the media room, wanting to collect myself, to wipe the look of pity off my face. I swallowed hard and stepped into the doorway to announce them to the press.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” I said. “Miss America 1993 Leanza Cornett, escorted by Mr. Daniel Warner, co-founder of the Los Angeles Shanti Foundation.”

“Ladies and gentlemen,” I said. “Miss America 1993 Leanza Cornett, escorted by Mr. Daniel Warner, co-founder of the Los Angeles Shanti Foundation.”

The couple walked into the bright light and several flashes went off at once. And then the condition of Miss America’s companion dawned on the camera crews. A few flashes continued, slowly, like a strobe light, and across the room a few of the photographers lifted their eyes from their equipment to be sure their lenses had not deceived them.

Daniel looked to me with a graceful smile, and it became a full, sunny grin as he looked to the beauty queen beside him and put his arm around her. She pulled him closer to her. Their faces sparkled and beamed – glorious, joyful, defiant – in the blazing light of the room.

That man, I thought to myself, that brave, incredible man is the biggest star I have ever seen.

And then the pace of the flashes began to grow as the photographers realized they were witnessing something profound. The couple walked the path through the room and toward the other door.

“Just one more, Mr. Warner?” one suddenly called out.

“Miss America! Just another?”

The room became a cacophony of fluttering lenses and calls to look this way and that, all of it powered by two incandescent smiles.

Daniel and Leanza held tight to each other, their delight lifted another notch as they basked in their final call. Every moment of grace, every example of bravery and resilience I have known from people living with HIV, can be summed up in that glorious instant of joy and empowerment.

“Boss,” I said to him as they exited the room, “I didn’t know you would be here. It’s just… so great.”

He winked at me.

“I’ll be around,” he said. “I brought my whole family with me tonight. I need to get to the party and show off my new girlfriend!”

The three of us laughed, and then I watched Daniel and Miss America, arm in arm, disappear down the hall and into the reception.

Only months later, I received a phone call.

“Mark, this is Daniel,” said a weakened voice. “Monday is my birthday, and I thought that might be a good day to leave.”

Daniel had always been fiercely supportive of the right of the terminally ill to die with dignity and on their own terms. We shared some of our favorite memories of our days at Shanti, and I was able to thank him for his faith in me and setting into motion a lifetime of work devoted to those of us living with HIV.

Daniel P. Warner, as promised, died on his birthday on Monday, June 14, 1993. He was 38 years old.

* * * * *

This story is an edited version of the essay “The Night Miss America Met the Biggest Star in the World,” which Mark S. King published in March 2015 on his website, My Fabulous Disease. Photo credit: Leanza Cornett and Daniel Warner by Karen Ocamb.

A Life Shaped by HIV/AIDS

Story & Recording by Louis Buchhold

My name is Louis Buchhold, and I live in West Hollywood, California. My entire adult life has been shaped by HIV and the AIDS crisis. It has done things to me and for me I would have never chosen had I not been gay and HIV positive.

The early talk about a mysterious gay disease didn’t scare me. I was young and horny and full of wanderlust. I was one of those beautiful young men you may have encountered on Santa Monica Boulevard, a runaway from the Midwest, in a life resembling a John Rechy novel.

Before my young adulthood bloomed, I took a wild ride through a world that soon came apart around us. The generation of free love I grew up in had turned to free death. I watched everyone in my life fall to the disease and die.

I was a lucky one. I only had minor and treatable opportunistic infections.

I became an art director at Liberation Publications and oversaw the national bi-weekly magazine, The Advocate. It was a hot time for everyone trying to get the latest information about AIDS, what the government was doing or not doing about the epidemic, about support services, about hate crimes, and details on organizations like ACT UP and how they were making the world aware of what was happening to us.

I vividly recall the growing AIDS quilt photos and stories I laid out – probably the only information small-town gays saw. I felt I had an important function to our community at that time, and it pushed me forward.

At a point the terror on the streets was deafening, and things became so grim. Funerals and wakes were turned into parties set up by the deceased only weeks or days before their death, and strictly intended to be fun memories of and for our friends and lovers. It was too much to think about the corroded decimated shells the disease left behind.

One good friend, Wade, had been a clown, a very sensitive and happy man who believed in the power of laughter and loved nothing more than to make people smile, volunteering his time all over LA. He was a son of fame, born in LA privilege – the privileged family who threw him out, disowned him and left him to the streets, where he was eaten from the inside out by Candida, an opportunistic infection. It was a ghastly way to go. He went through it without family, in County Hospital, only loved by us AIDS outcasts. It was better for his high-profile parents if he died forgotten.

A week after Wade’s ugly demise, all his friends met at his memorial margarita party he arranged. I was loaded. I was so loaded in those days just to make it through. It took a lot to hold back my fear and hatred and agony from all the loss and death. I stood in front of Wade’s photo with my margarita, surrounded by his adoring friends, my friends. I fell apart at the seams, crashed onto my knees and couldn’t catch my breath.

How could such a thing happen to such a beautiful man? How could the world allow, or even sanction, the death of my entire generation of gay men?

All my friends were dead or dying. My youth was stolen. I couldn’t hold onto it. I saw my future: like so many of my kind, I would meet my end alone on the street.

Someone lifted me up and took me home, and the daily drinking continued without a pause. The world hurt too much. Eventually I received my diagnosis and death date, summer of 1997. And like others before me, I tried to drink myself away before the unthinkable happened. Unfortunately, I appear to have pickled myself instead – and wasn’t able to die. I only preserved eternal pain and woke up one day laying in the street in Cathedral City at 40.

Similar to Wade’s memorial, a man pulled me up and drove me to AA. It is there I re-started my life, having mostly no fond memories of my youth. But my health struggle didn’t stop with cleaning up. In 2008, I came home from the hospital to die from complications of HIV/AIDS. I didn’t want to die alone trapped in a hospital bed. I wasn’t expected to live past that week. Miraculously, I lived, my work apparently not completed.

I’m 22 years sober today and over 17 years undetectable on medication. I’m a psychologist in Counseling Psychology, and a licensed Marriage and Family Therapist. I work in rehabilitative counseling and recovery.

AIDS Project Los Angeles: A Typical Day

Story & Recording by Stephen Bennett

Hello, my name is Stephen Bennett, and I was Chief Executive Officer of AIDS Project Los Angeles in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, which was a very dark period as there was no hope, there was no treatment for people with HIV, and there was so much fear in the world and fear in our community. And hate. And it was a really tough time.

APLA began with an information hotline, and just emergency basic health for people who found out they were sick. It expanded quickly into a food bank, case management, buddy programs, public education and a very sophisticated hotline system.

I want to tell you a story about a morning at work that gives you a slice of what life was like. So, it was early on in the morning, and I was going to work. Our building — the windows were shot out — meaning warnings — and graffiti was put on the wall saying, “We hate faggots,” “You deserve to die.” All kinds of really vulgar and ugly things. And we really didn’t want our clients coming to their place of safety and refuge to see it.

So, we put a Teflon paint on the building and we put bulletproof windows in, and every morning we had a company come and power wash the building. So I went early, because I wanted to make sure that the building was cleaned and looking good and the contractors were doing what they were supposed to be doing.

So I got there, and as I was about to enter the building — there was a little alcove for the front door was – and lying there was a young man, a 16-year-old, and his clothes were torn and he was asleep.

And I said, “Hey, you got to get up, you got to get moving.”

And he woke up and said, “I don’t know where to go. I don’t know who to talk to.”

But he told me he lived outside of Lincoln, Nebraska, and he had come home from school, told his mother he was gay.

She said, “No, you’re not. You cannot be. Go to your room, and don’t tell your father.”

He heard his father come in. His mother and father argued. His father came up to the room and beat him and beat him and beat him. And threw him out the second-floor window. He fell to the ground, he passed out, and he woke up a number of hours later. He walked to the farm nearby, got $100, hitchhiked into Lincoln, and took the bus from Lincoln to downtown Los Angeles.

He then arrived at three o’clock in the morning and walked the seven miles from downtown to the AIDS Project building on Romaine, and curled up on the front door, hoping to be found.

He said that he didn’t know anybody that was gay, but he had read in People magazine about the AIDS Project’s Commitment to Life event, and he knew there had to be gay people there, and he was hoping somebody gay would find him and rescue him. That was the world we were living in.

So, I took him over to the Gay and Lesbian Center. There was a lesbian at the desk who was just fantastic, and she hugged him and told him that they had a place for him.

While this was happening, one of our client’s mother was trying to reach him at home, and she hadn’t been able to reach him for two or three days. And so she went over to see him, and early in the morning, she was quite concerned – he had been very ill, very sick.

And she knocked on the door. Nobody answered. She unlocked it, she came in and found her son. He had taken a gun and blown his brains out. And they were splattered all over. The place was a mess.

Of course, she was very torn up. She didn’t know what to do, so she called his case manager at AIDS Project – Bill, one of our best case managers.

He went immediately and tried to comfort her and figure out what they were going to do. During that time, emergency workers wouldn’t care for us when we were injured, and mortuaries wouldn’t have us in their mortuaries. So they were dealing with that.

At the same time, out in Simi Valley, which is about an hour and a half from here, a young man got up, he was living with his sister, he was quite sick. He lost his home, he had lost his job. He was living there with his sister, and his sister was pretty tired of it.

And she told him, “You get on a bus, you go to APLA to their food bank, and you come back and you bring something home with you. You bring some food back.”

He took the bus from Simi Valley into — over the hill into Granada Hills, and then another bus to Studio City, and then another bus over the mountain into Hollywood, down to our building on Romaine. Well, you can imagine what this was like for somebody who was feeling just terrible.

So he gets to our offices. We had a volunteer there, an older woman who was like our mother, and she would take the kids — the men — when they came into the building and hug them and wrap them in a blanket to keep them warm.

He got very sick while he was waiting in the lobby. They had to take him to the bathroom and change his clothes and wrap him up. There he lay, waiting for his case manager to come in, and his case manager didn’t show up and didn’t show up and didn’t show up. And he felt so lost.

Well, his case manager was at the apartment with the mother and her son who had killed himself, and he had been trying to find a mortuary that would come and get the body, and he couldn’t find one. And finally, they found some guy in Sylmar that if they paid in cash, he would come get the body, but they had to have everything wrapped up in big double-plastic black bags.

The guy said, “I won’t touch this body. I won’t have anything to do with this body.”

And so they were putting the body in these bags, and so they were waiting for the mortuary to come. Finally, the case manager comes to the office and sees his client laying there on one of our couches in the lobby, sobbing. He picks up the client in his arms. The client was very sick, had lost lots of weight, was pretty light – and he carried him to his office to sit him down and talk to him. And when he kicked open his office door, the door squeaked.

After this kind of morning, Bill had had it. This was the last straw, and he totally flipped out. I’m upstairs in my office, Bill comes into my office. He starts screaming and knocking stuff off my desk, and very upset.

And I said, “What in the hell is going on with you?”

And he said, “My door squeaks.”

I came around the desk, gave him a hug, and we went downstairs to the supply room, and I got some WD40, and we went to his office. He told me the entire story of his day. The day went forward.

I spent the day in staff meetings, talking about testing, talking about when we’re going to see a treatment. And then I went to cocktail parties and dinner to raise money. And that was a day in the life of one of our case managers and for me, the CEO of the AIDS Project, at the height of the AIDS epidemic.

Jim Brumbaugh, 1948-1991

Story & Recording by Ellen Matzer

One of the bravest men and patients I remember. They were all brave, but Jim Brumbaugh (1948-1991) faced this illness with a calm and realism we didn’t see often.

He was in and out of the hospital many times. He had a multitude of opportunistic infections throughout the year he was ill. He had a wonderfully supportive partner and family that was also rare back then.

I remember one of the times, Jim knew he was close to the end. I went into see him. He was sorting out Imperial Topaz gemstones. I had never heard of that stone before, and he explained to me that it was one of the most beautiful topaz stones there was. He was sorting out the stones to give them to all his nieces after he passed.

I remember sitting with this wasted yet handsome man, looking at each stone and talking to his partner about which family member should get which stone. It was as if Jim was having a normal conversation about anything. I remember thinking, how can he do this so matter-of-factly? His partner had also known that my 2-year-old son liked elephants. The next day, he came in with a bandana that had elephants on it. I still have it.

Jim, I miss our talks. I miss you, how brave you faced every speed bump, every obstacle. There were so many we lost back then. I try to remember everyone’s face, something special about them. Most of them, I do.

Valery Hughes and I wrote the book Nurses on the Inside, Stories of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in New York City to remember this generation lost. To warn against it happening again.

We must know the history of the awful epidemic. There are too many people that don’t remember, were too young or not even born yet. It was a holocaust. We must honor all these brave men and women. We must never forget they were here.

— Ellen Matzer, RN

In Remembrance of Those Who Were Alone

Story & Recording by Cosgrove Norstadt

In 1981, I was living in Ohio and dating a man from New York City. Because of him, I became aware of a strange cancer striking gay men in New York and San Francisco. Unfortunately, in Ohio, no one was worried about AIDS because only people in NYC and San Francisco were at risk.

Four years later, I moved to NYC. I met the Reverend Bernard Lynch who was ministering to those afflicted with AIDS. I ask him how I could help. What could a naive youth from Ohio know about such a massive Holocaust? I wasn’t cut out for ACT UP and criticized for my lack of anger and outrage. I wasn’t angry. I was sad. Terribly sad. I was sad for all the men dying alone in the hospitals.

Bernard directed me to St. Clare’s Hospital to volunteer. They wanted me to wear masks and gloves and footies, but I couldn’t. If I was going to hold you in my arms as you died, I was going to let you touch me, cough phlem on me and cry on my shoulder. From a Christ-like point of of view, I could not do less than Christ himself.

Most men at St. Clare’s lasted two weeks, tops. I hadn’t lived in NYC long enough to make friends. My friends became short term and very deep with the men who were alone and dying. I met sex workers who taught me compassion. I met intravenous drug users who taught me to be accepting. Every two weeks, I lost my newest best friend. All of these men shared their most intimate secrets with me and, most of all, their love.

The number of men I held as they died is impossible to calculate, but as my life continues, I remember the patients of St. Clare’s Hospital. I remember how you were ostracized by friends and family. I remember how, as gay brothers, we loved one another unconditionally.

This is my tribute to those who were alone. They had no friends and no family. I was just a 22-year-old boy from Ohio, learning life lessons I wish never existed. I miss all of you, and I continue to remember you and love you.

Baby Aaron

Story & Recording by Raymond Black

In the late 1980s and early 90s, I worked with an organization that placed volunteers in hospitals and group homes to work with children with HIV and AIDS.

I met Aaron when he was nine months old and cared for him until he died at the age of 18 months. This photograph was taken on his first and only birthday.

The women who were full-time caregivers at the home used to call me Aaron’s father because of our bond. Both his parents had already died. The women used to say he seemed jealous if he saw me holding another child.

Aaron was very sick. His lungs filled constantly with mucus. I was often asked to gently pat him on the back while he was given medication through a nebulizer. I could tell how much stress it caused his tiny body. Seeing him suffer was not easy.

When I spoke, Aaron would put his little hand against my jaw as if he was feeling the words as they formed in my mouth. On Aaron’s first birthday, I brought him some presents, and we had a little party on the ward. He was healthier than he had ever been before. He didn’t need to remain attached to tubes. I was told I could take him up to the rooftop garden.

I walked Aaron around the garden, holding him like I am in this photo. Just him and I, alone outside under a beautiful blue sky. An airplane flew overhead, and he looked up. I told him about airplanes. I showed him flowers, rubbed them against his cheek so he could feel them. I just kept talking to him. He held my jaw as I spoke the entire time, feeling the words as they formed.

When Aaron died months later, the women at the home told me that was the only day of his life that he went outside other than for trips to the hospital. Aaron was moved to a hospital for his last few days and placed in an oxygen tent. I went every day after work. While I was not present when he died late one night, I leaned in under the tent whenever I was there and never stopped talking to him.

Aaron was one of the reasons that I joined ACT UP. His memory fueled my activism.

Today, Aaron would be 30 years old. We lost so much in this epidemic. So much suffering. So much death of those far too young to die.

“Entertaining Angels”

Story and Recording by Sue Scheibler

Photo courtesy of Sue Scheibler

I’m recording this story on April 13, 2023 — 31 years to the day since my dear friend Terry died in my arms.

He had just turned 33. We had been friends since college, working at Disneyland together through our college years and for a few years after that, before he moved away. We reconnected in 1990 when he found me at Disneyland and told me he had AIDS. I told him I was there for him, with him, no matter what, committed to being a caregiver in whatever way he would need. And so I was, through the many doctor’s visits, transfusions, and hospitals over the next two years.

Until spring 1992, when it became clear that living with AIDS was moving slowly towards dying from AIDS. Yet, as we all know, it was so hard to give in to the reality and make the hard decision about whether to take him off the drugs. By this time, he was bedridden, blind, and suffering from dementia, yet still always Terry with a quick laugh, a smile that still lights up my life as I remember it.

During this time, we had developed the habit of lying in bed together, Terry wrapped in my arms, chatting quietly. Our chats usually started with his question: “Do you know where I was last night?” and my answer: “No, where?”, opening the door to yet another marvelous journey together into his imagination.

On this day, he said, “I went to a convention of angels. I couldn’t go to the Crystal Cathedral where the big ones were. I went to the Episcopal Church down the street. Even so, the angels were incredible!”

“And what happened,” I asked.

“Well, the whole idea was to teach me how to be an angel. They let me try on wings.”

“I bet you looked great. You have the legs for it.”

He giggled and replied, “Well, I felt great. But I don’t think I can learn to play the harp. Anyway, I asked them if I can come back and be your guardian angel.”

“And what did they say?”

“Yes, but there is a two-year apprentice program where we learn to be angels. After that, I will be able to come back and be your guardian angel.”

We lay there together for a while, talking about angels until he dozed off. I went out to where the rest of our little community of caregivers were chatting.

“I think Terry has let me know it’s time to let him go. He’s ready.”

Two weeks later, Terry passed peacefully in my arms, surrounded by friends. We all swore we felt his spirit touch each of us on our heads as he died.

Two years later, I felt his spirit so powerfully next to me, heard his laugh in my ear. I heard the echo of his laugh in mine, the light of his smile in mine as I smiled through my tears and finished doing my dishes.

Richard Lawrence Reed, 1956-1995

Story by Michael Martin

Read by Rick Watts

I’m Rick Watts, a member of the West Hollywood Disabilities Advisory Board, and I’m reading Michael Martin’s story about his late partner, Richard.

_ _ _ _ _

Richard Lawrence Reed (February 28, 1956 – November 11, 1995) was a beautiful soul, a kind man and my first partner. We met serendipitously. It was August 1984, and I was supposed to be meeting a co-worker, but the plans fell through, and I decided to go to another local bar.

As my favorite song of the moment — “My Heart’s Divided” by Shannon — started playing, I boldly walked up to a man near the dance floor and asked him if he would dance with me. He agreed, and we became inseparable from that moment on for over 11 years.

I had just turned 19 and was smitten with this lovely man nine years my senior. Like most relationships, ours evolved and deepened after the initial stages of attraction, sex and lust. We become true lovers and friends and began to build a life for ourselves. Neither of us were rich or highly educated, but we were employed and did alright.

Well, within a short period of time, Rick started saying he didn’t feel quite right. It was never anything serious — a cold or a flu — and he would recuperate quickly. At the same time, we were just beginning to hear about the new mysterious “gay illness,” and he decided he wanted to get tested. We tested together sometime in mid-1985, and Rick tested positive and I tested negative.

Our relationship was still in its infancy and there seemed no way it could be true, but it was. Rick learned what information was available and soon had a specialist doctor — the only one in the area.

There was never any question in my mind about leaving the man I loved because of a test result or its ramifications. At that moment, Rick was healthy and we were happy. Love doesn’t end based on a test result.

For a while Rick’s health was fine and he was simply monitored. We proceeded with life as normal, with the exception of keeping his status a secret. Times were different then, and there was so much misunderstanding, stigma and ignorance.

Slowly, Rick’s health deteriorated but not in the usual manner associated with AIDS. He never contracted pneumonia or Kaposi’s sarcoma. It began with thrush and a gradual decline in his T-cell counts. There was only one medication available — AZT — and Rick was put on it, but its side effects only made him feel worse.

Rick also decided to tell his parents about his status and illness. He was close to them and things were becoming more evident. I, however, told no one — not my family, co-workers, supervisors or friends. Gradually, due to the stigma surrounding the disease and our own fear, we withdrew from friends we knew would never understand or accept it. Outside of a few close friends, we were isolated, but we made our life as pleasant and normal as we could.

Well, Rick deteriorated both physically and mentally. It was gradual, painful and unstoppable. In early 1995 on what was to be our last trip together, Rick became rapidly disoriented and argumentative. There had been signs of dementia prior to this, but this was a sudden onslaught. I cut the vacation short, and we headed home. Rick was hospitalized upon our return and given what treatments were available, but they helped very little. He was exhausted, his spirit was depleted, and he was tired of fighting. We returned home and the hospice took over. He gave up on living, but never on us.

Rick died in my arms around 5:00 a.m. on November 11, 1995.

Later, I would find notes Rick wrote to me when he knew the dementia was taking hold and he might not be able to say what he wanted to say. He made a scrapbook of memories of us filled with love notes, cards, an odd memento, or just a written note of special moments of our life and love. He left me a book of writings, drawings, stories and poems he had worked on over the years.

Although my world was forever changed and my heart ripped apart, the most important thing he left me was a feeling of love. Never-ending love.

AIDS in Prison, and My Lost Brothers

Story & Recording by Richard Rivera

My name is Richard Rivera, and I remember how devastating AIDS was in the New York State prison system. It was much worse than the public realizes or would imagine.

All around me during the early 1980s, prisoners began to experience sudden weight loss, sores in their mouth, a persistent cough, and other inexplicable medical problems. Popping up on the news were rumors of “that gay disease.” Its official name was Gay-Related Immune Deficiency, or GRID. But no one really knew what was going on or how it was transmitted. All we knew was that this new thing was a death sentence.

Ironically, despite our fears and superstitions, prisoners continued to do what prisoners did. Intravenous drug use, tattooing, and high-risk sexual behavior remained the norm.

In 1985, concerned over a friend named David who had disappeared from general population, I convinced one of the nicer officers to sneak me into the infirmary for a visit. When the doors opened, I saw a dorm-like area with beds neatly made with hospital corners lining the wall like a military barrack. But the room and the beds were empty.

The officer pointed to the back of the room, which was much darker. I made my way to an area sealed off with Plexiglas. It had an additional eight beds, on which eight prisoners lay: some on their backs, others in tight little balls. Their eyes were sunken into their skull, their hair thinning; their arms looked like twigs and their fingers were impossibly long. Some of them were covered in sores. One had swollen, purple legs, the skin so tight it looked like ripe fruit. He was softly moaning. It was my friend David.

I met David in 1983 at Great Meadow Correctional Facility, aka “Comstock.” Prisoners called it “Gladiator School,” because of its propensity for violence. I was 17 when I arrived. I couldn’t read or write, and I had no friends and reputation. I got into so many fights that I lost count after the fifth month there.

It was after a particularly violent encounter that I met David. He took me under his wing, showing me who to avoid and what not to do, while encouraging me to wear my glasses and stop eating my fingernails. I had no more trouble at Comstock. But David had a history of intravenous drug use and, I suspected, continued using and sharing needles.

In 1984, I was transferred to Green Haven Correctional Facility, and David followed soon after. He arrived smaller, thinner, and not at all the strong, robust, confident man I remembered. Then a few months later, David was transferred. That’s when I heard rumors of the secret ward and went looking for him.

The conditions in that ward were deplorable. Porters almost never went in to clean, medical staff rarely visited, and officers refused to have any contact with them at all. There were no medications, with the exception of the over-the-counter stuff like cough syrup and Motrin. AZT was still years away.

But every week from 1985 to 1987, I went there to care for David and the other men. David’s condition worsened, and ultimately, he was transferred to St. Agnes Hospital in White Plains, where he died.

The reason I am here today is because of brothers like David — and Jamel and Mongo and Joe and Pierre and Larry — who cared for me, corrected me, encouraged me, nudged me along the way. I went looking for David in that ward, because men like him had saved me, too, from being broken.